The secret colonies of graffiti artists and skateboarders

- Published

There's a furore around a graffiti-festooned, skater hangout under threat on London's Southbank. These graffiti and skating "colonies" are all over the UK.

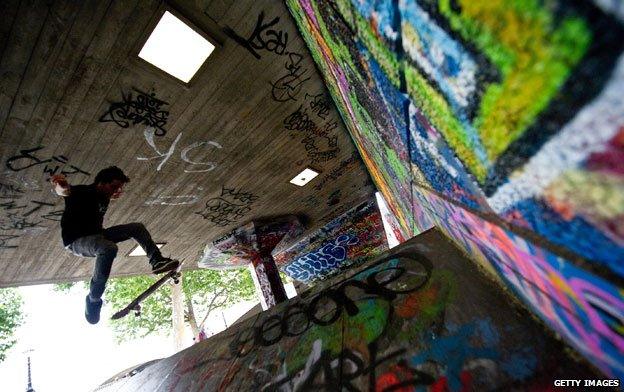

Saunter past the Southbank Centre on a Saturday, and there's always a buzz at the "undercroft".

The spot isn't a designated skate or graffiti park, but one that has grown organically since it was discovered by skateboarders in the 1970s.

Skateboarders see it as their spiritual home. Graffiti artists love the sheltered space.

Elsewhere there is often a zero-tolerance approach to what many see as anti-social behaviour - graffiti on someone else's property is usually criminal damage and skating is often discouraged because of potential danger to bystanders. But the Southbank's concrete area is, broadly speaking, a tolerated space.

Spectators can often be found by the spot - soaking up the activity as an urban, modern-day arts foil to the high culture in the centre.

Now, the centre wants to redevelop the site into retail units and relocate the park. Skateboarders are unhappy, and want to register it as a community space under laws designed to protect village greens.

The tension isn't unique. This type of unplanned, anarchic urban free-for-all is actually pretty common in the UK. But not everybody likes that.

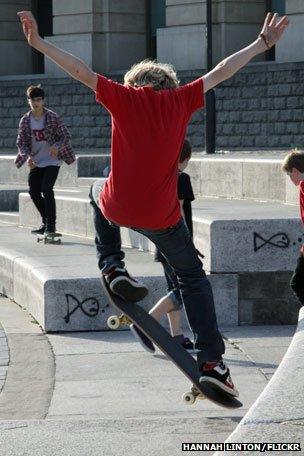

Bristo Square in Edinburgh, which is part of Edinburgh University, is supposed to be an open space for students to congregate and contemplate.

But if you have lunch there, you'll have to ignore the rattle of skateboard wheels.

Skaters are drawn by the smooth surfaces, steps, blocks and benches.

"It was the best place to go in the 1980s and 1990s. Now the city has a skate park too, which is great, but the older guys still love Bristo square - it's got history and is a suntrap," says Ali Menzies, chairman of Skateboard Scotland.

Bristo Square, Edinburgh

The university says it takes a "common sense approach" to the activity, with "reasonable behaviours" likely to be tolerated when rules and regulations prohibiting it are sometimes difficult to enforce.

There's a similar skateboarder haven in Bristol, known as Lloyds, according to Justin Sydenham, co-owner of skate store Fifty Fifty.

"It's a world renowned spot right in the centre of town - it's got three big stair sets and is like an amphitheatre.

Skateboarding in Bristol

"There's quite a big skater scene in Bristol, but we get kids travelling from Wiltshire, Devon and Gloucester because it's such a good, natural spot," he says.

There was once a time when a council's response to a wave of anti-social behaviour was to propose a skate park with some half-pipes and perhaps even a little bit of supervision.

But these free-for-all zones are about something else.

Many skaters and graffiti artists want to do their thing somewhere that isn't officially endorsed, somewhere they chose and built themselves.

"Skateboarding is about exploring, conquering and documenting new terrain, it's about pushing the boundaries about what you can physically do on a board, and the best sites are often a beautiful accident," says Henry Edwards-Wood, 25, a skateboard film-maker who is campaigning for the Southbank site to stay put.

It's a similar thing with graffiti - a practice which sprang up in New York ghettos - according to Bryce Davies, who runs a professional graffiti arts organisation and started a legal graffiti wall at the back of industrial units at Hailey Park, in Cardiff, 12 years ago.

"Graffiti artists are really good at taking over spots society has forgotten about - it could be a place that's in a transitional period between being used by a company and being knocked down, an old abandoned factory or an old quarry - and reacting to the environment.

Hailey Park, Cardiff

"It's completely different in a manufactured park or on canvas - these public spots are being used for creative spaces because of their architectural uniqueness," he says.

These often-derelict places where graffiti flourishes all tell a story.

Competing designs are continuously written over each in an endless loop of spray and counterspray. A cartoon Rottweiler is covered up by a single jagged word, which in turn gives way to a grimacing Christopher Walken.

In other spots, a tag, or name, is written in as many places, as many times as possible, over and over again.

As with skateboarding hotspots, some sites gain more acceptance than others.

In Bristol, the whole of Nelson Street is dedicated to what is claimed to be the UK's largest permanent street art project. There's even an annual festival called SeeNoEvil.

Bristol's SeeNoEvil festival

In Nottingham, graffiti artists get away with painting in a children's play area, so long as they only go when the children aren't there - and they don't paint anything grotesque or violent.

But those that stand the test of time tend to be a well-kept secret and, or, hidden from the public eye, according to Matt Neville, editor of graffiti magazine Wordplay.

"A site, better known as a 'Hall of Fame', is for most a safe area to paint - somewhere the writer won't be hassled by the police or public unless they actually have a genuine interest in the movement.

"The trouble with these areas is, a lot of the time, development takes them over - they are often knocked down to make way for housing, offices or something equally as ugly to the eye," he says.

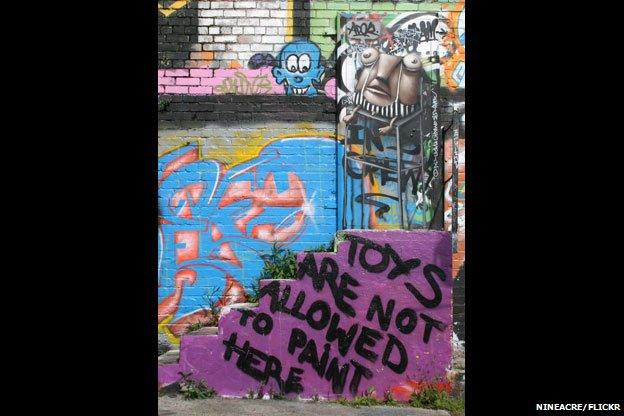

Some of the current spots that exist in Manchester have been snapped by Flickr user nineacre, who describes himself as an interested observer.

He says there are about five accepted sites in the Manchester and Salford area, the most visible of which is known as the Graffiti Palace - a warehouse on an industrial estate on the Manchester Ship canal.

The site has come under threat in the past, and was due to be destroyed as part of the council's riverside re-development plans in 2011. But according to nineacre, it's recently undergone a revival.

"The Graffiti Palace owners have repeatedly resisted appeals to cover the graffiti, which has featured pieces from artists from as far as France, and the Ukraine. The site has spread from one large warehouse, to a half mile section of the canal that it is on," he says.

Salford's 'Graffiti Palace'

A remote sewage pumping station, underpasses and an old garage in the city are also magnets for artists from across Britain.

But he says sites come and go due to the transient nature of the art form, and the people involved in it.

"[The subculture] can be secretive - with artists wanting to be known, and at the same time anonymous - and the permission sites can sometimes disappear with people changing their mind after a while," he says.

Some people will always think graffiti is an ugly and unwelcome eyesore, which fundamentally breaks the law. Sites that spring up are often scrubbed away by council or company crackdowns.

Campaigners who want the Southbank's undercroft to stay in its 40-year-old site say the issue is one of historical significance and respect.

"Just because this is a counter culture, it doesn't make it any less legitimate.

"It would be like knocking down a 100-year-old clock tower in the middle of a village and replacing it," says Davies.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external