Almost human: Lab treats trauma with virtual therapy

- Published

Ellie is a creation of ICT, and could serve as an important diagnostic and therapeutic tool for veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The University of Southern California's Institute for Creative Technologies is leading the way in creating virtual humans. The result may produce real help for those in need.

The virtual therapist sits in a big armchair, shuffling slightly and blinking naturally, apparently waiting for me to get comfortable in front of the screen.

"Hi, I'm Ellie," she says. "Thanks for coming in today."

She laughs when I say I find her a little bit creepy, and then goes straight into questions about where I'm from and where I studied.

"I'm not a therapist, but I'm here to learn about people and would love to learn about you," she asks. "Is that OK?"

Ellie's voice is soft and calming, and as her questions grow more and more personal I quickly slip into answering as if there were a real person in the room rather than a computer-generated image.

"How are you at controlling your temper?" she probes. "When did you last get into an argument?"

With every answer I'm being watched and studied in minute detail by a simple gaming sensor and a webcam.

How I smile, which direction I look, the tone of my voice, and my body language are all being precisely recorded and analysed by the computer system, which then tells Ellie how best to interact with me.

"Wizard of Oz mode" is how researcher Louis-Philippe Morency describes this experiment at the University of Southern California's Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT).

In the next room his team of two are controlling what Ellie says, changing her voice and body language to get the most out of me.

Real people come in to answer Ellie's questions every day as part of the research, and the computer is gradually learning how to react in every situation.

It is being taught how to be human, and to respond as a doctor would to the patients' cues.

Soon Ellie will be able to go it alone. That opens up a huge opportunity for remote therapy sessions online using the knowledge of some of the world's top psychologists.

But Dr Morency doesn't like the expression "virtual shrink", and doesn't think this method will replace flesh-and-blood practitioners.

"We see it more as being an assistant for the clinician in the same way you take a blood sample which is analysed in a lab and the results sent back to the doctor," he said.

The system is designed to assess signs of depression or post-traumatic stress, particularly useful among soldiers and veterans.

"We're looking for an emotional response, or perhaps even any lack of emotional response," he says.

"Now we have an objective way to measure people's behaviour, so hopefully this can be used for a more precise diagnosis."

The software allows a doctor to follow a patient's progress over time. It objectively and scientifically compares sessions.

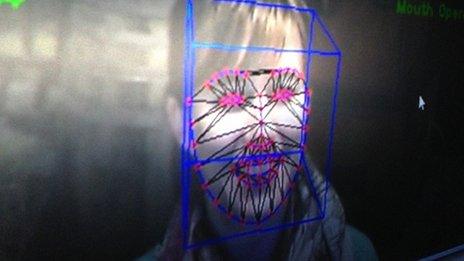

Researchers diagram the minute movements of the human face to create more realistic computer models

"The problem we have, particularly with the current crisis in mental health in the military, is that we don't have enough well trained providers to handle the problem," says Skip Rizzo, the associate director for medical virtual reality at the ICT.

"This is not a replacement for a live provider, but it might be a stop-gap that helps to direct a person towards the kind of care they might need."

The centre does a lot of work with the US military, which after long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has to deal with hundreds of thousands of troops and veterans suffering from various levels of post-traumatic stress disorder.

"We have an issue in the military with stigma and a lot of times people feel hesitant talking about their problems," he says. A virtual counselling tool can alleviate some of this reluctance.

Alastair Leithead sat down with a computer program designed to mimic a therapist. Despite an awkward first encounter, he grows more comfortable.

"We see this as a way for service members or veterans to talk openly and explore their issues."

The whole lab is running experiments with virtual humans. To do so, it blends a range of technologies and disciplines such as movement sensing and facial recognition.

Dr Morency has won awards for his work into the relationship between psychology and minute physical movements in the face.

"People who are anxious fidget with their hands more, and people who are distressed often have a shorter smile with less intensity. People who are depressed are looking away a lot more," he says.

The researchers analyse the data to make their computer models more accurate

Making computer-generated images appear human isn't easy, but if believable they can be powerful tools for teaching and learning. To that end, the lab is involved in several different projects to test the limits and potential of virtual interactions.

In the lab's demonstration space a virtual soldier sits behind a desk and responds to a disciplinary scenario as part of officer training.

The team have even built a Wild West style saloon, complete with swinging doors and bar.

Full-size characters appear on three projection screens and interact with a real person walking in, automatically responding to questions and asking their own to play out a fictional scenario.

Downstairs, experiments are creating 3D holograms of a human face.

Throughout the building, the work done is starting to blur the lines between the real world and the virtual world.

And the result just may be real help for humans who need it.