Viewpoint: What do radical Islamists actually believe in?

- Published

In the aftermath of the Woolwich attack in which a British soldier was killed, apparently at the hands of Islamist fundamentalists, Quilliam Foundation researcher Dr Usama Hasan argues that moderates must do more to win over Muslim youth.

For decades in the UK and abroad, Muslim discourse has been dominated by fundamentalism and Islamism.

I spent two decades, starting in my teens, as an activist promoting these narrow and superficial misinterpretations of Islam in the UK, along with thousands of others here and millions in Muslim-majority countries, until deeper and wider experiences of faith and life helped me out of these intellectual and spiritual wastelands.

These discourses need to be defeated, and the developing counter-narratives to these worldviews and mindsets need to be strengthened.

By fundamentalism, I mean the reading of scripture out of context with no reference to history or a holistic view of the world.

Specific examples of literalist, fundamentalist readings that still dominate Muslim attitudes worldwide are manifested in the resistance to progress in human rights, gender-equality and democratic socio-political reforms that are too-often heard from socially-conservative Muslims.

The universal verses of the Koran (eg 49:13, "O humanity! We have created you from male and female and made you nations and tribes so that you may know each other: the most honoured of you with God are those most God-conscious: truly, God is Knowing, Wise") promote full human equality and leave no place for slavery, misogyny, xenophobia or racism.

However, other Koranic verses that may seem to accommodate slavery, discrimination against non-Muslims and women and even wife-beating (eg 4:34) were clearly specific for their time and always meant as temporary measures in a process of liberation.

Islam exalted the status of women and slaves in 7th Century Arabia. Ahistorical, fundamentalist readings treat these specific stages as universal and obstinately refuse any progress, effectively insisting on a return to 7th Century values for all societies at all times.

Islamism is often described as "political Islam". A more accurate description would be "over-politicised, fundamentalist Islam", since believers have every right to build their politics on basic religious ideals such as truth, justice and the welfare of all people.

The following may be regarded as the major components of Islamism: Umma, Khilafa, Sharia and Jihad - all of which have become excessively politicised.

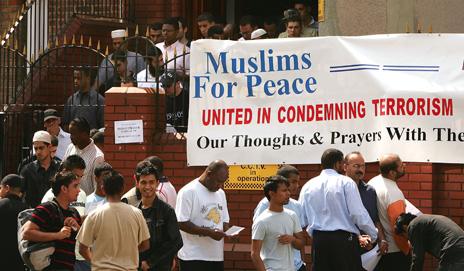

Friday prayers after the 2005 Tube and bus bombings

Umma (nation) translates for Islamists into an obsession with the "Muslim people" and its imagined suffering worldwide (the blessings are never counted, only the problems) that in turn becomes a firmly entrenched victimhood and perpetual sense of grievance.

Conflicts involving Muslims with others are continually cited - Palestine, Kashmir, Afghanistan and Iraq - while ignoring savage internecine Muslim conflicts, such as the Iran-Iraq war or the current wars in Darfur and Syria, or the appalling persecution of Christians in many Muslim-majority countries such as Egypt, Iran and Pakistan.

Khilafa (caliphate) for Islamists is the idea that they are duty bound to establish "Islamic states" - described by vague, theoretical, idealistic platitudes - that would then be united in a global, pan-Islamic state or "new caliphate".

Sharia (law) for Islamists is the idea that they are duty-bound to implement and enforce medieval Islamic jurisprudence in their modern "Islamic state".

Hence the obsession with enforcing the veiling of women, discriminating against women and non-Muslims and implementing penal codes that include amputations, floggings, beheadings and stonings to death, all seen as a sacred, God-given duty that cannot be changed.

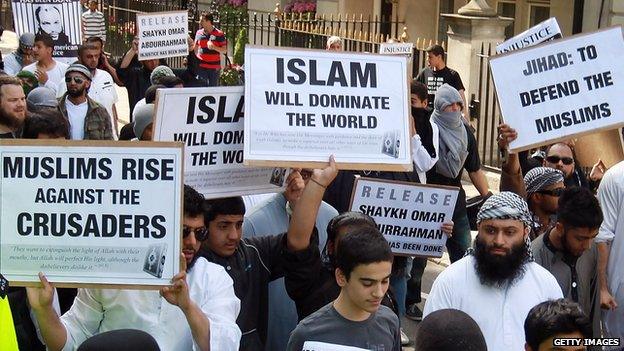

Anjem Choudary said he encountered one of the suspects at a number of Islamist demonstrations

Jihad (sacred struggle) for Islamists is an obsession with violence, whether of a military, paramilitary or terrorist nature. Their Jihad aims to protect and expand the Islamic state. Extremists even dream of conquering the whole world for Islamism by militarily defeating the US, Europe, Israel, India, China and Russia.

Counter-narratives to the Islamist narrative may be developed.

The Koranic references to Umma include the historical aspect, such as the prophets of other faiths and their followers, a strong, interfaith and spiritual notion.

In early Islam, Umma also referred to political communities that included Jews and Christians, such as Medina under the Prophet Muhammad. The Ottomans abandoned the legal pluralism of the "millet" system (a faith-community framework) in the 19th Century and adopted a citizenship model that granted equal rights to all, irrespective of religion.

The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, articulated the same vision for his new Muslim-majority state with Hindu, Sikh and Christian minorities, but these developments have been forgotten under the avalanche of fundamentalist Islamism over the past half-century.

Sharia has had dozens of schools and interpretations over the centuries.

Narrow approaches do not work in our modern world. The holistic approach to Sharia known as Maqasid al-Sharia (universal objectives of law) posits equality, justice and compassion as the basis of all law, and is the only way forward.

The work of the recent or contemporary scholars Ibn Ashur, Nasr Abu Zayd and Ibn Bayyah are crucial in this regard.

It has to be recognised that Koranic penal codes, always accompanied by exhortations to mercy and forgiveness, were often suspended or replaced by imprisonment or financial penalties in the early centuries of Islam, since punishment, deterrence, restorative justice and rehabilitation were the operative concerns.

Also, arbitrary interpretations of Sharia were not enforced at state level in early Islam and most of Sharia is voluntary, relating to believers' daily worship and social transactions.

The Koranic spirit of freedom, equality, justice and compassion must be reclaimed, with an emphasis on Sharia as ethics rather than rigid ritualism.

The Koranic notion of Jihad is essentially about the sacred and physical-spiritual nature of life's struggles, as summed up by "strive in God", a verse revealed in the pacifist period of Islam before war was permitted.

The Arab Spring demonstrated how reform can come from the grass roots

In our times, we need non-violent Jihads; social struggles against all forms of inequality and oppression, and for justice and liberation.

Socio-political Jihads are needed to achieve the goals of noble causes such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that may be seen as an extension of the themes of equality contained in the Prophet Muhammad's farewell sermon.

The military aspects of Jihad are covered by the ethics of warfare. The voluminous Geneva Conventions are in keeping with the spirit of the Koran, which also has a strong pacifist message.

Role-models for such counter-narratives include the many Muslim social reformers of the past century, such as Jinnah's sister Fatima, who is still an inspiration to millions of Pakistani women, and the many Muslim activists who contributed to the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

More recently, the youth of the Arab spring, with an instinctive Islamic, Christian or humanist love of freedom and justice, have broken through the impasse maintained by dictatorships and their subservient clergy.

Such counter-extremist, reform movements must be led at the grass-roots by community and intellectual activists.

Democratic government has a role, but a healthy civil society is best-equipped to resist tyrannical dictatorship, whether religious or secular.

We have much to do, but where there is faith, there is much hope.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external