Where did the hen party explosion come from?

- Published

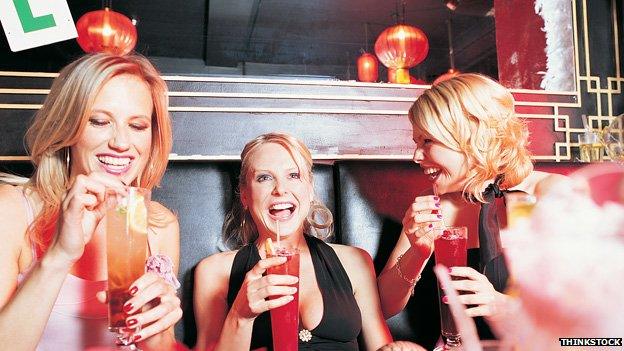

Hundreds of thousands of women will be celebrating their friends' last days of freedom in the wedding season this year. Where did it all start?

The hen night/party/weekend is now massive.

Visit a northern city. Or Brighton or Bournemouth. Count the number of groups wearing themed T-shirts or led by an L-plated bride sliding slowly into inebriation.

For £175, you could buy a city break all inclusive package deal to Amsterdam, pay around two months' worth of gas and electricity bills or drink at least 58 pints of lager. You could also spend a weekend in a country cottage in Bath with 10 women you barely know, celebrating your friend's last days of singledom.

The stags and hen phenomenon is said to be growing despite the economic downturn. According to statistics gathered by hen and stag travel company Redseven, the industry is worth around £275m annually.

In 2012, the average spend on a hen party was £110.

The roots of the hen party tradition in the UK go back further than in the US, says American sociologist Beth Montemurro. There, it is more of a recent phenomenon starting in the 1970s and 1980s as an expression of sexual freedom tied to the sexual revolution of the 1960s.

"In the US, they are clearly modelled on the bachelor party and women wanted to do what they perceived men to be doing, feeling they deserved to be doing something that was more fun," Montemurro says.

Folklorist George Monger wrote about the pre-wedding traditions prevalent in industry in 1971, with some obvious parallels to the hen party culture we see today.

He described the tricks played on female industrial workers on their last day of work. These traditions had been established in the pre-contraceptive pill era, when women were widely expected to leave paid employment upon entering into marriage. The bride would be dressed up in a coat or veil and made to look like a parody of a bride, then paraded around the factory where people would congratulate her.

Sheila Young, a researcher studying the tradition of hen parties in the UK at the University of Aberdeen, says there was a lack of knowledge about sex, with the bride-to-be going from living with her family to becoming sexually active.

As a result, she says, messages with sexual innuendos were tied onto the bride's coat before she was paraded around the local pub - an extraordinary sight by the social standards of the times.

Montemurro, who wrote a book in 2006 on the symbolism of bachelorette parties in the US, says the industry has completely changed since she started her research in the late 1990s.

An industry has grown around hen activities, such as life drawing

Back then, organised hen travel companies and hen club nights didn't really exist, but now it is the industry that is driving the trend.

"Reality TV shows contribute to the belief that it's normal to spend lots of money on bachelorette parties, with women feeling entitled to have everything and spend as much as they want, from the time of engagement to the time of the wedding," says Montemurro.

But this can also lead to friendship breakdowns, she adds, citing examples of women she interviewed who viewed the bride differently - and for the worse - after going through the wedding process.

"Some women changed their opinions of the bride because of the way she dealt with them - she didn't seem as compassionate as they would have expected."

The phrase "hen party" dates back to the 1800s to denote a gathering of females, but there was no pre-wedding context.

Google's N-gram tool, which visualises the rise and fall of keywords and phrases across five million books, is a useful barometer to test the phrase's popularity - it shows a steady increase in the use of the phrase from the mid-1960s onwards.

It was not until 1976 that the Times newspaper first used hen party in the modern-day sense. The term had quotation marks around it - perhaps implying it was still not in common use at that time - and was in a story about a male stripper who was fined by Leicester Crown Court for acting in "a lewd, obscene and disgusting manner".

The concept of sharing a weekend with a group of women you may never have met is another downside, says Kathy Lette, author of Girls' Night Out. She says the experience is akin to "putting oysters with custard".

She describes the social minefield of a trip to Bali where the "posh sisters of the groom" rubbed the bride's friends, including a bridesmaid who has a masters degree in Marxism, up the wrong way.

"Hen weekends sure put the fun into dysfunction," says Lette. "By the end of this sun-drenched sojourn, familial hostilities rivalled two Balkan Republics."

So has the hen culture got out of hand? Lette thinks so, calling for a return "to basics" aka, go for a curry and to the local pub with your nearest and dearest.

Bridal showers are a common tradition in the US, dating back to the 19th Century

"The modern hens weekend is a fairy tale experience all right - scripted by the Brothers Grimm. On the stressometer, psychologists rate planning a wedding as equally traumatic to moving house and bereavement."

One victim of the henflation of recent years is 25-year-old Claire, who had to abandon a hen do in London halfway through because the activities got too expensive.

"Having already eaten at a sushi restaurant, not the cheapest of choices, the bride then decided she wanted to go to an expensive club and I just couldn't afford it," says Claire. "There were three of us who couldn't go and got left behind. The bride told us she was disappointed, which made us feel guilty."

Bridesmaids are frequently left out of pocket after footing all of the upfront costs.

"The cost factor is immense and getting people to commit and pay your money is also a nightmare," says 30-year-old Beth, who organised an afternoon tea party for 15 women in Oxford.

"I was owed about £70 from a girl who never paid up her share of the hotel for two nights, so in the end I had to ask the bride to pay it back. The same girl didn't even come to the wedding."

But throughout her research, Sheila Young interviewed women who told her the most important aspect of a hen party was for it to be fun and an opportunity to bond.

"When it all boils down to it, it's a very intimate gathering and a sign that you're one of the chosen and that's why it's so special."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external