Everest crowds: The world's highest traffic jam

- Published

A "traffic jam" of climbers en route to the summit

Six decades after it was conquered, mountaineers complain that the summit of Mount Everest has become virtually gridlocked with climbers. How did the world's highest mountain become so congested?

In May 1953 Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay stood alone together at the very top of the world.

Nowadays, the same spot is rather less desolate.

Thanks to advances in mountaineering equipment and the indefatigable efforts of Sherpa guides, more climbers than ever are reaching the peak of Mount Everest - a landmark that was once believed to be impossible to surmount.

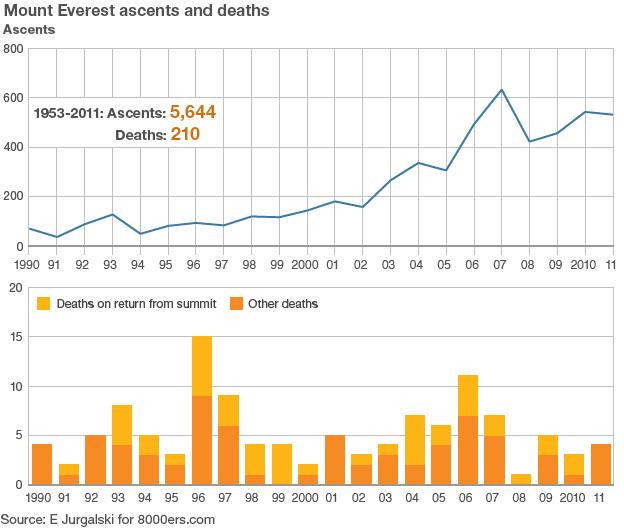

According to National Geographic, external, in 1990 18% of summit attempts were successful. By 2012 that figure stood at 56%.

But this has come at a cost. Critics say the summit has become as congested as a five-lane motorway during bank holiday weekend.

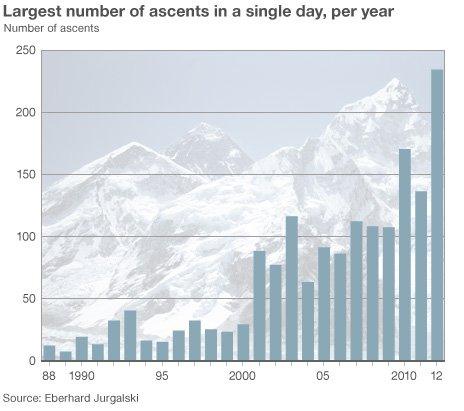

On a single day in 2012, no fewer than 234 climbers reached the peak. By contrast, as recently as 1983 the most successful ascents in a single day was eight, and a decade later that figure stood at 40.

This year some complained, external of waiting two-and-a-half hours in queues at bottlenecks on their way to the summit.

A striking photograph by German mountaineer Ralf Dujmovits, external - which showed a queue hundreds-long snaking its way up during 2012 - ignited a debate about whether the procession was ruining enjoyment of the ascent.

Westerners can pay anything from $10,000 (£6,600) to $100,000 (£66,000) for permits to climb the mountain and guides to accompany them, and a sizeable tourist industry has sprung up around the base - bringing with it complaints about litter and poor sanitation for miles around.

"There were just people everywhere," says Ayisha Jessa, 31, a keen climber from London who recently visited Everest's base camp. At the nearby village of Namachi, she says, "it's completely commercialised - everything is intended for the Western traveller".

For many serious climbers, all this has served to devalue Everest.

"It isn't a wilderness experience - it's a McDonald's experience," says Graham Hoyland, an experienced mountaineer and author of The Last Hours on Everest, an account of the ill-fated 1924 ascent by George Mallory and Andrew Irvine.

Advances in weather forecasting mean climbers time their attempts to the same few days each year, worsening the bottlenecks. A better understanding of altitude sickness has also helped more mountaineers ascend 8,848m (29,029ft) to the summit.

For their financial outlay, Westerners are given a plentiful supply of oxygen and, very often, a Nepalese mountain guide assigned specifically to ensure they get to the top.

The tour parties also ascend using fixed ropes, which help less accomplished climbers but are believed by many elite mountaineers to detract from the sport.

Thanks to all this assistance, more than 3,000 individuals have scaled the mountain since 1953.

They include Californian Jordan Romero, who in 2010 became the youngest person to climb Everest aged 13, and 80-year old Yuichiro Miura from Japan, who set the most recent record for the oldest summiteer. An 81-year-old, Nepalese Min Bahadur Sherchan, is attempting to snatch Miura's title.

"Normally, as long as they are not too ill or too weak, nearly everyone - if they have enough money and patience - can get up Everest," says Eberhard Jurgalski, who has attempted to chronicle every Everest ascent since 1953.

"Also, if the weather hasn't been good for a few weeks it becomes much more crowded on the days you can climb."

Some worry that the influx of inexperienced climbers on to such potentially hazardous terrain could have tragic consequences.

"You have people going up there who don't know how to operate the ropes or use the crampons," says Hoyland. "There's a huge disaster waiting to happen."

In 1996, eight people died within 36 hours near the summit. In 2012, some 10 lives were lost on the mountain, three of them Sherpas.

So it's not surprising that tensions have built up.

According to Hoyland, experienced climbers have grown frustrated that long queues of amateurs using fixed ropes are slowing them down.

Tempers on the mountain boiled over in April when a scuffle broke out at 7,470m (24,500ft) between two well-known European climbers, Ueli Steck and Simone Moro, and a group of Nepalese mountain guides.

While complaints are still made about litter and human waste on the mountain, a series of clean-up expeditions has improved the environmental situation, Hoyland says.

But as Nepalese authorities face calls to take further action, proposals to remedy Everest's congestion have sharply divided climbers.

One expedition company has suggested installing a ladder at the Hillary Step,, external a rocky outcrop just before the summit, where only one person can go up or down at any one time. But purists complain this would lessen the challenge of scaling the mountain.

Mountaineers wait their turn at the Hillary Step

Another proposed solution would be to limit the number of climbers. Until 1985, the Nepalese authorities allowed only one expedition on each route to the summit at any one time, and in theory this practice could be revived.

Others suggest, candidates for a permit could be required to undergo training or at least demonstrate mountaineering experience. "If everyone going up had at least a little bit of an idea about the culture of climbing, that would make a big difference," says Hoyland.

But the notion of imposing quotas sits uneasily with many in the free-spirited world of mountaineering.

Sir Chris Bonington, who reached the summit aged 50 in 1985, says he is grateful that he was there at a time when crowds were restricted.

However, while he believes there is much that can be done to improve Everest's management, he feels uneasy with the idea of denying to others the opportunity he enjoyed.

"If you say there are only 100 or 200 people coming each year, that's a lot of people who will never be able to share the incredible personal experience of getting to the top of the mountain," Sir Chris says.

Restricting the number of visitors would also have a major impact on those who rely on tourism for their income.

"It's a mountain that people live on, and the local community is completely supported by the climbers," says Jessa.

The debate will rumble on. And as long as the memory of Hillary and Norgay's achievement persists, the crowds will keep coming.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published26 May 2012