Why climbers continue to feel Mount Everest's allure

- Published

The world's highest mountain has claimed four more lives but such tragedies make no dent in the increasing number of people attempting its ascent.

The enormously powerful winds that blast Mount Everest relent for just a few weeks every spring.

They are precious weeks that provide climbers with a chance to claim the greatest mountaineering "scalp" of them all - the world's highest summit.

Those wishing to make the ascent must spend months preparing and thousands of dollars for a permit, even before they start.

Then, on the climb itself, they have to brave all that the mountain can throw at them - bad weather, the effects of altitude, even the sight of the corpses of climbers who have died making the attempt.

Four people died on their way down from the summit last weekend.

Two hundred climbers are expected to make an attempt on the mountain this weekend, which is likely to be the last of this year's season.

What is it about Everest that keeps them coming?

"It is really quite simple - it's the biggest mountain in the world."

Dawa Steven Sherpa runs one of the companies that guides climbers on the mountain.

His words echo those of George Mallory, who summed up the allure of Everest before his fatal attempt to climb it in 1924: "Because it's there".

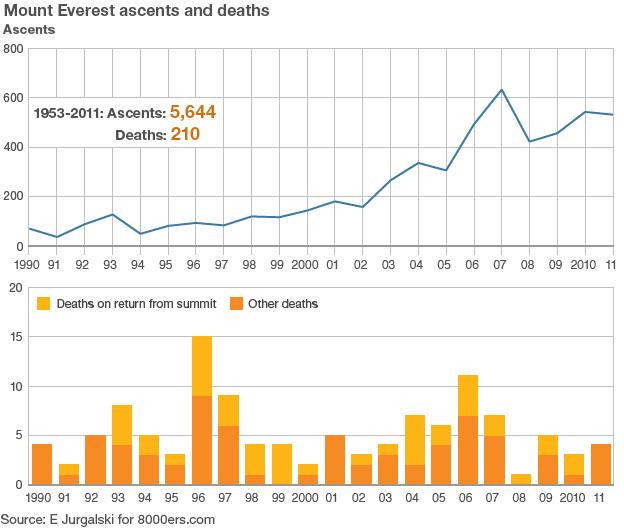

That phrase has been described as the three most famous words in mountaineering, and the challenge proves irresistible to hundreds of climbers every year.

"On the mountain itself, there are around 1,000 climbers at the moment - but it's a big mountain, and if you compare it with Mont Blanc, say, that's not very many", says Dawa Steven Sherpa, speaking to the BBC from Everest Base Camp.

"The problem is everyone wants to go to the summit on the same day at exactly the same time."

That is because climbers are keen to take advantage of perfect weather conditions, which could disappear at any moment and not reappear for months.

On 23 May 2010, for example, 169 climbers reached the summit in a single day - more than the total number who had conquered the mountain in the 30 years following the first ascent in 1953.

The first... Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary

More than 3,000 climbers had reached the summit by the end of the 2010 climbing season.

"We now have more than 50 years' experience of climbing this mountain. We know where to put the ropes, where people should put their feet. It's become a lot easier over the years", says Dawa Steven Sherpa.

And this creates another problem - many of those testing themselves against Everest fail the test.

"I think some people do underestimate it," says Rhys Jones, who in 2006 became the youngest British person to reach the summit.

"There's a price tag on it, and they think, 'why wouldn't I be able to climb it? If I just pay enough, I'll be able to get up it'."

Dawa Steven Sherpa agrees: "Many people do overestimate their abilities. They can be very fit - marathon runners, ultra-marathon runners, iron-man competitors - but they don't understand altitude, and they underestimate the mountain."

For many purist mountaineers, the process of climbing Everest is becoming too commercial, too orchestrated and too reliant on external help.

Reinhold Messner was one of the first people to climb Everest without oxygen, in 1978.

"The route is prepared by hundreds of Sherpas. Extra oxygen is available in all camps, right up to the summit. People will cook for you and lay out your beds. Clients feel safe," he said in a newspaper interview.

But Rhys Jones feels Everest will always be special, and won't ever be "just a treadmill".

"Everyone is aware of the risks", he told the BBC. "They have all read the books, which tend to be about the disasters and the fatalities.

"But actually, risk is part of the attraction - it makes it more of a test, it gives you more to aim for."

- Published22 May 2012

- Published25 May 2012

- Published25 May 2012