How the Coronation kick-started the love of television

- Published

![Composite image showing a family watching TV in the 1950s [image: Getty], with footage from the coronation superimposed on top](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/624/mcs/media/images/67865000/jpg/_67865328_tvcomp.jpg)

The coronation was the first TV event watched by the masses. [Composite image]

Television in the early 50s was basic and still waiting to take off. How did the coronation turn it into the mass medium that shaped our lives?

It was the first event to rattle radio's cage.

The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953 is said to have been watched by more people on television than heard it on "the wireless".

In the UK, nearly eight million people tuned in at home, while 10 million crowded into other people's houses to watch. There were a further 1.5 million viewers in cinemas, halls and pubs.

The number of TV licences shot up from 763,000 in 1951 to 3.2 million in 1954. Many see the coronation as UK television's tipping point.

"I remember people saying 'we've got to get a television set'," recalls cultural historian Robert Hewison, who celebrated his 10th birthday on the day of the coronation.

Sir David Robinson, founder of Radio Rentals, decided to move into TV sets after observing the impact.

As a medium, TV seemed exciting. But the output fitted the dreary image of post-war austerity.

There was just one channel. Broadcasts were limited to a few hours in the afternoon followed by a break before resuming at night. A break in those days meant a blank screen. Commercial television did not arrive until 1955.

Programming ranged from the banal, to the dry, to the niche. Often it was just radio with pictures, says Mark Aldridge, author of the Birth of British Television.

The Tuesday before the coronation, the Times' television schedule amounted to seven lines of one column.

The broadcast began at noon with cricket - Yorkshire v Lancashire - followed by a programme called simply For Women. At 4pm it was Watch with Mother. Cricket returned at 4.15pm before Children's Television at 5pm, followed by a break.

Programming restarted at 8pm with Newsreel, followed by Pattern of Ulster, a guide to life in Northern Ireland introduced by the Viscount Brookeborough. Next was a comedy series, Two of Everything, then Our Concern is the Future, a talk by Christopher Wood. The day's output concluded at 10.20pm with Weather and News (sound only).

But the coronation was special, offering almost a full day of viewing.

Archive: Commentator Mary Hill describes the scene as the crowds watch the Queen arrive for the Coronation

The novelty of the technology should not be overlooked. The first item in the TV schedule read: 9.15-10.15 Tuning Signal - a large chunk of time for viewers to tune their sets.

Hewison vividly remembers the broadcast. "The picture wasn't as impressive as 35mm newsreel in the cinema. It was more grey and brown than black and white. But you were seeing something live."

The weather was appropriately British. He can still remember the troops marching through the rain.

Those controlling the coverage were wary of its impact. At the key moment, when the Queen was anointed with oil, the broadcast looked away tactfully. "The cameras panned up towards the vaults of the abbey so you didn't see that bit," Hewison recalls. It was felt to be of too much religious significance for the watching millions.

US coverage later caused a stir back in the UK by breaking off for an ad break that contained an advert featuring a chimpanzee.

In the UK, there was approval at the decision to televise the ceremony. The next day's Times was almost awestruck.

"At first it was difficult to grasp the fact that what one saw was not a news film but historic events unfolding even as one watched."

TV meant it wasn't just those who lived in London who could watch the event

There was a sense that the world would never be the same. The commoners had been invited in and given a front row seat.

"Yesterday, for the first time in perhaps a thousand years, the Sovereign was crowned in the sight of many thousands of the humblest of her subjects," the Times article continued.

"Yesterday, by penetrating at last, even vicariously, into the solemn mysteriousness of the Abbey scene, multitudes who had hoped merely to see for themselves the splendour and the pomp, found themselves comprehending for the first time the true nature of the occasion."

It was almost shocking, says historian David Kynaston, author of Modernity Britain: Opening the Box, 1957-59.

"Parliament wasn't broadcast, there was a lot of secrecy and very little accountability. But suddenly this new medium could transmit quasi-private events. It was quite a shock."

The coronation gave TV creative momentum and led to other televisual firsts that year, says Aldridge. The Quatermass Experiment started that summer. Unlike the stage plays and book adaptations, here was an original drama - a six part sci-fi series - made specially for TV.

Later that year came an Elizabethan theme night to honour the new Queen. Even the continuity announcers - who were visible to viewers - wore Elizabethan dress. "In one way it appears strange but it was also quite modern to have a theme night," Aldridge says.

The arrival of ITV in 1955 gave TV another spike in popularity. It brought a mainstream appeal that the BBC's "paternalist, Reithian" output lacked, Kynaston says.

ITV soon dominated the viewing figures with quiz shows, such as Double Your Money, that became part of the national conversation.

And it was a classless medium. If anything the working classes were quicker to grasp its appeal, recalls Hewison whose upper middle class family refrained from getting a set. With one in each living room, it replaced the hearth, he argues.

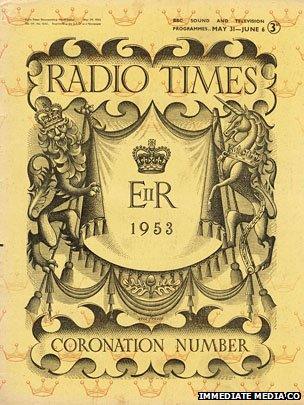

What the coronation achieved as a one-off event was crystallised in 1956 when the Radio Times switched its running order. Television took over at the front of the magazine, while radio was shunted to the back.

"I think of 50s television as being like folk tales," says Hewison. Newspapers were hugely popular then but readers were spread between many different titles. Whereas television was monolithic and unifying. "Everyone shares the same tales on only one or two channels. It really was a mass medium."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external