How Timbuktu's manuscripts were smuggled to safety

- Published

When Islamist rebels set fire to two libraries in Timbuktu earlier this year, many feared the city's treasure trove of ancient manuscripts had been destroyed. But many of the texts had already been removed from the buildings and were at that very moment being smuggled out of the city, under the rebels' noses.

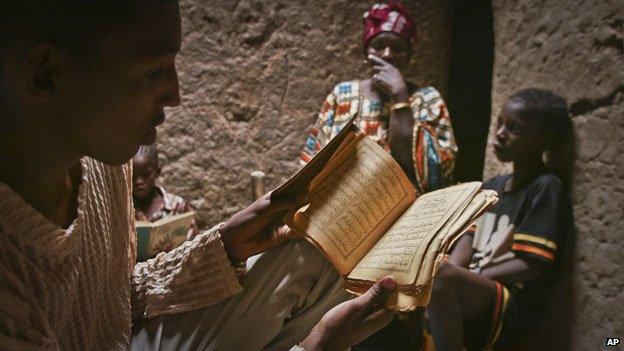

"These manuscripts are really precious to us. They are family heirlooms. Our history, our heritage," says Dr Abdel Kader Haidara, owner of one of Timbuktu's biggest private libraries, containing manuscripts dating back to the 16th Century.

"In our family there have been generations and generations of great scholars, great astronomers, and we have always looked after these documents."

When Islamist rebels took over Timbuktu last year, looking after the documents began to look like an impossible task.

Under their strict interpretation of Islam, the rebels soon began destroying shrines they considered "idolatrous". The documents held in Timbuktu since its glory days as a centre of Islamic learning in the 13th to 17th Centuries were equally vulnerable.

As a precaution, Haidara and other big book-owning families, together with officials of the state-run Ahmed Baba Institute, had already removed most documents from major collections, hiding them in private homes.

After the destruction of the shrines, it became clear a more radical approach was necessary.

"We realised we needed to find another solution to take them entirely out of Timbuktu itself," says Haidara. "It was very difficult. There were loads of manuscripts. We needed thousands of metal boxes and we didn't have the means to get them out. We needed help from outside."

Dr Haidara, who masterminded the rescue, with boxes of manuscripts

With approval from 35 key families, Haidara went in search of funding, which he secured from the Prince Claus Foundation in the Netherlands and the German Foreign Office, among others.

But there was a major problem - the rebels often searched vehicles leaving Timbuktu, and if they found manuscripts they would certainly confiscate or destroy them.

"It was very risky. We evacuated the manuscripts in cars, carts and canoes," says Haidara, who launched the operation in October, frequently concealing the metal boxes under crates of vegetables and fruit.

"One car could only take two or three metal boxes at the most. So we did it little by little."

The cars headed for Bamako, via Mopti, the last government-controlled town in Mali during the Islamist occupation of the North.

The canoes - part of local transport in northern Mali for centuries - travelled to Bamako on the river Niger, via Djenne.

When in January of this year the insurgents torched two libraries belonging to the Ahmed Baba Institute, as they were retreating from Timbuktu, the covert rescue operation was already half-complete - and the libraries themselves had been all but empty for months.

Haidara estimates that only a few hundred manuscripts were destroyed.

As the situation in the north remained volatile, however, the rescue operation continued for three months after the rebel withdrawal, until 2,400 metal boxes containing an estimated 285,000 manuscripts had been delivered to private homes in the capital.

In Bamako, however, the papers now face threats of a different kind.

Having been preserved for centuries in a dry desert climate, they now find themselves in the tropics, with the rainy season about to start.

"The houses are not air-conditioned and in comparison humidity in Bamako is much higher than in Timbuktu," says Dr Michael Hanssler of the Gerda Henkel Foundation, who has just returned from a fact-finding mission to assess the condition of the documents.

It's impossible for air to circulate around the documents as long they are stored in metal containers. Mould usually develops at humidity levels of 60%, and levels as high as 80% are expected in July and August.

Efforts are now under way to renovate a building in Bamako that will have proper storage facilities. Windows are currently being bricked up in order to protect the manuscripts from daylight, insects and heat.

There will also be a workspace where experts can restore the documents and digitise them for scholars worldwide to study.

"The manuscripts of Timbuktu have always been an aspiration for scholars working on the intellectual history of Africa," says Eva Brozowsky, a German paper restoration specialist, who examined six of the chests in Bamako in April.

The 2,000 documents she had access to were from Islamic North and West Africa, but also from the Middle East, and covered commerce and diplomatic relations as well as commentaries on the Koran, jurisprudence and Arabic linguistics.

"This is an untapped treasure trove of unthinkable value, nobody quite knows what's hidden in these chests," adds Hanssler, whose foundation is supporting the restoration efforts financially and logistically.

The manuscripts have never been kept in optimal conditions, Hanssler says.

"Some of the documents have been damaged in the past by insects or water. Others have suffered from being exposed to dry air in Timbuktu, and the leather covers have become brittle and have cracked."

The manuscript paper itself - thought to have originated from the region around Venice in Italy - has aged substantially. As a result the documents have become fragile and fragmented, and some of the writing has faded.

Haidara himself estimates that about 20% of the manuscripts are severely damaged and extremely fragile, while another 20% are damaged, but less severely.

While the security situation in northern Mali remains uncertain the manuscripts should stay in Bamako, he says, but he won't hear of them being taken out of the country.

"The day there is a lasting peace in Timbuktu we will return them to Timbuktu. But until that time comes we must preserve them well - put them in boxes, restore them, catalogue them and digitise them."

When they go back, it won't be in canoes or under piles of vegetables, and hopefully many will be in better condition than when they left.

Dr Abdel Kader Haidara was interviewed on the BBC World Service programme Newshour.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published29 May 2013

- Published28 July 2023