How Islamist militancy threatens Africa

- Published

- comments

With Islamist militant groups across the Sahara region still able to flex their muscles despite the French intervention in Mali, former UN diplomat and security expert Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah considers their threat to Africa.

The countries of North and West Africa have become embroiled in a new war waged by violent Islamist militants - a conflict that has no front line.

Last week's suicide assaults in Niger on a military base and French-run uranium mine, and a siege in January of the gas plant in Algeria reveal the insurgents' ruthless tactics.

And the start of the withdrawal of French troops from Mali, four months after recapturing northern cities from Islamist insurgents, is being touted by the militants on internet forums as the beginning of their victory.

But this is no sudden development.

Militants and armed radical groups have expanded and entrenched their positions throughout the Sahel and Sahara over the last decade under the umbrella of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Mahgreb (AQIM).

They move from one country to another - a hard core of operatives working in an area that covers parts of south-west and south Libya, southern Algeria, northern Niger, north-east Mauritania and most of northern Mali.

Poorly administrated, these vast desert spaces provide the groups with an ideal terrain.

They also have connections in northern Nigeria, especially with home-grown militant group Boko Haram.

Cocaine

Analysts believe there are dormant cells in many large cities, including most capitals in the Sahel region.

There are several reasons that this network of militancy has flourished.

One significant factor is the perceived arrogance and corruption of urban elites.

The marginalisation of poorer communities - both in rural areas and smaller towns - and minority ethnic groups has further alienated them from the governing classes.

Disgruntled young men have been happy to join radical groups that not only offer them an ideology, but money.

And it is the widespread drug trafficking in the region that is believed to have enriched militant groups.

Details about the operations are sketchy - large amounts of money are involved to ensure secrecy and loyalty.

Drugs from South America are taken across Africa to Europe, where they are more profitable and marketable.

A kilogramme of cocaine bought in Latin America for $3,000 (£1,990) can be sold in the capitals of West Africa for about $16,000; in North Africa it sells for $25,000 and can fetch about $45,000 in Europe.

Getting involved in the transit business as the conveyor or security agent provides not only a good salary but also the social recognition that money brings.

This is a tantalising prospect to many unemployed young men.

Western hostage taking is no less profitable for militant groups - and is another "business" that has grown in the last 10 years.

Between 80m-100m euros ($103m-130m) is estimated by the Center for Strategy and Security in the Sahel Sahara to have been paid in ransoms in this time, despite both the United Nations and the African Union discouraging such payments.

Information technology has been a great help to a hard core of between 350 and 450 experienced AQIM fighters estimated to work within the coalition of Islamist militant groups in the Sahel and Sahara region.

Co-operation

The leadership and high ranking officers are mostly Algerians and Mauritanians, but increasingly the Sahelians are moving up the ladder.

They are very mobile and knowledgeable about the region, can often avoid detection and the monitoring of their communications, and can count on hundreds of determined militias and armed sympathisers.

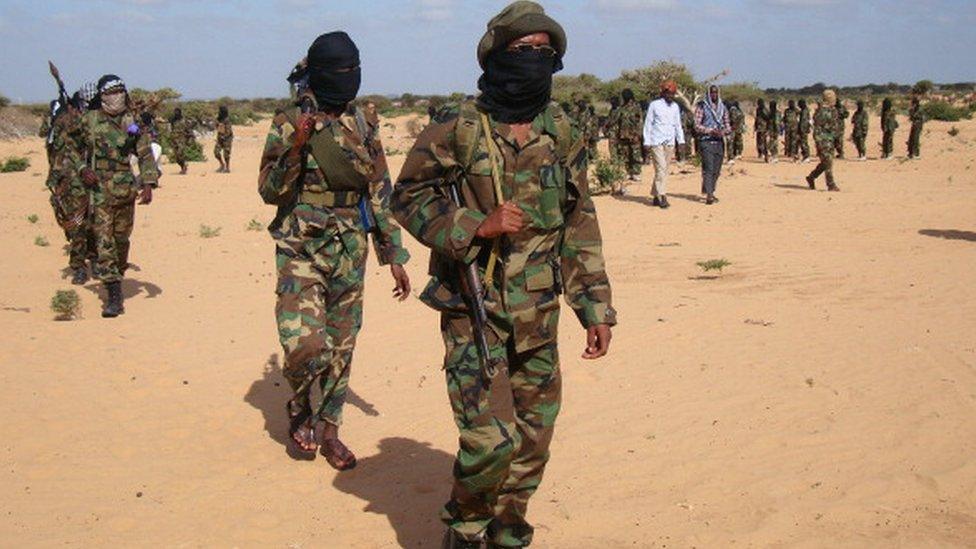

AQIM has its roots in groups in Algeria, Libya and Tunisia. One of its key affiliates is the well-disciplined Mujao group, which was active in Mali and claimed responsibility for last week's Niger attacks.

There is also believed to be a connection between AQIM and the growing piracy of the Gulf of Guinea - similar to the situation in Somalia where the al-Qaeda affiliated al-Shabab group has strong links with pirates operating in the Indian Ocean.

In both cases the main objective is to expand the source of their funding and to enlarge their popular support through redistribution of the loot.

Last summer also saw reports of a liaison between the Islamist militants in the Sahel, al-Shabab and a few other "informal units" operating in the porous borders area between Chad, Libya and Sudan.

Al-Shabab militants were reported to have travelled overland to Mali disguised as Koranic students or merchants.

In Nigeria Boko Haram has managed to buy sophisticated weapons

En route it is believed they stayed in safe houses in major cities before joining groups in the AQIM network to share experiences.

The groups interact on more of an informal than a co-ordinated basis - facilitated by lax border controls and territorial continuity.

They also exploit the tribal systems and relationships between ethnic groups, using them to their advantage.

Most rebel groups' supplies and logistics come down from the Maghreb or the fighters seize them by force from local armies.

Frustrated border populations either help the combatants or fail to report on them to government officials, despite being given Thuraya satellite phones to do so.

Today, however, the Sahel and Sahara region is at a crossroads.

There is an opportunity for the region's governments to get a grip on the situation and take advantage of France's gains.

Improving economies coupled with nascent freedoms in North Africa could also help improve weak governance, a major ingredient of terrorism.

In coalition with the private sector and civil society organisations, they could fight poverty and disenfranchisement, which could help quell the rebellion.

But there is only a short window of opportunity.

Combatants presently fighting on far fronts, such as Syria, may well return - whether victorious or defeated - to boost the morale and numbers of the Saharan radical groups confronted by French troops.

Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah is the former UN envoy for Somalia and West Africa and now runs the Center for Strategy and Security in the Sahel Sahara in Mauritania

- Published21 January 2013

- Published27 February 2013

- Published22 December 2017

- Published15 June 2015

- Published12 March 2013