Do we know whether pornography harms people?

- Published

There are frequent calls for action to be taken over pornography but what is the evidence it harms people who view it?

In 1961, a psychologist called Albert Bandura carried out a groundbreaking experiment. He had children watch an adult beating up an inflatable doll, then left each child with the doll to see what he or she would do. The children also threw punches at it.

He concluded that we are inclined to copy violent behaviour, rather than find it cathartic.

Years later, Neil Malamuth, a psychology student at UCLA, decided to test our reactions to pornography in a similar way and has spent his career researching the subject.

In an experiment in 1986, he recruited 42 men and assessed them on the "likelihood of rape" scale. Then he divided them randomly into three groups. The first was given a selection of sexually explicit materials containing scenes of rape and sadomasochism. The second was given non-violent pornography. The third group - the control - was given none at all.

About a week later, in what they thought was an unrelated experiment, each of the men was paired up with a woman, and told that she was not attracted to him. Then they had to play a guessing game, with the man having an option to punish the woman each time she got the answer wrong.

From this and many other experiments, Malamuth concluded that if a man is already sexually aggressive and consumes a lot of sexually aggressive pornography, there is a greater likelihood that he will commit a sexually aggressive act.

Some campaigners have used this research to claim pornography leads to rape - but Malamuth says that is too simplistic.

He draws an analogy with alcohol.

"For some people alcohol simply has the effect of making them more relaxed, letting them have more fun. For other people it's true that alcohol can increase the likelihood that somebody will behave in a violent way.

"But if I simply make the overall generalisation alcohol causes violence or leads to violence, you'd probably say that's glossing over a lot of the nuances.

"Similarly with pornography, for some people, it may be viewed as a positive aspect of their life and does not lead them in any way to engage in any form of anti-social behaviour. For some people who do have several other risk factors, it can add fuel to the fire."

Anti-pornography campaigners are concerned that extreme pornography is becoming mainstream.

Gail Dines, professor of sociology and women's studies at Wheelock College in Boston, believes it is a struggle to find non-violent pornography online.

"Even Jules Jordan himself, a very well-known porn director, has said they cannot keep up with the fans' desire for violent porn," she says.

That is disputed by computational neuroscientist, Ogi Ogas. He and a colleague, Sai Gaddam, collected data from a billion web searches and online porn sites, and says they found very little violent porn.

According to his data, most people looking for sexually explicit material online search for "youth". The next most popular categories are "gay", "MILFs", "breasts", and "cheating wives".

"Sexual interests are pretty monotonous," he says. "The median number of sexual interests that people search for was two. You search for the same thing day after day."

He was surprised by the popularity of so-called "granny porn".

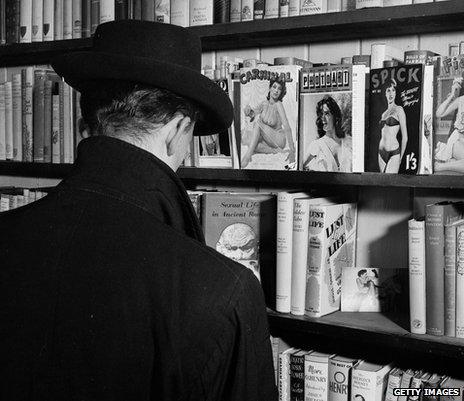

Pornography in the 1950s

"Women in their forties, in their fifties, even in their sixties are highly sought after," he reveals. "In fact Britain is one of the countries that has the greatest level of popularity for granny porn."

He calculates that one in six or seven internet searches are for pornography. Its prevalence and accessibility to children has led researchers to question what effect it is having on young people.

Earlier this year the UK children's commissioner asked academics from Middlesex University to review all the available evidence about the effect on adolescents. They excluded articles that had a very "particular ideological angle" or gave them a very low ranking - particularly if they also had methodological problems. They used a weight of evidence approach to rank the quality and relevance of the papers - and gave them a strength rating of high, medium or low.

More than 40,000 papers were submitted, but only 276 met their criteria.

Forensic psychologist Miranda Horvath and her colleagues were shocked by the quality of the research and by "how many very strongly worded, opinion-led articles there are out there which purport to be producing research, producing new findings when actually it's really based on opinion".

What did they conclude about the effects of pornography on young people?

"Pornography has been linked to unrealistic attitudes about sex, beliefs that women are sex objects, more frequent thoughts about sex, and children and young people who view pornography tend to hold less progressive gender role attitudes."

Most of the recent studies in this field have been correlational. That means you ask a sample of young people whether they've seen pornography, or how often, and then ask them what they think of sex or gender role attitudes, for example.

But it is not possible to establish causation from correlational studies, and to say whether pornography is changing or reinforcing attitudes.

"That is the real next step that research needs to take," says Horvath, "to try to identify which came first."

The only sure way to do that is with the kind of randomised, controlled experiments that Malamuth carried out at UCLA, where you expose people in the laboratory to violent pornography and observe what effects it has on them.

But Malamuth says he can no longer conduct such tests - in case he is right.

"We and other researchers have come up with a dilemma of ethics committees saying, well, we believe your effects are valid and, therefore, we're very afraid that at some point we might be sued if even one person claims that they went out and committed an act of rape by having been exposed to certain materials in your research."

In other words, it is unlikely that researchers will ever be able to prove that pornography is causing behaviour change.

Horvath believes it is time to give up looking for cause and effect and instead "focus on identifying young people's characteristics, vulnerabilities and strengths and how and why they might be related to their experiences of pornography".

The next step, she argues, is for researchers to broaden their questions to consider pornography in a wider context.

"You will often hear people saying, I saw a music video or I saw something on the telly which is very similar to what you would see in pornography.

"Young people see these sexualised images day to day in a whole variety of contexts and we don't fully yet understand how they process that, and how or whether they even do distinguish between, say, a music video and pornography."

Listen to Analysis on BBC Radio 4 at 20:30 BST on Monday 24 June or afterwards on the BBC iPlayer.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external