Taste and smell: What is it like to live without them?

- Published

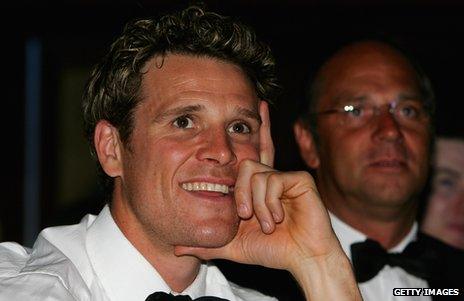

Double Olympic gold medallist James Cracknell says he is unable to smell or taste very much due to a brain injury he suffered. What is life like without these senses?

Duncan Boak lost his sense of smell in 2005 after a fall resulted in a serious brain injury. With smell said to be responsible for 80% of the flavours we taste, the impact of losing it has been huge.

"It's so hard to explain but losing your sense of smell leaves you feeling like a spectator in your own life, as if you're watching from behind a pane of glass," he says.

"It makes you feel not fully immersed in the world around you and sucks away a lot of the colour of life. It's isolating and lonely."

Like Boak, double Olympic gold medallist James Cracknell suffered a serious brain injury. He was hit by a petrol tanker while riding a bike in the US in 2010. In an interview with the Radio Times this week he said he was now unable to smell or taste very much.

Olympic gold medallist James Cracknell damaged his sense of smell in 2010

Eating is just something he has to do to survive, like putting petrol in a car.

The loss of taste, known as ageusia, is rare and has much less of an impact on daily life, say experts. Most people who think they have lost their sense of taste have actually lost their sense of smell. It's known as anosmia and the physical and psychological impact can be devastating and far reaching.

"Studies have shown that people who lose their sense of smell end up more severely depressed and for longer periods of time than people who go blind," says Prof Barry C Smith, co-director and founder of the Centre for the Study of the Senses.

"Smell is such an underrated sense. Losing it doesn't just take the enjoyment out of eating, no place or person smells familiar anymore. It is also closely linked to memory. Losing that emotional quality to your life is incredibly hard to deal with."

Sue Mounfield lost her sense of smell three years ago after having the flu. She says the smells she misses the most are not to do with food.

"It's things like smelling my children, my home and my garden. When they're gone you realised just how comforting and precious these smells are. They make you feel settled and grounded. Without them I feel as if I'm looking in on my life but not fully taking part."

Losing your sense of smell also makes the world a much more dangerous place. Even in the womb smell and taste are "gatekeepers" for allowing things into our bodies and rejecting harmful toxins, says Smith.

It nearly had extremely serious consequences for Alan Curr, who lost his sense of smell after knocking himself out in a gym lesson when he was eight.

"When I was at university someone left the gas on by accident. I was home all day but never noticed. At about 3pm my flatmates returned and I was in a bit of a daze but had no idea why. They smelt gas as soon as they walked in the door."

Boak says he only really started to understand why he was feeling depressed six years after his accident. He started to read about the sense of smell and had a "road to Damascus" realisation that it was the reason he was feeling such emotions. He has now set up the UK's first anosmia support group, Fifth Sense, external.

There are no official figures for how many people in the UK suffer from the loss of smell or taste, but estimates for the US and Europe put the number at 5% of the population.

Losing smell happens for several reasons. Some people are born without a sense of smell, it can be the result of a frontal head injury or something as mundane as an infection. Old age is also a factor, with smell and taste deteriorating rapidly after the age of 75.

Unexplained disturbances in smell and taste can indicate the onset of brain illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, often years before other more recognisable symptoms emerge.

"An unexplained loss of smell or taste acts like a canary in cage, it is a warning that something is wrong," says Smith. "People need to get it checked out quickly but they don't."

Often the problem is dismissed as trivial by the medical profession, adds Smith. Sufferers agree they are regularly turned away doctors who dismiss the loss of smell as trivial and say there is no treatment.

"Because you're not in pain many doctors basically just tell you to live with it," says Mounfield.

Outside the medical profession people often find it amusing and something of an oddity.

The physical consequences can also be extreme. People often lose weight because they no longer get any pleasure from food. Boak says he has been contacted by people who have been hospitalised because they find eating so difficult.

Whether or not anosmia can be cured depends on the underlying cause. Smell can improve for some people but never return for others. It can come back but odours might have been re-coded by the brain so things don't taste the same. Chocolate can smell like beef.

But unlike sight and hearing, you can improve your smell by training it, say experts. Studies have also shown this applies to anosmia sufferers.

Research by Professor Thomas Hummel, who runs the Smell and Taste Clinic at the University of Dresden in Germany, found that smelling certain strong odours - including rose oil, lemon and cloves - repeatedly over a 12-week period resulted in some improvement in olfactory function, external.

But for Boak it is a case of working with what he has left. With his taste buds still working he can bring out things like the sweetness and saltiness of food. Textures have also become important.

"I can even detect the different texture of different types tomatoes," he says. "Not something I thought I would ever have mastered before losing my sense of smell."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external