Escape from Alcatraz: Gavin Maitland's swim back to life

- Published

In 2008 Gavin Maitland underwent a life-saving double lung transplant. Five years later he swam from Alcatraz Island to San Francisco accompanied by his son and daughter - a feat that mirrored his journey back from the brink of death.

Zander's whole body briefly submerged out of sight as he jumped from the rear of the boat. As his head suddenly resurfaced, I could see the look of shock across his face. "Ahee, the water's cold!" he spluttered.

Splash! My daughter, Riley, hit the water a split second later, and she too surfaced with a look of horror on her face.

I had jumped from the boat moments before, and turned around to face them, treading water as I watched them join me in the icy waters of San Francisco Bay.

"Dad, dad, stay with me," Riley cried, as she frantically oriented herself in the water.

"It's OK, guys," I said, looking at their alarmed faces. "You'll get used to it in a few minutes." I hoped I sounded reassuring, but I too was surprised by the sudden surge of cold.

We were among a group of 10 swimmers braving the swirling waters and strong currents of the San Francisco Bay on a one-and-a-half mile (2.4km) open-water swim from the notorious Alcatraz Island to the mainland. It was 08:11 on Sunday 12 May 2013.

We turned and started swimming. The jagged assortment of buildings that made up the San Francisco skyline seemed so far away from our low vantage point. I could feel the cold water ripping across my face and hands.

Any initial uncertainty felt by Zander and Riley quickly disappeared. They were both swimming as hard as they could toward the distant shoreline with Mark, our kayaker guide, hovering reassuringly next to us.

Zander and Riley began steadily pulling away from me. I switched to breaststroke to catch my breath, then forced myself back into front crawl. As soon as I caught up, they sped off towards the shore again.

Mark paddled after them, turning around to me frequently. "Everything OK? Heart feeling strong? Breathing feeling good?" he asked.

I nodded. Yes, everything was absolutely fine. My breathing was heavier than I had anticipated, with the freezing water encasing my body, adding to the sheer exertion of swimming and the restrictions of my wetsuit.

But I felt physically strong and, most importantly, spiritually indefatigable.

"I want to swim from Alcatraz to celebrate my fifth anniversary," I announced at dinner one Sunday evening last October.

My wife, Julie, rolled her eyes. She said nothing, but I could almost hear what she was thinking: Oh great, another of his crazy ideas. Zander and Riley looked up at me. They did not say anything either.

The anniversary I was referring to was the five-year mark since my bilateral lung transplant on 14 March 2008. Lung transplantation is an incredibly complex procedure, and patients are typically judged on their post-operation survival at various stages - one year, three years, and five years.

VIDEO: 'You're waiting for someone to die or be killed so you can live.'

Outcomes for lung recipients are the worst of all transplanted solid organs.

It was a significant achievement to reach the five-year milestone, and I wanted to mark it with something special.

Water has always had a strong allure for me. I have always enjoyed swimming, in whatever lakes, ponds or oceans I can find.

The previous summer, one of Zander and Riley's swimming coaches had mentioned that she had competed in "the Alcatraz swim" a few years before. The Alcatraz swim? That really captured my imagination.

I did some research online and found that there were several companies that organised swimming expeditions and races. In my mind, it was conclusive - the open-water swim from Alcatraz would be the perfect way to celebrate my fifth anniversary.

"Think I can do it?" I asked to break the silence. "It's not too far, just over a mile."

"Sure," Zander said cautiously. He paused. "But I want to do it too."

"You too?" I said, somewhat surprised. "But you're only 13. The water will be really cold, you know. Cold, with waves, currents - maybe sharks."

"Sharks?" I had Riley's attention now. She paused for a moment, deep in thought. Then she said carefully, "If Zander's doing it, can I do it too?"

"Rye," I reasoned, suddenly nervous. "You don't even like the waves. The water's really cold, and it's a long way in the open water." Both Zander and Riley were very strong, competitive swimmers, but most of their experience had been in heated 25m swimming pools, with lifeguards and lane ropes.

"But you just said it's only a mile," she fired back with a hard stare. Her logic was incontrovertible. "I want to do it!"

"Yes, but Rye, you're only 11." I could feel my defences crumbling.

"I want to do it. With you and Zander," she confirmed emphatically. It was not a question any more.

"OK," I said, resignedly. I knew when I was beaten. "I'll look into it."

When I went online, I found a San Francisco-based swim expeditions group, so I got in touch and asked for more details.

Initially, I wanted to swim in March, exactly five years after my transplant, but Leslie, the group's founder, advised us to wait until May, when the water would be several degrees warmer.

"How old are your kids?" she asked.

"Thirteen and 11." Their ages sounded young even as I said them. "They're really good swimmers, though," I added.

"What's their experience swimming in open water?" She sounded hesitant.

Truthfully, none of us had a very convincing open-water swimming pedigree. Instead, I settled on telling her: "Living in Colorado, there's not so many opportunities for ocean swimming. However, they've both swum in lakes during triathlons, they train in a pool several times a week," I paused. "And they're pretty tough kids." Leslie seemed satisfied.

"Take a look at the training plans on the website for a preparation guide," she suggested.

The Alcatraz training plan set out a gradual build-up of distances, starting with three swims per week of around 20 or 30 minutes each, and steadily increasing distance and intensity.

So we started training. Zander and Riley were already on a swim team, and had regular practices. I took the opportunity to swim too while they were in the pool, and I easily chalked up 1.6km (one mile) in an hour.

As the weeks went on, I trained diligently, enjoying the excuse to be in the water almost every day. I swam this way from January until April, and felt confident that I was in reasonably good condition for the challenge.

The day of the swim started early. Zander, Riley, Julie and I rose at 06:00 in our hotel room in San Francisco, wide awake with anticipation. We had flown in the day before from our home in Boulder, Colorado. Our wetsuits were neatly laid out in the room, and we pulled them on as we wolfed down mouthfuls of omelettes and toast.

With jackets, hats and bags full of dry clothes ready, we left the hotel room and hailed a taxi. We were the first ones at the meeting point, looking out across the calm waters of San Francisco bay as the sun came up.

I put my pack against a tree, stretched briefly, and started a warm-up run along the walkway next to the sandy beach. With my new, transplanted lungs, it takes me longer than most people to open the small airways so oxygen can flow more easily.

I reached the end of the walkway, turned around and ran back, striding faster and faster as I neared the end.

I slowed down and stopped, panting heavily.

"Hi, I'm Mark," said a man with an outstretched hand. "I'm your kayaker this morning." He was in his early 50s, with shorn hair, sparkling eyes and a wide grin.

I introduced him to Julie, Zander and Riley. He told me he had done the crossing dozens of times, that that we just needed to follow his directions, and we would easily make it to shore.

I checked my watch. Drug time. I had carefully adjusted my morning dose of Prograf, the immunosuppressant drug I take twice a day, exactly 12 hours apart.

I pulled out my tiny box of pills, and gulped down three capsules. In the few months after my lung transplant, I often resented having to comply with a strict drug regimen that is a life-saving necessity for all organ transplant recipients.

Now, five years on, I gulped them down with the enthusiasm of a labrador devouring his breakfast, wholly appreciative of the vital role they play in keeping me healthy and alive.

There were 10 swimmers on the grassy slope at 07:15 that morning. I stood with the others, suited up and eager with anticipation, Zander and Riley on either side of me.

"You have all been assigned to your kayaks, so ensure you stay close at all times, and please stay within 25 yards of each other as you swim," Leslie reminded us.

"You will be swimming across two rivers, one flowing from the Golden Gate Bridge from west to east. Once you cross that, there is a second river flowing in the opposite direction from east to west. So watch the currents and keep sight of your target building on the skyline."

We walked together around the walkway and on to the 30ft (9m) support boat that would take us out to the island. Within minutes of casting off, we were motoring out towards the mesmerising, forbidding island of Alcatraz.

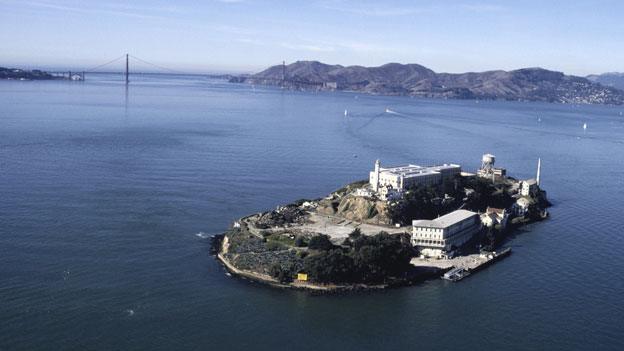

Alcatraz, the small island often referred to as "The Rock", was developed with facilities for a lighthouse, a military fortification, and, most famously, a prison from 1933 until 1963.

While several well-known criminals, such as Al Capone, served time on Alcatraz, most of the 1,500 prisoners incarcerated there were not high-profile.

During its 29 years as a prison, the penitentiary never logged any successful escapes. Potential escapees were either shot dead or assumed drowned in the frigid waters of San Francisco bay.

In 1962, three would-be escapees disappeared from their cells in one of the most intricate attempts ever devised - portrayed in the 1979 movie Escape from Alcatraz, starring Clint Eastwood.

Although no evidence was found that these famous prisoners died in their attempt, they are officially listed as "missing, presumed drowned".

As the support boat pulled up alongside the island, I looked back at the San Francisco skyline. The proximity was striking.

It has been said that prisoners on Alcatraz were often tantalised by the sounds of normal city life, maddeningly close just across the water but, at the same time, as good as a million miles away.

Was the shore really that close? I felt the rush of exhilaration as Leslie began instructing the swimmers to jump.

Exercise is strongly linked to recovery in lung transplant patients. After the operation, I exercised at least in line with the doctors' recommendations, and often a lot more.

After 13 months with my new lungs, I competed in my first sprint-triathlon, consisting of a 750m swim, a 20km cycle ride and a 5km run.

Out of all the competitors, I placed dead last, but I didn't care. Getting back to swimming was a natural progression in the process of recovery.

The three of us swam closely together for the first 20 minutes, alternating between front crawl and breaststroke. Mark continued to shout encouragement from the kayak.

Zander and Riley had quickly acclimatised to the cold water and began to enjoy the sensation of being tossed around in the water. I could see their bright green caps just in front of me and hear their high-pitched voices as they bantered back and forth.

I concentrated on my swimming, pulling slow steady strokes, and aimed for the buildings silhouetted on the skyline.

After half an hour, Zander and Riley were getting impatient.

"C'mon, dad!" they shouted as they waited for me to catch up. I would break into front crawl but as soon as I got to them, they would dart forward and leave me behind again.

I felt like a stage performer doing his best to entertain a restless audience, only to be mercilessly heckled.

"Wow," I thought to myself. "They're a tough crowd."

Distances in open-water swimming are deceptive. For most of the time, it seems as if you are getting nowhere, as the scenery does not change.

You have to trust that you are still moving slowly and steadily through the water, closer and closer to dry land. The huge expanse of water can be mentally overpowering, especially if you dwell on how deep the water is beneath you and how endlessly it stretches on all sides.

'I'm so happy dad has gone from sick to Superman'

Even so, there is something soothing and relaxing, even spiritual, about swimming in open water. The waves gently move you up and down, and you feel the silkiness of the water on your exposed skin.

A couple of times I flipped over and did a few strokes of backstroke. The sensation was amazing - all I could see was the expanse of sky above me.

But I was unable to tell where I was heading, so after a few seconds I flipped back on to my front.

Out in the vastness of the San Francisco Bay that morning, I revelled in the energy of the ocean and the gift of breath that buoyed me on this adventure.

No-one knows why my lungs failed when I was 41. I am an unusual case.

The pathologist at my transplanting hospital gave the disease a unpronounceable 43-letter name. "It's some kind of pulmonary fibrosis," he said, "where the soft lung tissue becomes hard and useless."

His official conclusion was: "We have no idea what caused your lung disease."

A lifelong non-smoker and fitness enthusiast, I enjoyed perfect health up to my mid-30s. I swam and ran competitively in school and all the way through university. After graduating, I took up running 10km races, as well as half and full marathons.

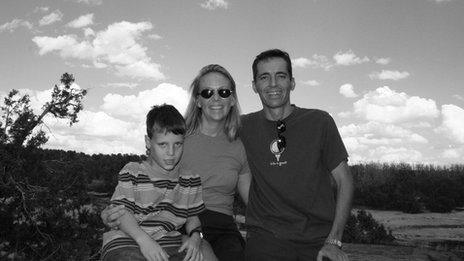

Gavin Maitland before the transplant

The decline of my lungs began with a persistent, dry cough. At first I waved it away as an irritant, but it would not leave.

I consulted my general practitioner, who thought it may be asthma, but was not sure. Months passed and I consulted many different doctors, dissatisfied with their lack of diagnosis or treatment.

One specialist pulmonologist, looking up from a freshly-minted computed tomography (CAT) scan, admitted: "Honestly, I'm perplexed."

Time went on, and my tolerance for exercise lessened, my breathing became more laboured, I was noticeably thinner and still no-one could tell what was wrong.

Five years after the cough began, Julie frantically drove me to the hospital one memorable Saturday morning after I lay down on the floor and could not get up.

I could read the concern on the faces of the hospital pulmonologists. The chest X-rays were a mass of white, my oxygen saturation level was below 90% and I could not stand on my own.

Over the next few weeks, a succession of bad news was broken to me. I was told that I only had six months to live and my only chance of survival was a bilateral lung transplant.

And then, after weeks of consultation, testing, appointments and procedures, a transplant physician at the hospital telephoned Julie and told her that they did not think I could survive the transplant procedure, so they did not want to accept me as patient any longer.

In the following three frenetic months, Julie researched, identified and contacted 17 different transplant hospitals across the country, and followed up tenaciously with phone calls and emails.

Amid an avalanche of rejections, one hospital eventually responded positively. Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, said, yes, we might be able to help, come on over.

I hurriedly arranged a one-way plane journey, and before long - carried by hope and in-flight oxygen - I was on a transplant waiting list.

Soon after, there followed the tragic death of a young man, the heart-wrenching decision of his family to donate his organs and the roller-coaster ride of logistics, 21st Century medical genius, raw emotion and arduous recovery that all goes together to make up an organ transplant.

WATCH: The brother of my donor has invited me to his wedding

Prior to the operation, I could only breathe in short, shallow gasps.

When I woke from the anaesthetic, I inhaled the most beautiful, deepest and longest breath that I could ever imagine. Despite the searing pain in my torso, I felt like standing up on my bed and cheering.

People often refer to lung transplant as a "second wind", although transplant doctors emphasize that transplant is not a cure, but simply the exchange of one acute condition for another.

The current average survival period of a lung recipient in the US and Europe is five years.

Statistics say that the current 10-year survival rate of a lung transplant patient is 30%, meaning that only one out of every three patients will celebrate their 10th anniversary.

So how long will my second wind last? I honestly don't know. Statistics undoubtedly tell a story, but it's partial.

I know a man in his early 40s who is 10 years post-transplant and a woman in her mid-50s who is 17 years post-transplant.

My pulmonologist told me recently that he rated my health in the top 1% of his transplant patients. As a result, I remain optimistic that I will be around for quite some time yet.

As we neared the entrance to Aquatic Park, Zander and Riley surged forward with a new kayak escort while Mark kept his eye on me.

Cramp spread suddenly from my left leg to my right leg. Both legs locked and I knew I could not swim through it any more.

I needed drinking water in a few seconds or I would be contorted in agony.

I signalled to Mark that I needed some help. He was next to me in an instant. "Cramp!" was all I could grimace, as the pain shot through both legs.

"Sorry," I gasped. "I need to get out."

"But you're so close," he shouted. The entrance to the Aquatic Park was only 200 yards (182m) away.

The support boat powered up next to me, and I grabbed the rail at the back and hauled myself on to the back of the boat. Julie thrust a bottle of water into my hand. "Drink!" she yelled.

I tilted my head back and drank the whole bottle in a continuous gulp. Almost instantaneously, the cramp that had hijacked and tormented the muscles in both my legs eased, then evaporated.

I pulled on my swim cap back on, adjusted my goggles, and jumped off the back of the boat again into the water. I had been out of the water for less than five minutes.

This time, in contrast to our initial entry, the water felt deliciously warm and welcoming.

By now, Zander and Riley were small dots in the distance, already on the beach. I swam determinedly towards the shore, focusing on the finish.

A giant sea lion turned lazily in the water about 20 yards (18m) in front of me, reminding me of the jokes we had made about sharks before the swim.

People often wrongly associate the San Francisco bay with shark attacks, and this supposed danger was a frequent comment from our friends on hearing about our proposed swim.

In reality, there have been no recorded shark attacks in the history of the bay. The myth probably originates with prison guards who would tell inmates that the waters were shark-infested to deter escape attempts.

The sandy shore was just in front of me. I tried to put my feet down, but it was still out of my depth. Two, three more strokes.

I tried again, and I could feel the gritty bottom.

I pulled forward, then stood up in the water and waded on to dry land.

I was struck by the silence and peace of this sunny Sunday morning. All of a sudden, I felt overwhelmed by a surge of energy, and I started to run across the beach towards my children, water gushing from my wetsuit.

I was shivering wildly, but did not feel cold. I was hugely elated.

"Zander, Rye! Great job! You did it. We all did it!" I grabbed both of them and hugged them tightly. The swim had taken us just over an hour.

They let me hold them for a few moments.

"Dad!" Riley pulled back and looked up at me sternly. "Dad, next year…" she paused. "Next year, you'll need to have your own kayak."

"OK," I said, grinning. "OK."

Like I said before, tough crowd.

So where to go from here? Will we swim Alcatraz again next year?

Maybe. But perhaps there is another challenge to set our sights on? I read recently about another open-water swim that crosses the Dardanelles, a narrow strait in north-west Turkey, formerly known as the Hellespont.

The English poet, Lord Byron, famously swam it in 1810, the first swimmer to make the crossing in modern times, in honour of the Greek mythological figure, Leander. It looks like a great swim, only three miles (4.8km) across from Asia to Europe.

I wonder when it would be a good time to mention this to Julie?

Videos by Anna Bressanin

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external