A Point of View: Bert, Ernie and the power of cartoons

- Published

They are firm friends who live together. And Sesame Street's Bert and Ernie have been cast in a larger drama about equal marriage, says Sarah Dunant.

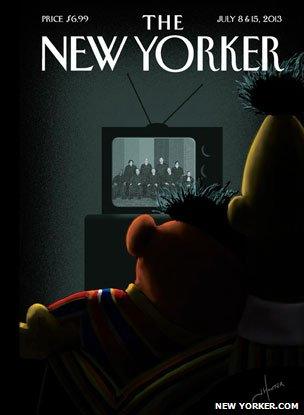

If you know the New Yorker magazine, you might well have seen what I am about to describe. But I'll tell you anyway, because the cover of the last edition is a corker. On the right in soft glowing colours are the backs of Bert and Ernie, two characters from the US children's TV series, Sesame Street. Ernie, small and squat, is leaning his head affectionately on the taller Bert's shoulder - their identical tufts of hair sticking up like spiny corals on bare rock.

The mood is one of domestic intimacy, made more so because they and we (over their shoulders) are looking into a darkened living room, illuminated by the ghostly flicker of a 1950s black and white TV set. And on the screen, a tableau of nine seated men and women in sober black robes staring out at them.

Like many of the best New Yorker covers, it is instantly arresting, with such a strong sense of atmosphere that you're smiling even as you are still decoding its meaning. In this case, a seminal moment in American social and constitutional history.

Those six men and three women on the TV screen make up the Supreme Court of America and the ruling they've just handed down is to declare the Defence of Marriage Act - the law which barred the federal government from recognising same-sex marriages as legal in some states - as unconstitutional in violation of the Fifth Amendment. In other words, when it comes to matters of social security, tax and immigration, if you are married in the eyes of your state, you are now also married in the eyes of your country.

It was, not surprisingly, a controversial ruling. Five to four was the vote. For many Americans it will be seen as a further nail in the coffin of a Christian nation on the fast track to hell. It's worth remembering that 35 US states still ban same sex marriage. For others, it was a sweet victory.

And the New Yorker cartoon very much captures that sense of sweetness by the addition of Bert and Ernie, the inseparable odd couple from Sesame Street who with their bickering, gruff but affectionate and clearly committed relationship have been seen by many as gay icons for years. If you are one of those who haven't noticed it yet, think about it next time you see them.

Not everyone has been charmed by the use of the puppets and the attacks have come from both sides of the political fence.

The National Review, not the most liberal of publications, re-ran the image with the strap line "Innocence. Lost." Which was clearly as much to do with the state of Bert and Ernie as the state of the nation.

Inside the gay community, there were those who found it too soft. One view was that using puppets "infantilised" gay people, given the long and sometimes vicious struggle they have had to get to this point. Another that while Bert and Ernie may be a culturally witty reference, as couples go they're still firmly in the closet.

Their original creator, Jim Henson (more of him later) has been dead for many years now so cannot add his voice, but the Sesame Workshop, with its global reach, has been clear right from the start that they are having none of this gay representation stuff: "Bert and Ernie are best friends. They were created to teach pre-schoolers that people can be good friends with those who are very different from themselves. Even though they are identified as male characters and possess many human traits and characteristics (as most Sesame Street Muppets do), they remain puppets and do not have a sexual orientation."

One can almost see Ernie guffawing away at this - though, obviously, in a totally non-sexually orientated manner.

It's a coherent position. In a world where sex and sexual advertising is everywhere, Sesame Street is in the business of enchanting and educating children in that magical space - a commercial free zone. To use its icons in any campaign might seem to undermine its integrity. If you want subversive or sexualised puppets, then try Team America from the creators of South Park, a film which offers a full and free exploration of what puppets can do with almost all moving bodily parts. It's possible that I have never quite laughed so much.

Same-sex marriage supporters in the US celebrate the Supreme Court ruling

This argument over the purity of Bert and Ernie is its own tribute to the huge success of Sesame Street over nearly 50 years. Those cartoon characters - or their puppet equivalents - which touch us at our most formative moments of early childhood will become part of the bedrock of our cultural belonging. You may or may not like Walt Disney, but the chances are both you and your children will have had an early brush with parental death through THAT scene in Bambi.

More specifically, 1950s children who still know the strapline for Bill and Ben the Flowerpot Men will have a vision of a drab, conservative but essentially decent post-war Britain, which both succoured them and gave them something to rebel against. Or perhaps I'm just talking about me.

If you want a similar moment of Bert and Ernie cartoon subversion in 1960s Britain, you only have to go to the Oz obscenity trial, where the school kids' edition of the satirical magazine (edited by 17-year-olds) gave the goodie-goodie Rupert Bear - with his trademark yellow check trousers - genitals. Children, it was saying, grow up. And have things to say about the society that bred them, in this case challenging attitudes to authority and sexuality.

When it comes to Sesame Street, that idea is compounded by the fact that it has been a companion to many generations of children now. Some of those who later found themselves to be gay, or had friends who were, are surely entitled to find echoes of more mature relationships in the characters. Don't tell me Kermit and Miss Piggy don't sometimes remind you of certain dysfunctional heterosexual couples you've come across. If children's cartoons are preparing us for life, then surely taking them with us into adulthood is a mark of their success rather than their failure.

When it comes to my own children's experience they - and I - hit gold early. More or less as soon as they could read, someone introduced us to Calvin and Hobbes. The comic strip by American Bill Waterson was syndicated in various newspapers. (It's worth noting that mass-produced children's cartoons first arrived at the end of the 19th Century as part of a newspaper war - the funnies section a kind of pre-runner to TV, a way to keep the kids quiet while the adults got on with adult business).

In our house, however, we got the cartoon in annuals - the perfect way to immerse yourself into the alternative universe of Calvin, a precocious six-year-old with fire-cracker energy, and Hobbes, his soggy stuffed toy tiger, who, as soon are they are alone together, becomes his partner in crime and philosophising best friend. Their names - theologian and philosopher - were of course deliberate.

While Calvin's parents tear their hair out trying to handle this chaos of child dynamism, tiger and boy explore together the great existential questions of life, while still finding time to roll in the snow, torment a girl and travel through time and space. To this day my daughters, now in their 20s, keep an album by their bed. As, I happily admit, do I. In our family, when the going gets tough, the tough turn to Calvin and Hobbes.

It was while writing this that I discovered that Bill Waterson gave up the cartoon in 1995 after only 10 years of creation. Until the end of time, there will only ever be 3,150 Calvin and Hobbes strips. Enough to secure immortality in my eyes.

Which brings me to Jim Henson, puppeteer, producer, director and the mastermind behind the Muppets and deeply involved in Sesame Street, who died far too early from pneumonia at the age of 54 in 1990. A friend in New York told me a story that she heard just after his death. A little girl, aged five or six, was at the breakfast table and saw on the font page of the paper a picture of Kermit, marking the news. "Kermit? Why is Kermit in the paper?" she asked. Her parents, taking a deep breath and preparing themselves for the "early reference to death" conversation, replied: "Because the man who made Kermit has died." She looked at the picture stricken for a moment. "Does that mean Kermit is dead?"

"Oh no, darling. Kermit is still alive." (What lies parents tell even as they strive for the truth.)

"That's OK then," the child said, climbing off her stool and heading off into the rest of her life.

Long after we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Kermit, like Bert and Ernie, will live on. Future generations can at least be sure of the frog's sexual orientation. Miss Piggy will see to that.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external