Brazil's new generation of Thalidomide babies

- Published

Alan's family asked that he not be identified

A new scientific study seen exclusively by the BBC indicates that the drug Thalidomide is still causing birth defects in Brazil today. It's been given to people suffering from leprosy to ease some of their symptoms, and some women have taken it unaware of the risks they run when pregnant.

Thalidomide was first marketed in the late 1950s as a sedative. It was given to pregnant women to help them overcome morning sickness - but it damaged babies in the womb, restricting the growth of arms and legs.

About 10,000 Thalidomide babies were born worldwide until the drug was withdrawn in the early 1960s. In most countries the Thalidomide children became Thalidomide adults, now in their 50s, and there were no more Thalidomide babies.

But in Brazil the drug was re-licensed in 1965 as a treatment for skin lesions, one of the complications of leprosy.

Leprosy is more prevalent in Brazil than in any other country except India. More than 30,000 new cases are diagnosed each year - and millions of Thalidomide pills are distributed.

Researchers now say 100 Brazilian children have injuries exactly like those caused by Thalidomide.

"A tragedy is occurring in Brazil... it is a syndrome which is completely avoidable," says Dr Lavinia Schuler-Faccini, a professor at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

But campaigners, doctors and leprosy sufferers say the drug is vital. They believe the benefits outweigh the risks.

Inside a Brazilian Thalidomide factory

Schuler-Faccini and other researchers from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre looked at the birth records of 17.5 million babies born between 2005 and 2010.

"We looked at all children with limb defects and those with the characteristic defects of Thalidomide," Schuler-Faccini says.

"We compared the distribution of Thalidomide tablets… with the number of limb defects and there was a direct correlation.

"The bigger the amount of pills in each state the higher the number of limb defects."

In the same 2005-2010 period, 5.8 million Thalidomide pills were distributed across Brazil.

"We had about 100 cases in these six years similar to Thalidomide syndrome," says another of the research team, Dr Fernanda Vianna.

"We couldn't evaluate each case, we cannot say that all are cases of Thalidomide syndrome, but this type of defect is very rare."

Poor health education and widespread sharing of medicines may be to blame, she says.

This is what seems to have happened to Alan, who we meet in a small town in central Brazil.

Such is the taboo about his injuries, his family asks not to be identified.

He was born in 2005. He has no arms or legs. His hands begin just below is shoulder blades, his feet close to his hips.

He laughs a lot and loves to play computer games with his brothers.

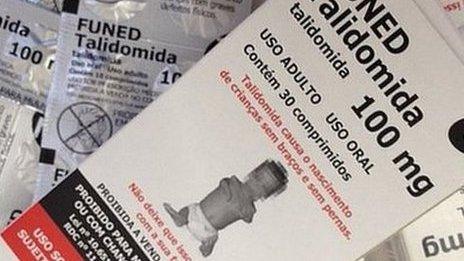

There are clear warnings on Thalidomide packets and it is strictly regulated

He rolls his body to get around the house, and when going further afield is strapped into a wheel chair.

He is well looked after and has one-to-one tuition at school, but he must travel two hours by bus to the nearest town each week for physiotherapy.

His mother Gilvane took Thalidomide by accident. Her husband was given it for his leprosy and kept the pills mixed up with others.

"I took it when I was feeling sick, not feeling well, so I got the medicine and took it. I had already taken others like Paracetamol, to make myself feel better, without knowing I was pregnant.

"His father said that the doctor didn't tell him that women couldn't take it. He said they didn't tell him anything about it."

There are strict regulations around the drug. It can only be prescribed to a woman who is taking two forms of birth control and agrees to regular pregnancy tests.

There are clear warnings on the packets and there is a picture of a child damaged by Thalidomide.

But leprosy is a disease of the poor, in areas where healthcare is patchy and education is inadequate.

And plenty of people in Brazil argue that Thalidomide should continue to be used.

"Nowadays there is a myth about Thalidomide," says Mariana Jankunas, production co-ordinator at FUNED, a state-owned manufacturer of the drug.

"I think with information and publicity about the benefits that Thalidomide brings to patients this myth can be overcome, because the benefits outweigh the risks."

Doctors who prescribe the drug agree.

"It is the best drug," says Dr Francisco Reis, from the Leprosy Clinic at Curupaiti Hospital near Rio de Janiero.

When I tell him that many people may be shocked to hear Thalidomide is still being used he responds: "You have the ghosts of Thalidomide in the 50s, but you should forget those ghosts."

He introduces us to one of his patients, Tainah, who shows us how the medicine has reduced the debilitating lesions on her arms.

"I know that I need the medicine," she tells us.

She says she understands that if she doesn't take contraceptive pills she could get pregnant and give birth to a disabled child.

Brazil is a country of enormous inequalities where 20% of the population live below the poverty line.

Angus Crawford reports from Brazil

Overcrowded housing and poor health systems are common to both rural areas and the slums of the cities - places where leprosy thrives.

Where the disease is most common Thalidomide will continue to be prescribed and the risk of babies being born terribly injured will remain.

Artur Custodio from Morhan, the national leprosy campaign group, recognises that the medicine is dangerous, but says it's cars that cause most injuries and disabilities in Brazil.

"We don't talk about banning cars, we say we should teach people how to drive responsibly," he says.

"It's the same thing for Thalidomide."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external

- Published26 April 2013

- Published27 April 2013

- Published2 June 2012

- Published1 September 2012

- Published1 September 2012

- Published1 September 2012

- Published3 November 2011