Are there too many managers?

- Published

Once upon a time there were only workers and owners, but then the age of the manager dawned, explains Lucy Kellaway.

There are five million managers in the UK today, 10 times as many as there were 100 years ago.

Even if you don't actually manage anyone, your title pretends you do. A conductor is a train manager. An administrator is an office manager. A technician is an IT manager.

We've all become obsessed with management. Any self-respecting executive will now have an MBA, a shelf full of management books, and a vocabulary stuffed with "key deliverables" and "scalable solutions".

And yet we were able to get through the industrial revolution without having any "masters of business administration" at all. No-one thought of management then - the very word manager wasn't widely applied to business until the 20th Century.

"There's an earlier set of meanings of management, one is to do with managing the household, from the French word menager," says Chris Grey, professor of organisation studies at Royal Holloway University.

"But it also has a meaning, in popular early 19th Century culture, of dishonesty. A manager was someone who will run off with your money. Someone like a cowboy builder taking your business, getting control of it, and running off. Manager meant something quite disreputable, quite unprofessional."

In The Wealth of Nations, author Adam Smith shares his suspicions.

"The directors of companies, being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot well be expected that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private co-partnery frequently watch over their own."

In the UK, we still distrust our managers, sometimes with good cause. The way Fred Goodwin brought down the Royal Bank of Scotland wouldn't have surprised Adam Smith at all. We are suspicious of them not just because we don't know what they do - we fear they don't know either.

But at the end of the 19th Century an engineer from Philadelphia came along with a very clear idea of what management was all about - efficiency.

Frederick Taylor was the world's first management consultant and his fad became known as scientific management.

Has Fred Goodwin fuelled the UK's distrust of managers?

He believed that for any given process, there was one best way to do it. The average worker, he thought, was pretty dim and hopeless and so the answer was a rigid system with a manager in charge of making it happen.

"It is only through enforced standardisation of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced co-operation that this faster work can be assured," he said.

"And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this co-operation rests with management alone."

Taylor's beloved time-and-motion studies were initially used in factories, but it wasn't long before they reached the office.

His disciple William Leffingwell began applying these methods to clerks in the early 20th Century. He became obsessed with how they opened the mail and saw "a lot of tiny, ineffectual motions" such as reaching twice for pins because the pin tray had been moved a couple of inches.

He was a stickler for a tidy desk too.

"Desk system should be taught to all the clerks and close watch kept until they have thoroughly learned it," he said.

"To ascertain just how well they are proceeding, suddenly ask for an eraser or a ruler, or some other item that is not in constant use, and see how long it takes to locate it. If it cannot be located at once, without the slightest loss of time, the lesson has not been learned."

Detail delighted him - he even got one of his underlings to make a time study on how quickly ink evaporated and worked out that inkwells of the non-evaporating variety would save $1 per inkwell per year.

This kind of pettiness is still to be found in most offices today. It explains why free chocolate biscuits inevitably get replaced by plain ones. Some clever accountant finds costs are saved twice over - plain biscuits are cheaper, and are also nastier, so fewer get eaten.

But in the UK scientific management was never taken up with much enthusiasm, which was mainly because, at least until the second half of the 20th Century, British managers were pretty much amateurs.

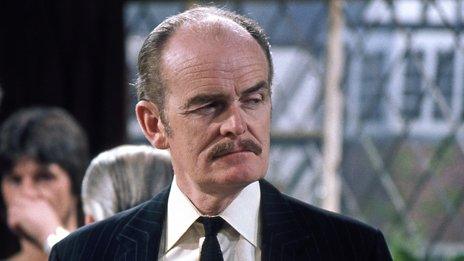

John Barron as domineering boss CJ in The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin

After World War II, all our proudest companies were run not by people who had the first clue about business but by generals. There was one apiece at British Railways, British Airways, at Vickers, and even at the BBC. They believed in one thing only - hierarchy.

These managers didn't think they had anything to learn, which was partly why the first proper business school in the UK didn't open until 1965, more than a century behind the US and Europe.

When the British heard of the new management science being developed in the US, their response was to laugh. They had their own methods of reinforcing the office pecking order.

The super swanky manager's office from Barings Bank in the late 1890s is now on display at the Museum of London.

The elaborate desk has a fine green leather covering and the floor is covered in a bright red Axminster carpet. There are paintings on the wall and a top hat on the coat hanger.

Something that I particularly like is that it leaves you in no doubt who is the most important person in the room - the manager has a leather swivel chair, while the visitor has a little chair.

"If the chief clerk came in, he probably had to stand," says Alex Werner, head of collections at the museum.

"The chair is for visitors from other banks."

But with the growth of corporations in the first half of the 20th Century, the march of management wasn't to be stopped. And with so many more managers, some of them need to be managed themselves - hence the middle manager.

Being effective in this new role required a whole new set of skills.

Office layout and seating can be psychological tools to indicate power

According to the American sociologist C Wright Mills, a successful manager had to "speak like the quiet competent man of affairs and never personally say no. Hire the No-man as well as the Yes-man. Be the tolerant Maybe-man and they will cluster around you filled with hopefulness. And never let your brains show."

Excellent advice all round. The Maybe-man still fares pretty well in offices some 60 years later - though brains have possibly staged something of a come back.

But back then there was no talk of diversity, let alone authenticity. It was all about conformity and hard work.

According to the sociologist William Whyte, managers required a range of qualities.

"Today the executive must appear to enjoy listening sympathetically to subordinates and team playing around the conference table," he said.

"It is not enough that he work hard now, he has to be a damn good fellow to boot."

As for work-life balance, there wasn't any. One sales manager confided in Whyte: "I sort of look forward to the day my kids are grown up. Then I won't have to have such a guilty conscience about neglecting them."

With the expansion of management came an equal expansion in job titles, which were both a way of labelling people and cheap way of making status-conscious men happy.

Office Magazine summed it up in October 1955:

"It may well be that the duties of Mr Bloggs - an employee of many years' standing - are, strictly speaking, those of a senior clerk, but it will do his firm no harm, to confer an 'Inspectorship' upon him. And it will probably do Mr Bloggs' morale a power of good to sign his name above with such a title, not to mention enabling his wife to hold her own in conversation with that odious Mrs Jones whose husband, as she never allows one to forget, is Manager of Makepeace and Farraday's Export Branch."

The cult of management with its unwritten laws and petty titles was changing the way outsiders saw offices. The fictional hero was no longer the skeletal scribe but a middle manager working in a world that could have been invented by Kafka. CS Lewis describes it in the Screwtape Letters:

"I live in the Managerial Age in a world of Admin. The greatest evil is not now done in those sordid dens of crime that Dickens loved to paint. It is not done even in concentration camps and labour camps. In those we see its final result.

"But it is conceived and ordered (moved, seconded, carried and minuted) in clean, carpeted, warmed and well-lighted offices, by quiet men with white collars and cut fingernails and smooth shaven cheeks who do not need to raise their voices."

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Lucy Kellaway's History of Office Life, produced by Russell Finch, of Somethin' Else, for Radio 4. Episode seven, Sex and the Office, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 30 July