Crossrail: Where is it in the list of 'big digs'?

- Published

The tunnelling for Crossrail, London's new east-west rail network, is now in its most intense phase - and the scale of the engineering challenge is as jaw-dropping as the cost is eye-watering.

The tourists and shoppers in Red Lion Street in central London can have little idea that 30m under their feet something is going on, although people in buildings with deep foundations may feel a curious tingle.

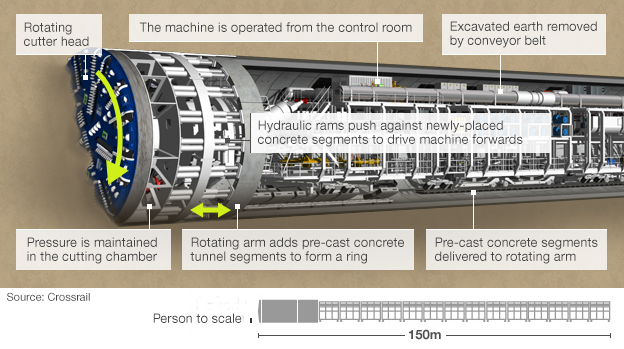

Two tunnel boring machines (TBMs), named Phyllis and Ada, are worming their way through the earth. Each one is the length of 14 London buses and weighs 1,000 tonnes.

A computer display in Phyllis's control cabin shows the machine is 18mm below where she should be and 27mm too far to the left. But that's all within the design's tolerance of 50mm.

"Fifty millimetres is very small in engineering terms," says Andy Alder, project manager for Crossrail's western tunnels. "When you think that this machine is 7m in diameter, to steer it within two inches is a pretty fantastic achievement."

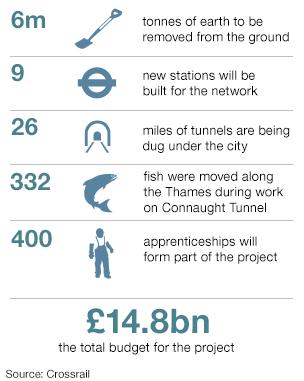

Europe's largest current construction project is now halfway through, having absorbed over 25 million working hours and produced around eight miles of tunnels. Last year and this year the project supported the equivalent of 13,800 full-time jobs throughout the supply chain.

When the project is completed in late 2019, the route will start in Maidenhead in Berkshire, stretch out a tentacle to Heathrow, then pass through central London before going on to Shenfield in Essex and Abbey Wood, near Greenwich. It will bring one and a half million people within a 45-minute travelling distance of central London.

The TBMs have tungsten carbide cutting tools on the face that cut away the ground, with the loose earth fed back down the machine on a conveyor belt. What happens to all that debris? Much of it - 4.5 million tonnes - will eventually form the new RSPB nature reserve of Wallasea Island.

After the TBM has cut out 1.6m of ground, pre-cast concrete sections are fed forward and lifted by pistons to form a 22-tonne ring around the tunnelled ground. Then the machine shunts forward on its 22 hydraulic cylinders, which have a pulling force that could lift 2,900 London taxis.

Working 24 hours a day, a TBM can tunnel 100m a week.

Since it takes 45 minutes to reach the machines from the ramp at Royal Oak, crews have all the facilities they need on board, including a canteen, office and a safety chamber with an emergency oxygen supply.

"I'm an underground kind of person now," says Jim Gagan, lead miner on Phyllis. "Although it's nice to get out and about during the day, when it's raining something silly upstairs it doesn't affect us down here - and it's nice and warm in the winter."

Crossrail will bring a new commuter line to central London from 2018-2019

The twin tunnels stretch 13 miles and necessitate the removal of 6m tonnes of earth

Tunnel boring machine Phyllis is named after Phyllis Pearsoll, creator of the London A-Z

The control cabin within a tunnel boring machine, showing soil pressure and position

The works go unnoticed by Londoners on Red Lion Street, 30 metres above Phyllis

Gagan says that he worked his way up "through shovelling things at the back". His father was also a tunnel miner, who worked on the Channel Tunnel.

According to Mike Black, Crossrail's top soil engineer and a Channel Tunnel veteran, the London project is more complex.

In particular, the nine new stations, some of which require huge underground excavations, pose the risk of displacing London's soft clay and sand. As the TBMs move through the ground, the earth at the tunnel face is kept under pressure - and all the roads and buildings directly above are monitored around the clock for any movement.

"We have seen movement and we expected to see movement," says Black. Structurally the buildings are not affected, but Crossrail will have to pay to redecorate when cosmetic damage happens.

So far, all the movements detected fall within the predictions of 10mm or less. Crossrail engineers inject grout into the earth underneath buildings to fill any voids that may have appeared and lift the buildings back into position.

Subterranean London is riddled with Tube tunnels, secret passages, Roman ruins, high-voltage cables, long-forgotten aquifers and deep building foundations. The route squirms past these obstacles, passing just 1.5m over the Tube's Northern Line.

During the long desk-phase that preceded tunnelling, designers scrutinised yellowed plans for London buildings.

For some, they had diagrams of what was actually built. For others, they just had the initial plans. Crossrail's surveyors estimated the size of foundations by examining buildings.

Then there was the problem of bombs.

This map, used by 6Alpha, was updated during the war - areas shaded black denote total destruction, purple damage beyond repair, dark red probably unrepairable and lighter colours less heavy damage

"It's estimated that there's about 17,000 tonnes of bombs that were dropped on London in WWII and the rule of thumb is about 10% failed to explode," says Simon Cooke from consultancy 6Alpha. While some bombs were removed, others were missed or even abandoned because they were too dangerous to deactivate.

6Alpha studied records kept by wartime ARP wardens, local authorities, and at times even the Luftwaffe, to identify areas along the route which presented the biggest unexploded ordnance threat.

Separate contractors were then sent to survey these areas. So far, no unexploded bombs have been found.

Crossrail's engineers have found a few unpleasant surprises though. It had been planned to use the Victorian Connaught Tunnel that runs under London's old docks. But engineers had to scrap their plan to work on the tunnel from the inside when divers found just 25cm of mud separating the bricks of the tunnel roof from the Thames.

Instead, Crossrail have built dams to hold back the water from the tunnel while they take the roof off and widen and deepen it. This technique of digging from the surface rather than tunnelling laterally is similar to what was done in the 1870s.

After the tunnelling concludes, some of the tunnel boring machines, which each cost £10m, will be lifted out in pieces. But where there is no nearby shaft to the surface that can't happen.

"Then it's not cost effective to dismantle the machine underground and it's quite risky for the workforce to do that," says Andy Alder. "So in those cases we would look to bury the TBM and leave it underground forever - we strip out all the valuable components, but the basic shell of the machine we'll leave underground."

Phyllis's lead miner Jim Gagan feels he is leaving a part of himself underground too.

"I can touch the wall, or I can touch the back of a segment and I know that I could be the last man that touches that forever and a day," he says.

You can listen to Discovery on the BBC World Service. The episode about Crossrail will be broadcast on 5 August at 10.30 - listen live or get the Discovery podcast.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external