Why do people still fly the Confederate flag?

- Published

A row has erupted in Virginia over a proposal to fly a huge Confederate flag outside the state capital, Richmond. One hundred and fifty years after the Civil War, the flag can still be seen flying from homes and cars in the South. Why?

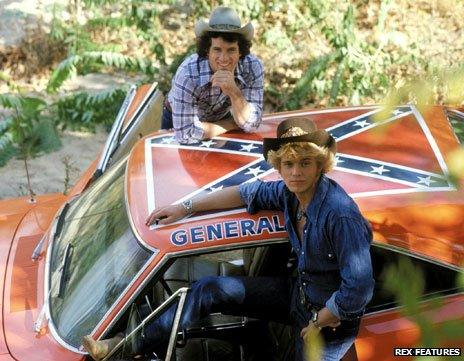

For millions of young Britons growing up in the early 1980s, one particular image of the Confederate flag was beamed into living rooms across the UK every Saturday evening.

The flag emblazoned the roof of the General Lee, becoming a blur of white stars on a blue cross when at breathtaking speed, the Dodge Charger took the two heroes, Bo and Luke Duke, out of the clutches of the hapless police in The Dukes of Hazzard.

Thousands of miles from the fictional county of Hazzard in Georgia, it seemed like an innocent motif but in the US, the flag taken into battle by the Confederate states in the Civil War is politically charged - not a week goes by without its appearance sparking upset.

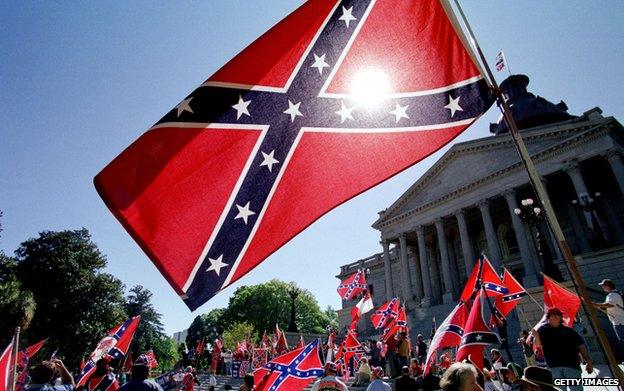

Recently, there's been a row in Texas over car licence plates bearing the flag, a man arrested after shouting abuse while waving it at a country music concert, and the ongoing fallout from South Carolina flying the flag in front of the State House.

Now plans by a heritage group, the Virginia Flaggers, to erect a large Confederate flag on a major road outside Richmond has drawn considerable fire from critics who say it's a symbol of hate.

That's not true, says Barry Isenhour, a member of the group, who says it's really about honouring the Confederate soldiers who gave their lives. For him, the war was not primarily about slavery but standing up to being over-taxed, and he says many southerners abhorred slavery.

"They fought for the family and fought for the state. We are tired of people saying they did something wrong. They were freedom-loving Americans who stood up to the tyranny of the North. They seceded from the US government not from the American idea."

He displays a flag on his car but lives in a street where the flying of any flags is not permitted. They are a dwindling sight these days, he thinks, because people are less inclined to fly them in the face of hostility - monuments honouring southern Civil War generals are, he says, regularly vandalised.

Denouncing the "hateful" groups like the Ku Klux Klan who he says have dishonoured the flag, he adds that people should be just as offended by the Union Jack, the Dutch flag or the Stars and Stripes, because they all flew for nations practising slavery.

Annie Chambers Caddell sparked outrage when she decided to hang a Confederate flag from her porch

Others strongly disagree with his analysis. African Americans, especially older ones, are traumatised when they see the flag, says Salim Khalfani, who has lived in Richmond for nearly 40 years and thinks it risks making the city look like a "hick" backwater that is still fighting the Civil War.

"If it's really about heritage then keep the flag on your private property or in museums but don't mess it up for municipalities and states who are trying to bring tourists here because this will have the opposite effect."

African-American author Clenora Hudson-Weens saw people waving the flags on the street in Memphis a few weeks ago. "I just said to them 'This is 2013' and they just smiled. I personally believe in some traditions but this is a tradition that is so oppressive to blacks. I wouldn't be proud waving a flag that has an ambience of racism and negativity."

Many Americans will be familiar with the arguments on either side but perhaps not with the convoluted origins of the flag itself.

The flag seen today on houses, bumper stickers and T-shirts - sometimes accompanied by the words "If this shirt offends you, you need a history lesson" - is not, and never was, the official national flag of the Confederacy.

The design by William Porcher Miles, who chaired the flag committee, was rejected as the national flag in 1861, overlooked in favour of the Stars and Bars.

It was instead adopted as a square battle flag by the Army of Northern Virginia under General Lee, the greatest military force of the Confederacy. It fast became such a potent symbol of Confederate nationalism that in 1863 it was incorporated into the next design of the national flag, which replaced the hated Stars and Bars.

The saltire - or diagonal cross - on the battle flag is believed to have been inspired by its heraldic connections, not any Scottish ones.

How a flag was born

The first national flag of the Confederacy was the Stars and Bars (left) in 1861, but it caused confusion on the battlefield and rancour off it

"Everybody wants a new Confederate flag," wrote George Bagby, Southern Literary Messenger editor. "The present one is universally hated. It resembles the Yankee flag and that is enough to make it unutterably detestable."

Its replacement was nicknamed the Stainless Banner (centre) and it incorporated General Lee's battle flag, designed by William Porcher Mills

A third national flag, nicknamed the Bloodstained Banner (right) was adopted in 1865 but was not widely manufactured

After the war, the battle flag, not any of the national ones, lived on

So has the flag historically been more about slavery or heritage?

You could say that both sides are correct if you look at how the flag has evolved, says David Goldfield, author of Still Fighting The Civil War.

When the Confederacy debated the adoption of a new flag in Richmond in 1862, it was clear this was to be a symbol of white supremacy and a slavery-dominated society, he says.

After the war, the flag was primarily used for commemorative purposes at graves, memorial services and soldier reunions, but from the perspective of African Americans, the history and heritage that they see is hate, suppression and white supremacy, says Goldfield, and the historical record supports that.

"On the other hand, there are white southerners who trace their ancestors back to the Civil War and want to fly the flag for their great-grandfather who fought under it and died under it." And for them, it genuinely has nothing to do with racism. However, he thinks they should respect the fact it does cause offence and not fly it in public.

The flag is commonly seen at Nascar races

The flag wasn't a major symbol until the Civil Rights movement began to take shape in the 1950s, says Bill Ferris, founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, It was a battle flag relegated to history but the Ku Klux Klan and others who resisted desegregation turned to the flag as a symbol.

He likens it to the swastika but others see it very differently. Indeed, the flag has been compared to a Rorschach blot because it means several things at all at once, depending on who is looking at it.

"All symbols are liable to multiple interpretations but this is unique in its power and ability to inflame passions on all sides, and the volume of interpretations and preconceptions about it make it unique in American history," says John Coski, author of The Confederate Battle Flag: America's Most Embattled Emblem. He has even seen it displayed in Europe, where it has become shorthand for "rebel".

Since attempts by campaigners in the 1990s to remove the flags from public buildings, he thinks the issue has died down in the US. In 2001, Georgia changed the 45-year-old design of its state flag after pressure to remove the Confederate symbol.

Although the number of incidents is diminishing it's not going away, he says, because it just takes a couple of well-publicised episodes to get it back on people's radars, and feelings inflamed.

"We can all write the script ourselves - they will say this and they will say this." It's a predictable pattern, he adds.

"I think it will die out," says Ferris, who thinks flag-wavers feel like an embattled minority. "The south is changing, with the growth of Hispanics and Asian and a growing black population, and you can be sure that the Confederate flag has no place in their world."

The South, he says, needs a new emblem to reflect its changing character.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external