How do people forgive a crime like murder?

- Published

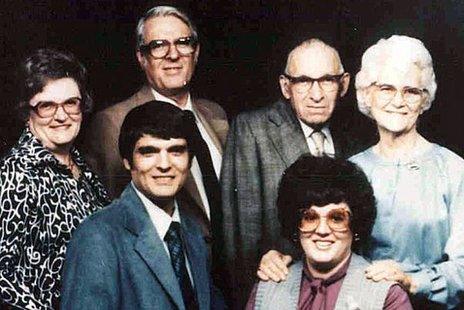

Ruth Pelke (left) and the woman who murdered her, Paula Cooper (right)

The moment when a murderer is released from prison can be a traumatic one for the victim's family. But for American Bill Pelke the release of his grandmother's killer this year was different - he has not only forgiven her, he wants to help her start a new life. How are people able to forgive a crime like this?

It was late afternoon in May, 1985. Bill Pelke was at his girlfriend's house when he received a phone call from his brother-in-law.

"Nana had been stabbed to death," says Pelke. "The house had been ransacked. My father found the body."

His grandmother, Ruth Pelke, a 78-year-old Bible teacher, had been murdered at her home by four teenage girls.

The following day Pelke was at the hairdresser's, getting ready for the funeral, when he heard news of their arrest.

"I was shocked that four girls that young could be involved," he says. "I had kids the same age."

Three of the girls received lengthy prison sentences, ranging from 25 to 60 years. One of them, Paula Cooper, was seen as the ringleader and sentenced to death on 11 July 1986.

Pelke attended the trial as well as the sentencing of Paula Cooper, and at the time he felt the death penalty was an appropriate sentence.

But 18 months after his grandmother's death he started to reconsider.

"I was envisioning Nana butchered on the dining-room floor - the dining-room my family used to go to every year to gather for Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas. I couldn't stand thinking about it," he says.

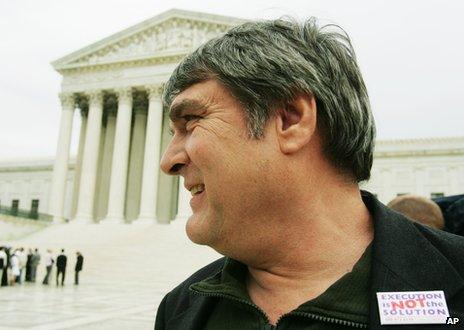

Bill Pelke now campaigns against the death penalty for teenagers

Pelke started wondering what impact the death penalty for Cooper would have on her family, especially Cooper's grandfather who attended the trial and who Pelke had seen break down in tears when the sentence was handed down.

"My grandmother would not have wanted this old man to witness his teenage grand-daughter die," he says. "Everyone in north-west Indiana wanted Paula Cooper to die - Nana would have been appalled by the anger."

Pelke became increasingly convinced that his grandmother - a devout Christian - would have felt love and compassion for Cooper and would have wanted someone in the family to feel the same.

"I felt like it fell on my shoulders," he says. "When I was touched by compassion and forgiveness, I no longer pictured Nana dead but alive. Something terrific had happened inside of me."

Pelke says his decision to forgive brought him "tremendous healing".

But some members of his family struggled to accept his decision. It was particularly hard for Pelke's father, who had found the dead body of his mother and testified in court.

"He was not happy," he says. "It caused a tense relationship for years."

Despite the disagreement Pelke says he never changed his mind about forgiving Cooper.

"I knew I was doing the right thing, and later my father forgave me for forgiving Paula Cooper. He came a long way."

Pelke decided to pursue a meeting with Cooper in prison, but it was eight years before the authorities allowed them to meet - on Thanksgiving 1994.

"I walked in and gave her a hug," says Pelke. Then he looked Cooper in the eyes and told her that he had forgiven her.

Despite corresponding weekly and making 15 prison visits, Pelke has never asked Cooper about the crime.

"I know there is no good answer," he says.

The Pelke family shortly before the murder - Ruth (top right) and Bill (front left)

Bringing perpetrators and victims together can have benefits for both sides, says Howard Zehr, a Professor of Restorative Justice at the Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia, who has facilitated hundreds of such meetings.

As well as making the offender see the impact on people who have been hurt, the meetings often reduce the victim's trauma - and victims of severe violence regularly report a high level of satisfaction, he says.

"Victims are often stuck in their experience," says Zehr. "The meetings enable them to get answers and let go."

One of the most memorable meetings for Zehr was when a man who had committed 14 sexual assaults on women under 18, met his last victim.

"She met him and confronted him with the question 'How could you do this to me? You stole my childhood,'" remembers Zehr.

"The perpetrator said he came to realise for the first time what he had done. He had some insight," he says. "The woman didn't forgive him, but it was no longer the dominant experience of her life."

But Zehr strongly urges victims who want to pursue a meeting with the offender to seek the support of a facilitator, who can act as a "gatekeeper".

"Success depends on the level of preparation on both sides, sometimes it can take up to a year," he says.

"As a facilitator, I speak to both sides ahead of the meeting, I try and make them aware of the dynamics of trauma, as well as the possibility that their expectation might not be fulfilled. The perpetrator might not be able to answer questions."

Seventeen years after the brutal death of her daughter, Texan Linda White still has questions about the day she was killed.

Cathy White was pregnant with her second child when she was murdered

In November 1986 Cathy White, a 26-year-old mother who was pregnant with her second child, was abducted, raped and killed by two teenage boys.

Like Pelke, White eventually met and forgave one of her daughter's killers, but the process took much longer - almost 15 years.

Following her daughter's death White says she felt not only an enormous amount of grief but also a sense of not fully being in charge of her life.

"For a parent, losing a child feels like the most unfair, wrong thing in the world. It's upside down. The world didn't feel as friendly as it once was - and I felt I had little power."

She joined victim support groups, but found scant comfort in them.

"Nobody moved, everyone stayed the same," she says. "People stayed angry. I didn't want to be five years down the road and be the way they were - full of bitterness. I didn't want to be grieving for the rest of my life and think of it as ruined."

White, who had two sons and was now looking after her five-year-old grand-daughter, wanted to get on with her life. She says if she had given in, she would have felt like she had killed herself - not literally but in her mind.

She started taking her granddaughter to counselling. It was that experience that prompted her to study psychology, and later to become a grief counsellor.

White says that by helping people cope with loss and grief she managed to gain back some control in her life. In January 1997, she decided to start teaching in prison - an experience she loved, and which "gave her healing", she says.

Linda White says forgiving her daughter's killer has helped her move on

"I do believe people are more than the worst thing they have ever done. A lot of what we do while people are incarcerated is dehumanising, degrading and demoralising," she says. "I was trying to put some humanity back in."

Her experience working with offenders in prison led to an even more radical decision. White decided to meet one of her daughter's murderers, Gary Brown.

"I didn't know what he looked like. I had never ever looked at a picture of him," she says.

She sought the encounter to test whether she would be able to be compassionate towards him.

"I wanted the person I had become to meet with the person he had become."

White and her 18-year-old granddaughter Ami met Brown in prison in 2001 for a conversation that lasted all day.

"I was astonished by how young and vulnerable he looked. It was very emotional," she says.

For White one of the most difficult moments of the encounter was hearing Brown's account of what happened to her daughter before she died.

"I was spellbound when he started talking. Gary told us exactly what happened, how it happened, the progression of it. That part was hard to hear, but I was ready for it."

Brown also told the Whites that Cathy's last words to him before she was shot dead were, "I forgive you and God will too."

"I was blown away when he told me," says White.

White has stayed in touch with Brown, who is now out of prison and on probation. The last time she heard from him was around Christmas - when he texted her.

While on probation Brown is not allowed to contact the Whites, but earlier he had approached Linda about eventually speaking in public together.

"We talked about addressing children and teenagers that are going down the wrong road," she explains. "I hope that in the future, when he is allowed to move around freely, we will be able to do that together."

There are also things she still wants to ask Brown about that evening her daughter was killed.

"I still wonder how the evening descended into violence. Why they raped her. The guys had no records of previous violence," she says. "When I am ready to see him, I want to ask Gary face-to-face."

Despite that last lingering question, White thinks meeting Brown has kept her sane.

"If you let grief take over your life, it's as if the offence continues over and over again. It turns you angry and bitter. It's almost like the only relationship you have left with your lost loved one is through the bitterness. People cling to that - because naturally they don't want to let go," says White.

"Sometimes people feel that moving towards resolution of their grief - or healing in any way - is a disloyalty to the person that was killed. But it's not."

Like Linda White, Bill Pelke wants to stay in touch with Paula Cooper, who was released in June, her death sentence having been set aside and her subsequent prison term greatly reduced due to her behaviour as a prisoner.

This is Paula Cooper last year - soon before her release from prison

While she was in prison Pelke had been campaigning for her to be released.

"I am very happy she is free. I was looking for this day for several years," he says.

Pelke knows that there are a lot of people who don't understand him. But for him the decision to forgive changed his life, and he has never looked back.

He now wants to help Cooper adapt to modern life.

"She has never seen a cellphone or a computer. She has never written a cheque, applied for a job or had a bank account. It's going to be very difficult for her, in fact she told me she was scared."

Cooper is currently staying in a safe house as part of her transition from prison to life outside and has been advised against contacting Pelke just yet.

But Pelke says that when Cooper is eventually allowed to meet him, he will take her out for a meal and some shopping - to buy, among other things, a computer.

"If you hang on to anger and the desire for revenge, eventually it becomes like a cancer and it will destroy you," he says. "I did the right thing."

Bill Pelke was interviewed on the BBC World Service programme Newshour, which airs every day at 12:06, 13:06 and 20:06 GMT