Unlocking the secrets of the Elephant Man

- Published

The Elephant Man, Joseph Merrick, was an object of curiosity and ridicule throughout his life - studied, prodded and examined by the Victorian medical establishment. Now, 123 years after his death, scientists believe his bones contain secrets about his condition which could benefit medical science today.

Joseph Merrick began to develop abnormally from an early age, eventually being gawped at by Victorian circusgoers and examined by inquisitive doctors. The cause of his malformed head, curved spine, "lumpy" skin and overgrown right arm and hand has never been definitively explained.

Ironically, it is the medical preservation of Merrick's skeleton that is now causing the greatest problems in unlocking his body's secrets.

"The skeleton, which is well over a hundred years old now, is actually very clean," says Prof Richard Trembath, vice-principal for health at Queen Mary University of London, and the custodian of Merrick's body.

"This represents a significant problem. On a number of occasions over the years the skeleton has been bleached during the preservation process. Bleach is not a good chemical to expose DNA to. It gives us an added problem in trying to extract sufficient quantities of DNA in order to undertake sequencing."

The hope is, though, that DNA can be extracted which will determine once and for all exactly what genetic condition he suffered from.

There have been several theories. For many years it was thought he had neurofibromatosis type 1, but in more recent years doctors have come to believe he had a condition known as Proteus Syndrome, or possibly a combination of both.

A team of geneticists from Queen Mary University of London, King's College London, and the Natural History Museum are currently working on techniques to extract DNA from similar age bones which have also been bleached before beginning work on Merrick's skeleton. They are anxious to keep any further damage to the bones to a minimum.

Bleach is sometimes used in labs to remove traces of DNA, so in many ways it is the worst possible thing to do to bones if the hope is to extract genetic information.

The genetic condition of Richard III's remains - buried for hundreds of years below a car park in Leicester - is actually better than those of Merrick.

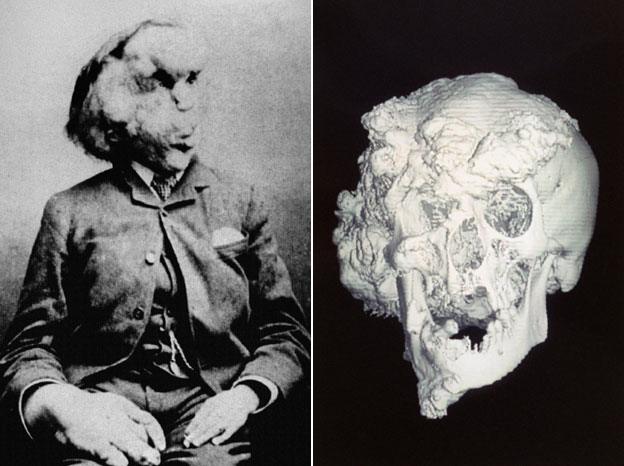

His extreme deformity is obvious from his skeleton, but confined to parts of his body. His skull has large growths of bone at the front of his temple and on the right side.

His right arm and hand is far bigger than his left, which appears normal, and his right femur (upper leg bone) is much bigger and thicker than the left. His spine is also badly curved, causing the whole body to be hunched.

"When Merrick was being formed in his mother's womb it is highly likely that a genetic alteration occurred, but not until after the sperm and the egg had come together - probably at a stage when there were a number of cells, only some of which have gone on to contribute to his problems," says Trembath.

The skeleton is kept under lock and key in a small museum in the medical school at the Royal London Hospital, and is not normally on public display. It is the same hospital where Merrick spent his later years as a friend and patient of the prominent Victorian surgeon Frederick Treves, and the place where he died at the age of 27 in April 1890.

According to Treves, Merrick died from a dislocated neck when he lay down to sleep, due to the huge weight of his head.

Joseph Merrick photographed (left), and his skull

The team of geneticists extracting the DNA is being led by Dr Michael Simpson from King's College London. In his lab he has been working on segments of bone to develop new techniques for obtaining genetic information from badly bleached fragments.

The team has been successful in obtaining DNA, but is still working on methods of "cleaning" the badly damaged DNA sufficiently to obtain a complete genetic sequence.

This is important in order to see exactly where in Merrick's genetic code the mutations appear. To complicate matters further, Simpson believes the bones have also been waxed, which might also affect the DNA.

"There will be some challenges," admits Simpson, in something of an understatement, "But with some further optimisation I am confident that we will be successful. We should have a good chance of sequencing his genome."

The technique involves drilling out a small quantity of bone powder, treating it with detergents and enzymes to extract the protein, and then removing the DNA.

When work starts on Merrick's skeleton, the intention is to make comparisons between the DNA in distorted bone areas and the DNA in normal bone. Two main areas have been identified for drilling - the inside of his skull and the root of one of his teeth.

Apart from scientific curiosity in his medical condition, Trembath believes the results could help modern medical science and its knowledge of cell division.

Michael Simpson holds a femur of a similar age to Merrick's

"This is very significant overgrowth of tissue," he says while examining the growths on the skull. "The understanding of the regulation of cell growth is one of the most fundamental things that we need to understand. It sits behind the development of tumours and we need to understand more about how tumours develop."

He points out that Merrick himself was keen to help the Victorian doctors with their scientific investigation. More than a century on, the work continues.

"I have a sense that he is an ever willing partner in trying to help us get there. This is one of the most extreme forms of overgrowth that has ever been seen, and so there is a unique opportunity to gain some fundamental insights into human biology, and Merrick knew he was sitting on that kind of information."

Listen to Andrew Bomford's report on Radio 4's PM programme at 17:00 BST on 29 August

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external