9/11: The man who 'plotted' America's darkest day

- Published

Relatives of the dead gathered in New York to mark the 12th anniversary of 9/11. Meanwhile, 1,400 miles away, the man who says he masterminded the attacks awaits his trial.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed walked into a courtroom in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, one morning in August. The door stayed open for a moment and sunlight fell across the floor.

Laura and Caroline Ogonowski watched him from a gallery behind three plates of glass. They are daughters of John Ogonowski, the 50-year-old pilot of American Airlines Flight 11, the first plane that crashed into the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001.

Tom and JoAnn Meehan were also there. They lost their daughter, Colleen Barkow, 26, in the World Trade Center. Rosemary Dillard's husband, Eddie, 54, died in the jet that crashed into the Pentagon.

The room was quiet.

Mohammed adjusted his turban with both hands, as if it were a hat. He was short and overweight, and he walked in a jerky manner - like a Lego Star Wars character, someone in the gallery remarked later.

"He has a high voice," says the court illustrator, Janet Hamlin. "I expected a baritone. Darth Vader."

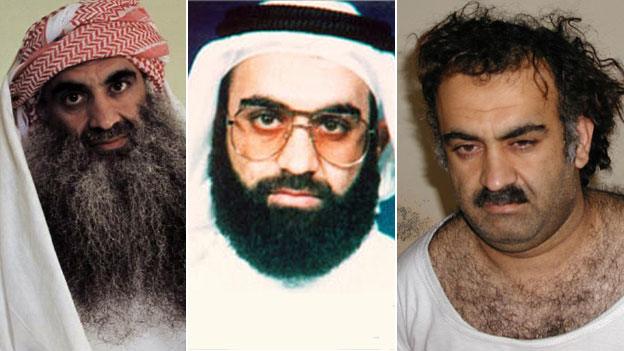

Mohammed and the other four defendants, Walid bin Attash, Ammar al-Baluchi (also known as Abd al-Aziz Ali), Ramzi Binalshibh and Mustafa Ahmed al-Hawsawi are accused of helping to finance and train the men who flew the jets into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field.

They face charges that include terrorism and 2,976 counts of murder, and they could be executed.

Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, Waleed bin Attash, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi, Ramzi Binalshibh

US v Mohammed has been described as the trial of the century. At the centre of the drama is the world's most notorious al-Qaeda member.

"If we were a different country, we might have taken him out and shot him," says a spokesman for the Guantanamo detention facility, Capt Robert Durand, during the hearing.

The legal proceedings against Mohammed provide a chance for people in the courtroom and others to observe him and also to deepen their understanding of al-Qaeda. In addition, his public image reflects the different ways that people have looked at al-Qaeda over the years.

"History consists not only in what important people did," wrote David Greenberg in Nixon's Shadow: The History of an Image, a book that looks at the ways that President Nixon has been perceived over the years, "but equally in what they symbolised".

Mohammed, a 48-year-old mechanical engineer, is thought to be a mastermind of al-Qaeda violence and a brilliant, bloody tactician. He was captured in Pakistan on 1 March 2003, less than three weeks before US troops entered Iraq.

People in the US were on edge. They wondered when al-Qaeda would strike again. Meanwhile Pentagon officials were preparing for a military intervention in Iraq. Bush administration officials spoke of a link between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda. "The evidence is overwhelming," Vice-President Dick Cheney said in a television interview, external.

Like other widely-held ideas about al-Qaeda, this one turned out to be untrue.

Twelve years after the attacks, the Obamas attend a 9/11 memorial in Washington

In 2009, US Attorney General Eric Holder announced that Mohammed would be put on trial in New York, setting off a political firestorm. The controversy reflected an ongoing and emotionally charged debate regarding national security - is al-Qaeda a serious threat?

President Barack Obama and his deputies were trying to move the nation beyond an age of fear. Not everyone believed the threat had diminished, though.

Conservatives were outraged, saying Mohammed was a danger to Americans and should be tried in a military court. Holder eventually gave up his plans, and prosecutors in Guantanamo filed charges against Mohammed in 2011.

Since that time Mohammed has in the public eye become a comical figure, a man who attempted to re-invent the vacuum cleaner while in prison. "A shoo-in for the Gitmo science fair", said late-night television host David Letterman.

Meanwhile Mohammed and the other defendants were supposedly reading EL James' 50 Shades of Grey. This turned out to be a rumour.

Nevertheless the attempts to ridicule him show how the public's view of al-Qaeda has softened. An essayist for the Washington Post, external called him "the Kevin Bacon of terrorism", alluding to a parlour game, Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, in which players find different ways Bacon is connected with other actors.

Once an icon of terror, Mohammed has been turned into an object of derision.

Mohammed's image has also gone through a transformation within al-Qaeda. He was "popular" in the 1990s, according to the authors of The 9/11 Commission Report. (It was compiled by members of a bipartisan federal commission chaired by a former New Jersey governor, Thomas Kean, and a former Indiana congressman, Lee Hamilton.)

Mohammed's colleagues described him as "an intelligent, efficient, and even-tempered manager", wrote the authors.

His reputation "skyrocketed" after 9/11, says Marc Sageman, a former CIA officer and the author of Understanding Terror Networks. When Mohammed was arrested, he became a "martyr". He can no longer communicate with al-Qaeda, though, and consequently has little influence on the organisation.

Attorney General Eric Holder said that Mohammed should be tried in a civilian court in New York

The legal proceedings against him are unfolding in a corrugated-metal building in a compound known as Camp Justice. Prosecutors want the trial to start in one year. Defence lawyers baulk, saying that it will take much longer to resolve the legal issues surrounding the case.

Mohammed's lawyers say that he was tortured while he was held in CIA-run "black sites", reportedly in Poland and Romania. The evidence against him is tainted by the brutality of these interrogations, the lawyers say, and therefore the charges should be dropped.

On a more fundamental level the defence lawyers say that the military commissions are not legitimate. The court, they claim, favours the prosecution.

Mohammed, suntanned and wearing glasses, rifled through legal papers in the courtroom during a hearing last month. He had an e-reader, and he seemed comfortable in the courtroom - and with his fate.

He is a "death volunteer", a capital defendant who wants to become a martyr, at least that is what he claimed in 2008. He has not entered a formal plea - though he has talked at length about his role as an al-Qaeda mastermind. The court treats the situation as if he has pleaded not guilty.

Al-Qaeda commanders aim to broadcast a message, whether through violence or other means. One of their most important weapons is propaganda.

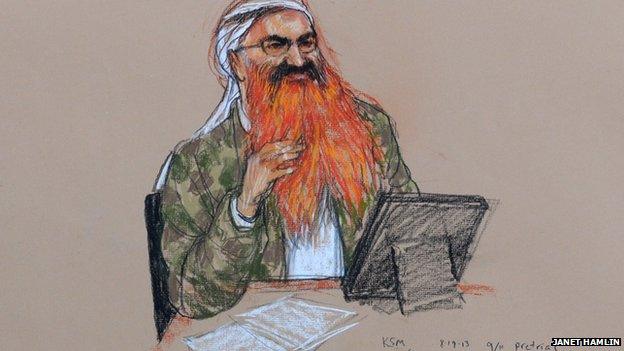

As a PR director for al-Qaeda, Mohammed attempts to shape his own image and that of al-Qaeda. He dyed his beard reddish-orange with berry juice, and he wore a tunic and a military-style camouflage jacket.

Wearing "camo" sends a message - he is a soldier.

He grew up in a religious family in a suburb of Kuwait City. He is a citizen of Pakistan, though, and his relatives come from Baluchistan.

At age 11 or 12 he started watching Muslim Brotherhood programmes on television. Later he went to youth camps in the desert - and became interested in jihad.

His family sent him to the US to study. After earning an engineering degree from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in 1986, he fixed hydraulic drills on the front lines in Afghanistan, according to a December 2006 US defence department report., external

At the time he was helping the US-backed mujahedeen. He says he later became "an enemy of the US", according to the defence department.

"By his own account", wrote the authors of the 9/11 Commission Report, he hated the US not because of anything he saw during the years he lived in the US - but because of US policies towards Israel.

By this time the Muslim Brotherhood brand of jihad was too tame for him. He wanted violence, according to government documents. He chose targets for the 2001 attacks based on their capacity to "awaken people politically".

He had originally planned for the hijacking of 10 commercial jets, according to the authors of the 9/11 Commission Report. He wanted to land one of the jets himself.

"After killing all adult male passengers on board and alerting the media", he would then "deliver a speech excoriating US support for Israel, the Philippines, and repressive governments in the Arab world."

"This is theatre, a spectacle of destruction with KSM as the self-cast star - the super-terrorist," wrote the authors.

Several months after the attacks, the Wall Street Journal's Daniel Pearl arranged to interview a militant, Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, a former London School of Economics student, in Karachi. It was a ruse - Pearl was kidnapped and beheaded.

Mohammed says that he held the knife, "with my blessed right hand". He made this comment in court, testimony of how he had decapitated Pearl.

A memorial service was held for Daniel Pearl in New Delhi in February 2002

Mohammed spoke to another journalist about the 9/11 attack. "The attacks were designed to cause as many deaths as possible and to be a big slap for America on American soil," Mohammed told the journalist at a hideout in Pakistan.

Mohammed spoke proudly of his leadership role in the attacks, and an account, external of the conversation was published in the Sunday Times in September 2002.

Seven months later, Mohammed was seized in Rawalpindi and then taken to Poland. A group of men, wearing black masks "like Planet-X people", waited for him at an airport, he says, according to a leaked copy of an International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) report, external.

He was taken to a cell, "about 3m x 4m with wooden walls", in a CIA black site. During the interrogations, he worked as a propagandist, offering some insight into al-Qaeda, and a lot of misinformation.

"I later told the interrogators that their methods were stupid and counterproductive," he said, according to the ICRC report. "I'm sure that the false information I was forced to invent in order to make the ill-treatment stop wasted a lot of their time and led to several false red-alerts being placed in the US."

He had lied, exaggerating the threat that al-Qaeda posed to Americans. On other occasions he has been a stickler for accuracy. He is something of a control freak - and tries to ensure that messages are transmitted properly.

In military hearings, he corrected the spelling of his name.

Through his lawyer, he chided Hamlin for a sloppy drawing. "I was like, 'Oh, no, he's right,'" she says. She fixed his nose, working in pastel.

Mohammed also mentioned at one of the hearings, external that the journalist who had interviewed him for the Sunday Times had got things wrong.

"You know the media," he said.

Mohammed said that his nose was poorly drawn in the original version of this illustration

He does not refute previous statements about his role in the 2001 attacks, though. Indeed, he has reinforced them.

"I was responsible for the 9/11 operation, from A to Z," he said in a March 2007 hearing. He described himself and other al-Qaeda members as "jackals fighting in the night".

Still, he says he feels remorse. "I don't like to kill people," he said. "I feel very sorry there had been kids killed in 9/11."

In the mornings during the August hearings he was escorted to the courthouse from his holding cell, "a little, one-person supermax", says a military official. Barbed wire stretched like a giant Slinky along the top of a fence. Green sand bags were scattered around, along with Joint Task Force barricades marked "restricted area".

Mohammed walked past an army officer with handcuffs tucked in his waistband. Soldiers with Internal Security badges hovered near the door.

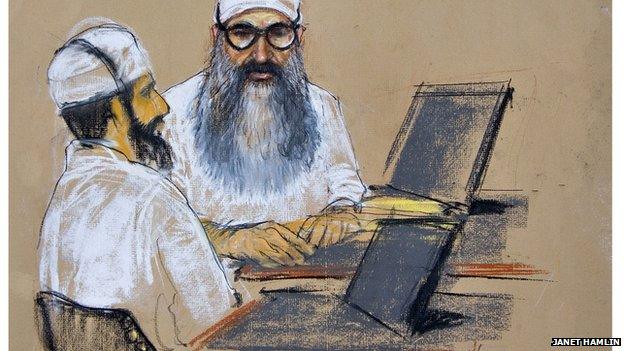

Illustrator Janet Hamlin, shown with a sketchpad, and family members of victims sit in a gallery

Mohammed took off his glasses and put them on the table. He had a prayer blanket folded over the back of his chair, and a box decorated with an American flag is on the floor.

He is "well-travelled", says one of his lawyers. According to government accounts, he has spent time in Qatar, Indonesia, India, Malaysia and other countries.

The authors of The 9/11 Commission Report described him as "highly educated and equally comfortable in a government office or a terrorist safehouse".

During the hearings he expressed sympathy to his lawyers because they have to spend time away from their families. "He's a very gracious individual," says one lawyer.

Dillard and the others who lost family members in the 2001 attacks sit behind sound-proof glass. They listen to an audio feed that is delayed by 40 seconds so officials can block statements that are classified. This includes information about the interrogations.

For a year or so after the 2001 attacks, US officials acted as though Mohammed and other suspects had super-human intelligence and strength, as if only individuals who were larger than life could carry out the attacks.

Before detainees arrived at Guantanamo, for example, Richard Myers, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff "warned that any lapses in security might allow the detainees, endowed with satanic determination, to 'gnaw hydraulic lines in the back of a C-17 to bring it down,'" wrote Karen Greenberg in her book The Least Worst Place: Guantanamo's First 100 Days.

This mythology can still be seen in the courtroom. Steel chains, each comprised of 12 links, were fastened to the floor near the detainees' chairs. Each of the chains was arranged in a straight line, and they were installed so that they could be used to restrain unruly detainees. The chains were heavy and thick, sturdy enough for a "super-villain", as one military official tells me.

In the courtroom Mohammed waved over a legal assistant, a woman with blonde hair tucked under a headscarf. He sliced his hand through the air. He had surprisingly thin wrists, and his "blessed right hand" was pale.

It is hard to imagine that he once cut off Pearl's head. Later I mentioned this to one of Mohammed's lawyers. He was sitting at a picnic table outside the courthouse, near a metal sign that said: "No classified discussion area".

"It's inconceivable that this person could do that," said the lawyer, nodding. "That sets up a number of scenarios for us to investigate."

Mohammed has spoken openly about al-Qaeda operations during his confinement at Guantananmo

The lawyer and his colleagues are exploring possibilities for their clients' defence.

Sitting at the picnic table, the defence lawyer made a case for Mohammed's innocence - he confessed to crimes he did not commit while "under the tender mercies of the CIA".

I pointed out that he has spoken freely about his role in the crimes - frequently, and with journalists and others who do not work for the CIA. I mention the beheading.

"You keep going back to that," said the lawyer, looking impatient. He said that Mohammed is not being charged with Pearl's murder.

Then he changes tactics. He says that if Mohammad had carried out these crimes, he would have had a reason.

Mohammed is a principled man, the lawyer explained. Someone like him might commit crimes if he believed they were in the service of a greater good. Moreover these acts would carry a personal cost.

"You're sacrificing your life, your family and any future happiness for what you perceive as the good of the defence of your community," said the lawyer.

Even if Mohammed did plan the terrorist attacks and murder Pearl, the lawyer said, these acts do not make him special. "You may have had the opportunity of being in a press conference with George W Bush. He's responsible for about 5,000 deaths."

Many people would like to close the chapter on al-Qaeda and the global war against terrorism. Yet not everyone is ready to move on - or has that luxury.

Dillard said that she wants both the defence and the prosecution to "be very, very careful to maintain the integrity of the trial - so that there's no space for an appeal".

On the last day of the hearing, Dillard walked to a makeshift media-operations centre in an aeroplane hangar. In front of a microphone, she talked about her husband - and about Mohammed and the other accused men.

"I don't want them to ever see the sunshine," she said. "I don't want them to have fresh wind hit their face." She walked back to the side of the room and stood with others who have lost family members.

The next pre-trial hearing at Guantanamo starts on Monday.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external