The great Cold War potato beetle battle

- Published

In 1950 the East German government claimed the Americans were dropping potato beetles out of planes over GDR fields in an attempt to sabotage their crops. Was it true, or an example of Cold War propaganda?

On 23 May 1950, farmer Max Troeger noticed two American planes flying over his fields in the East German village of Schoenfels bei Zwickau.

The next morning - according to an East German government leaflet - he was shocked to discover that his fields were covered with Colorado potato beetles, an insect which can devastate potato crops.

First described in 1824, the beetle had presented a major threat to European crops when it had first arrived with potatoes imported from the US in the late 19th Century.

Was America deliberately dropping these beasties over the socialist East German state to sabotage its harvest and undermine its post-war reconstruction?

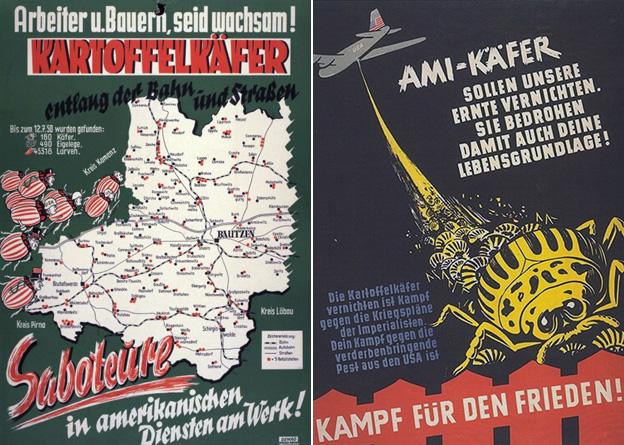

The East German press reported a number of other cases in which planes flying overhead had been followed by a plague of potato beetles. Politicians raged against the "six-legged ambassadors of the American invasion" and a government report described "a criminal attack by American imperialist warmongers on our people's food supply".

So the country began to mobilise against the enemy insects.

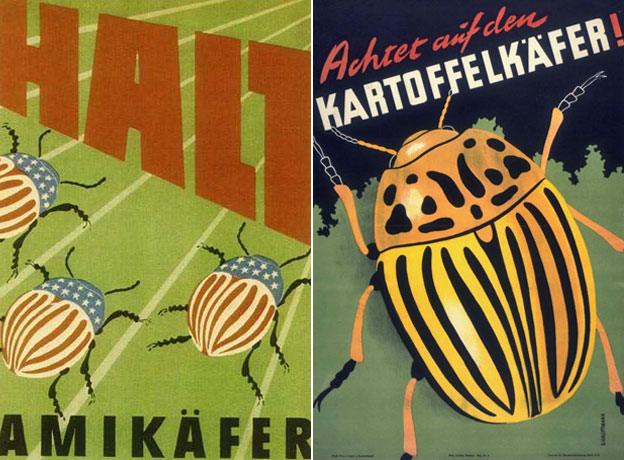

There was a huge propaganda campaign - leaflets, posters, stories in the press - depicting the potato beetles as tiny American soldiers in army boots or helmets. They were called Amikafer - Yankee beetles.

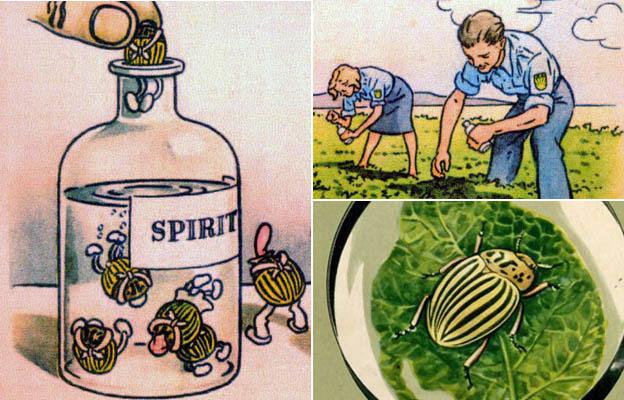

Children all over East Germany were sent out to collect the beetles after school.

"We were told that potato beetles were pests, and that they were eating our fields bare," says Ingo Materna, who was 18 at the time.

"We would go down the rows of potatoes and everyone would try to pick up as many beetles as they could, maybe 20 or 25 in a day. And then we would put them in pots or little glass jars and they would be taken away and destroyed.

"The really dangerous ones were the larvae, because they eat the most," says Materna.

"They were sort of fleshy and soft, and we had to pick them up with our fingers - we didn't have tweezers or rubber gloves.

"The girls in particular didn't like it… We didn't want to touch them either, but what could we do?"

The East German government issued a number of books and leaflets aimed specifically at schoolchildren

Colorado beetles had already been common in Germany before the war, says Erhard Geissler, an expert in biological warfare at the Max Delbruck Centre for Molecular Medicine, who has researched the history of the pests.

And in 1950, there were indeed many more of them in the fields. But, there were plenty of other reasons why that might have been the case, says Geissler.

"There was not enough pesticide available because not enough was being produced, and what was produced was mainly sent straight to the Soviet Union.

"There was not enough technical advice on pesticides, and motivation among farm workers was also very low at that time - a lot of male workers who had been soldiers, were still in the Soviet Union."

Many East Germans did believe that the Americans were to blame, however.

"I found that a majority of older people, particularly in rural areas, remembered it had been the US imperialist who spread the beetles from the aeroplanes," says Geissler.

Eighteen-year-old Ingo Materna, had a different view. "We didn't take it seriously at all," he says.

Even though he and his friends were dutifully picking the beetles up, they weren't convinced by the story of the capitalist plot.

"The idea that the Americans were dropping them - of course, that was nonsense."

This was the period of the Cold War, a time of heightened mistrust between East and West.

For Materna - who shared his memories as part of an oral history project, Memory of the Nation - the government was seizing every opportunity to accuse the Americans of bad behaviour.

"Some of the stories were probably true and some of them definitely weren't," he says. "This beetle story was one of the ones that wasn't."

Whatever the origin of the beetles, they did pose a serious threat to East German crops.

"Potatoes were the main thing we had to eat in East Germany at the time," remembers Geissler, who grew up in Leipzig.

"My father and mother and I would all share a single potato for breakfast. We were shocked to hear that our food supply was under threat."

Materna, too, recalls the importance of eliminating the beetles.

"We had just survived World War II. I had lived under all four occupying powers - we had been through a lot," he says.

"So if there were potato beetles, we needed to get rid of them, so we had enough potatoes. It was as simple as that."

The idea of planes dropping potato beetles over enemy fields was not entirely far-fetched.

For one thing, US planes were often flying low over some parts of East Germany at the time - delivering supplies to West Berlin.

And, says Erhard Geissler, several governments had already considered the possibilities of the potato beetle as a weapon - although he has found no evidence that they were ever actually used in practice.

The British considered dropping them over Germany during World War I, for example. And although Hitler had prohibited active research into biological weapons, a small group of German scientists performed a number of tests dropping specially-bred potato beetles out of planes in 1943. The idea was soon abandoned.

In East Germany in 1950, the Ministry of Agriculture commissioned a report to back up its allegations that the Americans were dropping beetles out of aircraft, including interviews with eyewitnesses and experts.

But the "experts" quoted in the research had never published previously on potato beetles or any other invasive species, Geissler says, and the committee was mainly made up of politicians, not scientists.

And so, he concludes, the story was aimed at covering the government's own inability to fight the beetles, and provided a handy extra accusation to hurl at the Americans.

He believes that the East German government did not believe the story themselves. "They were not stupid. They had political convictions and they were concerned by the increasing danger of the developing Cold War, but I do not think they were stupid enough to believe their own propaganda.

"There is no factual basis for the story about the Yankee beetles at all."

Lucy Burns was reporting for Witness - which airs weekdays on BBC World Service radio. You can hear her report on the potato beetles here.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external