Gong Haiyan: China's number one matchmaker

- Published

China has always had matchmakers but none quite like Gong Haiyan, who set up the country's largest online dating website as a graduate student, 10 years ago. It now has nearly 100 million users.

As we are packing up our camera equipment, Gong Haiyan hitches up her skirt and shows me a long purple scar on her right leg.

"A tractor accident," she says in her matter-of-fact voice. "In the school holidays I was trying to earn extra cash by selling ice creams. But on the way to the factory the tractor fell into a ditch and I was crushed underneath."

Gong, one of China's leading female entrepreneurs, started young. The self-made millionaire was born in a village in Hunan Province where everyday life was a struggle.

Her grandfather, once a wealthy landowner, was persecuted in the Cultural Revolution. As a result, his son was not allowed to finish primary school. But although her parents had received little formal education, they were fiercely ambitious for their daughter.

After the accident, Gong went to high school and like hundreds of millions of rural Chinese migrated to the coastal region where she worked in a TV factory. She wanted to help pay for the medical bills which had nearly crippled her family.

But she soon got bored on the assembly line and went back to her studies. Then she won a place at Peking University where she was ranked the top scholar from her province before moving to Fudan University in Shanghai for her Masters.

Gong's shares in Jiayuan are worth $45m

Her love-life, however, was non-existent and her parents began to worry.

"I was more than 25 years old and by Chinese standards I was a leftover woman," she says. "My mum and dad kept nagging me to get married."

So Gong paid 500 RMB (just over £50 or $80) to register with a dating website. But she got no replies and later discovered the company had stolen lonely-hearts profiles from other websites.

"I wanted to get my money back," she says. "But I was refused a refund and those people just laughed in my face."

Gong was bluntly informed that she was "not particularly beautiful or charming" and that "successful men couldn't possibly be interested" in her.

"I felt very angry," she says, "so I asked a friend of mine how much it costs to make a website and I set up my own dating service."

Like Facebook, Gong's website was set up from her college dorm and the first person to post a profile was her best friend, a fellow student. Four days later she persuaded the second person to sign up.

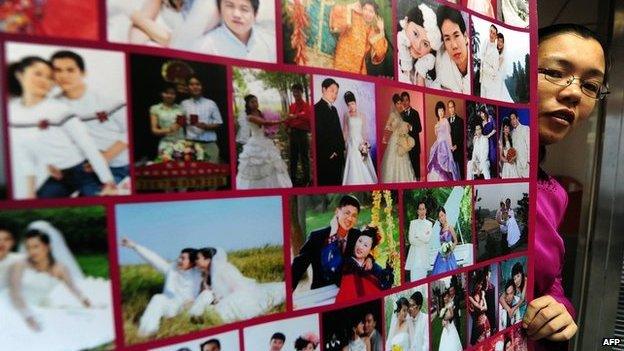

Ten years on Jiayuan.com, which means beautiful destiny, has nearly 100 million users and offices in several Chinese cities.

In the reception of the Beijing head office there's a flickering screen under a pink heart with two sets of numbers, which keep climbing relentlessly.

On one side there are the new registrations and it seems that several people sign up every few seconds. On the other side there are the successes - including those who now describe themselves as in a steady relationship with people they've met on the site, and those who are now married.

There are no figures for divorces and break-ups but I'm told that the company is valued for its serious approach to relationships. "Our users are looking for life partners, not a bit of fun," says Gong.

In May 2011, she travelled in triumph to New York where her company had its initial public offering on the Nasdaq and became the first Chinese dating site listed abroad.

But arguably Gong's most important victory was when she found her husband-to-be on the website.

Wei Tian Guang lives in Tanjen, Guangxi province, where in his class at school there were 20 boys and only six girls

When Gong's parents got married, there were three standard gifts from the groom's family, often nicknamed the "three rounds" - a watch, a bicycle and a sewing machine. Later brides expected a TV, washing machine and refrigerator. Now, a car, a flat and a good salary are the new holy trio for matrimony.

But Gong says she didn't care about material wealth. "I was looking for somebody smart, kind-hearted and healthy."

Guo Jian Zeng, a scientist who studies fruit flies, passed the first hurdle with flying colours.

"I made him take an IQ test," says Gong. "And he scored five points higher than me."

She adds that she was also impressed by his warmth and readiness to help others, from close relatives to strangers on the street. His profile picture also caught her eye.

"He was wearing a T-shirt and I could see that he had lots of muscles. He even won an iron man championship at his health club," says Gong, poker-faced.

The couple met six months after the launch of the website, in 2003, and were married three months later. They now have a four-year-old daughter.

China's Number 1 Matchmaker, as Gong is known, is following an ancient tradition. The art of pairing people off has a 2,000-year history going back to the Zhou dynasty.

Every village used to have its Red Mother, a local woman employed by families to find the right partner for their sons and daughters. Later local party officials and factory bosses sometimes played a similar role.

But now, says Gong, with rapid urbanisation, the old methods don't work any more.

"For migrants from the countryside like me, it is next to impossible to rely on the old social networks to find a husband," she says.

"When I got to Shanghai I had no friends or family there."

She adds that China's economic rise has also led to higher expectations and bigger disappointments.

"There is an information asymmetry - the person you are looking for does exist but you don't know where to find them," she says.

"On the other hand, because you are aiming for such an ideal partner, the person who does have the qualities you are looking for might not love you back in reality."

The marriage market is especially tough for men these days. Since the strict implementation of family planning policies in the 1980s, the male sex ratio at birth has continuously climbed.

Thanks to a traditional preference for sons, China now has one of the world's most dramatic gender imbalances with 118 boys born for every 100 girls.

According to official statistics, by the end of this decade there will be 24 million "leftover men" of marriageable age. Between 2020 and 2050, some scholars estimate that 15% of Chinese men will not find a wife.

"In my home town in Hunan province we can already see this problem," says Gong.

"A lot of men who are 40 or 50 years old have been single all their lives and have given up hope of finding anyone to marry.

"I feel that in the future if more than 20 million men cannot find a wife this could bring serious social problems. We hear on the news about more single men visiting prostitutes for example. Everyone needs a mate - a life partner - this is a very basic need for every human being."