Jesse Jackson and the US airman shot down by Syria

- Published

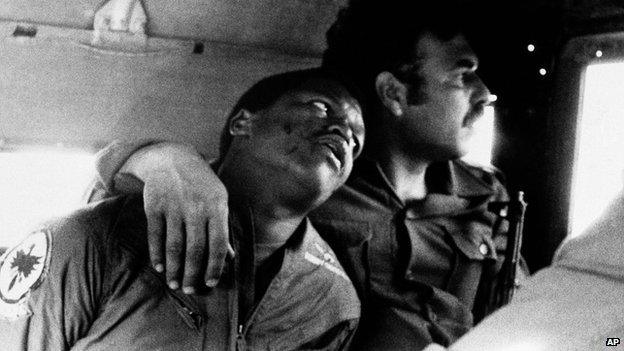

A week before his release, Goodman (left) was photographed in the back of a car with a Syrian soldier

Earlier this year, the US was on the verge of launching air strikes against Syria, which would have meant US air crew becoming targets for Syrian anti-aircraft fire - just as they were 30 years ago when Lt Robert O Goodman was shot down over Lebanon.

"I remember thinking very clearly - I have been cast into a position in the middle of this conflict in the Middle East, which has been going on for hundreds, if not thousands of years, and which I've been trying to solve with thousands of pounds of bombs," Goodman recalls today.

Lebanon was in the throes of a brutal sectarian war. Myriad Lebanese factions were fighting one another, but also large numbers of Syrians and Israelis.

US forces were part of a large multinational force that had arrived to help broker peace - but as time went on they were getting sucked into an open confrontation with Damascus.

Goodman, a 27-year-old navigator, and pilot Lt Mark Lange, took off in an A6-E Intruder on 4 December 1983 from the aircraft carrier, USS John F Kennedy, positioned off the Lebanese coast.

Their mission was to drop 1,000lb bombs on Syrian tanks and anti-aircraft in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, close to the Syrian border.

With incoming missile and small arms fire from the Syrian forces on the ground, Goodman remembers feeling his aircraft jolt forward and begin tumbling down. Both he and Lange managed to eject and parachute to the ground as the burning plane fell to earth.

The next thing Goodman remembers is being tied up and tossed in the back of a truck. He had no idea where he was being taken - or indeed who his captors were. And it was only later that he learnt that had Lange died of his injuries.

"Once we got to Damascus I was taken to a cell and then brought up for interrogation," he says. That was when he saw a portrait of the Syrian president, Hafez Al-Assad, on the wall.

Strangely, it filled him with relief. It was better to be held by the Syrians than one of the militias fighting in Lebanon.

The Syrians were anxious to know about his bombing mission, what his plane was carrying, what his target had been. Goodman was equally anxious not to tell them any details - or let on that he had been shot down before a single bomb had been dropped.

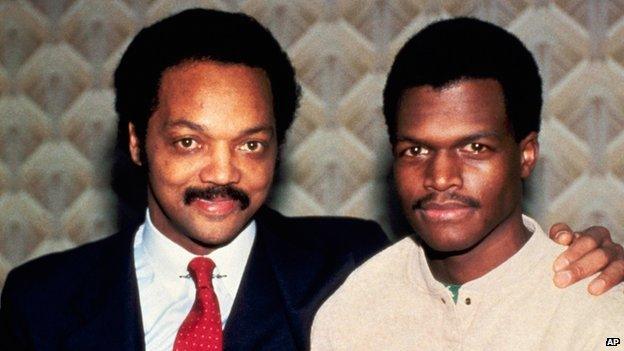

Goodman, right, with his family, soon after his release

"They weren't aggressive, they didn't threaten me, they were just persistent," he recalls. "It was stressful because I was trying to make stuff up, and also remember what I was making up in case they asked me about it again." Between interrogation sessions, he was left alone in his basement cell, with only a single light bulb and little sense of time.

"It felt rather foolish," he says. "And I'm thinking, I am here in this cell, and they can do anything they want with me, and no-one will ever know."

He feared that no-one outside of those four walls knew what had happened to him.

But after four days in captivity, he was visited by a member of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who brought him news from the outside world - and messages of support from his family. "That was incredibly encouraging," he admits.

In fact, news of his capture had spread quickly around the globe. From across America, people sent Christmas cards to the US State Department for him. His mother made a public appeal for his release. He was visited in captivity by the US ambassador to Syria, Robert Paganelli, and a delegation of religious leaders led by the black civil rights leader, the Rev Jesse Jackson, travelled to Damascus to petition President Assad for his release.

"Assad's argument was that Lt Goodman was not a tourist, he was a soldier and he shouldn't have been there," Rev Jackson told the BBC in a recent interview. "My argument was that it was a mistake and that he wasn't on a bombing mission in Syria, and that letting him go would be a sign of good will."

Christmas 1983 came and went, with little sign of a release. Jackson's delegation had met several top Syrian officials, but had not succeeded in securing a face-to-face meeting with President Assad himself. Meanwhile, Goodman was moved to a bedroom on the second floor of another building, where his guards, young conscript soldiers, seemed more interested in practising their English than interrogating him.

"They would come in and strike up conversations, ask how old I was, whether I was married - all sorts of generic questions that I found quite unnerving," Goodman recalls.

On the television in any adjoining room, he could see footage of angry demonstrators in Damascus burning effigies of President Ronald Reagan. Goodman was constantly worried that a mob out on the streets might try and break in to seize him.

Then, on 2 January 1984, the US delegation was summoned to see the Syrian leader.

"He was serious, as we were, not strident, but still resolved to keep him (Goodman)," Jackson recalls.

He told President Assad that their two countries were not at war and that the young airman was not a prisoner of war. And he suggested that releasing him would open the possibility of a channel of communications with Washington.

Then early the next morning, without explanation, one of the guards woke Goodman and told him to collect his things. He was taken outside, put in a car, and driven to a Damascus hotel where Jackson and his delegation were waiting.

Throughout his four weeks in captivity the young airman had been careful to remain "on an even keel, not to get too excited or too depressed".

But now he knew his luck had changed. As he sat in the back of the US military plane taking him home, everyone else around him was celebrating his release.

Assad had decided to release Goodman, Jackson says, because it was in his interests to do so.

"It was a joyous moment," he recalls.

Goodman says what he felt most was "incredibly tired".

Two days later both men stepped off the plane back in Washington. Goodman was reunited with his family, and then was whisked off to be met by a beaming President Reagan at the White House. He was feted as an American hero - a role, he says, he still does not feel comfortable with.

"That's something I have never been able to reconcile. I didn't feel I had done something heroic. I look back on it as an interesting slice of time, but not something I conquered - rather as something I managed to get through."

Jesse Jackson and Robert O Goodman spoke to Witness - which airs weekdays on BBC World Service radio. You can hear Mike Lanchin's report here.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external