Viewpoint: Have drug scandals actually made sport more interesting?

- Published

- comments

Usually drugs in sport are the subject of universal condemnation, but have they actually made things more interesting, asks Paul Dimeo.

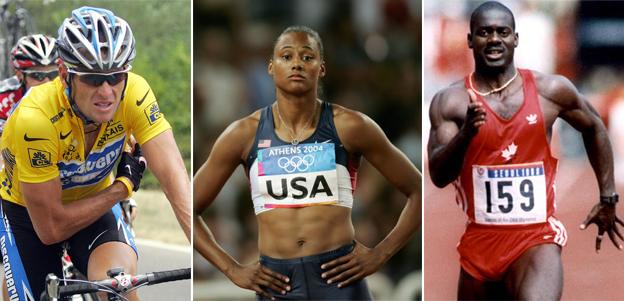

I was 17 when Ben Johnson became a household name. Not for winning the 100m gold in the 1988 Olympics, but for losing that medal two days later after a positive test for the steroid stanozolol.

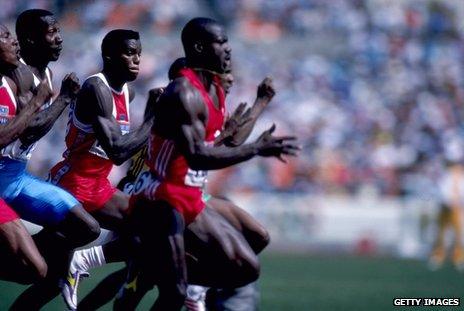

Twenty-five years after Johnson's ignominy, he is now promoting an anti-drugs message, while I teach and study sports policy, and in particular drugs in sport. I've watched the Johnson race hundreds of time, telling my students to watch Carl Lewis's face drop in amazement at Johnson's speed.

It is now one of the most famous events in sports history - famous for Johnson's positive and for the fact that many of the other runners were implicated in doping at some stage of their career.

Carl Lewis glances at Ben Johnson speeding ahead in the 100m final

I've also become fascinated by professional cycling, a sport of which I knew nothing about until 10 years ago when the story of the Lance Armstrong miracle was increasingly circulating - the great hero who recovered from cancer to dominate the sport.

As a lecturer in sports I often come across people who are wholly devoted to the ethical purpose of sport, to the idea that sport can help improve lives. I also meet people whose approach to sport is about performance - sports scientists, coaching experts and others who are helping to develop training techniques, nutritional strategies or technologies that can support what my Danish friend and colleague Verner Moller calls the will to win.

Over the 25 years since Johnson's eye-popping, steroid-fuelled brilliance was savagely cut short and his life ruined, I have increasingly found myself fascinated by the moral ambiguities produced by the tensions between these competing paradigms. And I have come to see the ongoing war between the dopers and the anti-doping policing agencies as a manifestation of these historical dilemmas.

After a doping scandal, we are encouraged to take the side of traditional ethics and support anti-doping. However, if we can empathise with athletes' will to win and desire for competitive advantage, which as spectators we celebrate and admire, we might be less harsh in our judgement.

Ben Johnson and Lance Armstrong both thought others were doping - and they were right. They both felt they could not trust the anti-doping system to protect the idea of fairness - and they were right about that, too. Their doping was driven by the belief that they were only doing what they had to do to win. Yet they have both been punished very severely while others have got away with it. I can't help but have some sympathy.

And when you start looking at the question from that angle, another thought presents itself. What if doping has done something good for sport? What if, in fact, doping has helped make sport what it is today?

The best example is the Olympics, which was in crisis for most of the post-war period. Essentially it is a series of minority interest sports brought together with reference to the historical idealism of international peace and co-operation. In theory it was entirely amateur and the big professional sports like football, cycling, tennis, golf and American football were not represented. In the words of Jim Mills Sr, it was little more than PE for grown-ups.

Few countries wanted to host the event , there was little sponsorship money and, beset by boycotts, the movement nearly collapsed. However, what made the Olympics interesting through the 1960s, 70s and 80s - breathed life into the whole affair - was the Cold War rivalry between the Soviet Union, East Germany and the US and their respective allies.

This rivalry created meaning and a culture of excellence. Records were regularly broken in almost all disciplines. Great performances were admired while ongoing rivalries - individual and national - made for great stories. But we know now that many of the Olympic medal winners from those countries in these decades were on steroids. The growing popularity and media coverage of the Olympics was based upon excellence fuelled by steroids.

The writer Umberto Eco once argued that sport isn't really about the actual event - that's over quickly, few people participate and only a relatively small number will be there to see it in real life. Instead, Eco wrote, sport is about reporting an event, then discussing the reporting of the event, then discussing the discussion. And drugs have certainly enhanced the discussion as much as they have enhanced the athletes. The discussion around sport - from newspaper headlines to in-depth biographies - has benefited greatly from drugs. The public love stories where drugs make sports stars seem like human beings - tragically flawed.

But it goes beyond that. Anti-doping is a moral and controlling force which aims to protect the purity of sport, but like all moral forces runs up against human nature - in this case athletes' will to win, and their occasional lapses in concentration.

Anti-doping would not exist without doping as its nemesis - the two are locked together, they need each other. It is a war in which each side defines the parameters of the other. And this has created a real sense of fascination among sports fans, and even those not normally interested in sport.

Danish cyclist Michael Rasmussen admitted to using EPO and other drugs

Personally, I have made a career from discussing doping - writing and teaching about Cold War rivalries, doping at the Olympics and the wider history of drugs in sport. People talk to me almost every day about it. One of my students asks for my thoughts on the latest scandals and new policies. My weekend cycling buddies ask me what they are allowed to take to enhance their chances of success. Even a friend who is a former church minister once asked me why people are so angry with Lance Armstrong. After all, she said, in the bigger scheme of things he hasn't done much wrong.

Most of all though I get to indulge my curiosity about sport, which is also about life, to explore that liminal space between what is judged to be right and what is wrong. My critical anti-authoritarian streak relishes instances where supposedly bad turn out to be good, and the supposedly good turn out to be bad.

When I look back at Ben Johnson and at others - Marion Jones, Michael Rasmussen, David Millar, Marita Koch and so many more - I see people driven by a desire to win, for themselves and their families, and I can't bring myself to see anything wrong in that.

This is an edited version of Paul Dimeo's Four Thought, which will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 20:45 BST on 9 October 2013.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external