A Point of View: The man who dreamed of the atom bomb

- Published

Leo Szilard was the man who first realised that nuclear power could be used to build a bomb of terrifying proportions. Lisa Jardine considers what his story has to say about the responsibilities of science.

The figure of Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard loomed large in our house when I was a child. He was held up to me as an exemplary figure in science - a man who had made fundamental breakthroughs in nuclear physics, but whose acute sense of moral probity led him in the end to denounce the very advances he had helped make. Only later did I learn an alternative version of his story.

Almost exactly 80 years ago, in early October 1933, Szilard was in London, in transit from Nazi Germany, when an idea came to him that would lead directly to the ultimate weapon of war - the atomic bomb.

An article in the Times two weeks earlier had reported a lecture at the British Association by Lord Rutherford - the Nobel Prize-winning New Zealand physicist and head of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. Rutherford had described splitting the atom by bombarding it with protons, but had gone on to say that any suggestion that the energy released might be harnessed as a source of power was "talking moonshine".

The report caught Szilard's attention. He pondered it obsessively. Surely Rutherford was wrong? Then, early on a dismal, grey morning, as he waited on foot at a traffic light to cross busy Southampton Row near his hotel, the answer came to him in a flash.

If a neutron, fired at an atom, produces the release of, say, two neutrons, each of which hits another atom, which both in turn release two more neutrons, which each go on to collide with two further atoms, a nuclear chain reaction would take place, releasing unimaginable amounts of energy.

Szilard tells this story twice, with slightly differing details. But the tale itself is consistent and delightfully vivid. The challenge of Rutherford's remark, the heavy cold that had prevented Szilard's attending the lecture, the days spent thinking about it and the flash of inspiration just as the traffic light changed.

Szilard immediately recognised the importance of his idea. To ensure its security he patented it in the name of the British Admiralty. The patent included a clear description of "neutron induced chain reactions to create explosions".

In August 1939, by which time Szilard had moved on to the US, he wrote to President Franklin Roosevelt to inform him that "a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium" was undoubtedly possible, and could lead to the construction of "extremely powerful bombs of a new type". Germany, he warned, might even now be developing such a weapon. "A single bomb of this type," he wrote, "carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory."

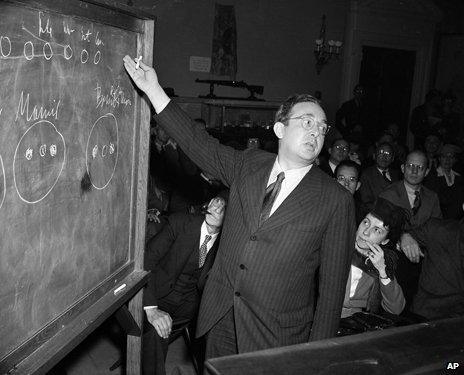

Leo Szilard in 1945

The letter was signed by Szilard and Albert Einstein. By the time it reached Roosevelt, Germany had invaded Poland. With war now a certainty, the urgency was not lost on the US president. A committee was set up to pursue the nuclear initiative, out of which emerged what came to be known as the Manhattan Project - the hugely ambitious and massively funded programme to develop a functioning atomic bomb in the shortest possible time.

But less than six years later in 1945, Szilard campaigned with equal passion to persuade the American government not to use the atomic bomb against a civilian population. He understood better than anyone the enormity of the devastation such a weapon could cause. But his petition, although signed by a large number of nuclear physicists, never reached the president.

So devastated was Szilard at his failure to avert the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the story I was brought up on concluded) that he refused to do any further work in nuclear physics. Instead he moved research areas entirely, to molecular biology - a field concerned with the origins of life rather than its destruction. To my father this audacious step captured the essence of scientific moral responsibility. And I carried Szilard's story with me as I grew up.

Today, however, I know that inspiring as it is, there are problems with this tale. As often happens with history, we have to treat with caution a narrative that fits so neatly the interests and preoccupations of the age in which it is written.

At the time I was being told this story, Britain was in the depths of the Cold War. In the post-war years it turned out that Szilard (and indeed my own father) found it impossible to obtain work on any scientific project that involved nuclear physics. Though they were barely aware of the stigma themselves, the communist sympathies of their youth barred them from getting the necessary security clearance.

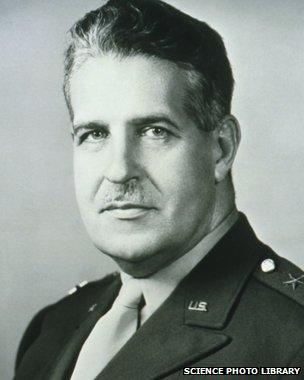

Szilard's wartime boss Gen Leslie Groves suspected him of Russian sympathies

So Szilard did not leave physics of his own accord. At the end of the war he was abruptly dismissed from the Manhattan Project by its military head, Gen Leslie Groves. Groves had always suspected him of having Russian sympathies, and now deemed him too high a security risk. Forced to change field, Szilard was indeed prescient in choosing molecular biology, which less than a decade later would uncover "the secret of life" in the form of the structure of DNA.

My father's exemplary tale unravels further when we consider the way it presents the progress towards a functioning atomic bomb. It narrates a smooth development from Rutherford's lecture in London, through Szilard's (and his fellow emigres') journey from Nazi Germany via London to the US, and Szilard's single-minded preoccupation with the potential threat of nuclear weapons, to the Manhattan Project, and finally to its very American triumphant - or tragic - outcome.

But actually Szilard the Hungarian had carried out the crucial early research with the Italian emigre Enrico Fermi, continuing it with him in the early years of the Manhattan Project, where the two of them succeeded in creating a controlled chain reaction - a prerequisite for a functioning bomb. Meanwhile, independently in Britain considerable progress was being made towards a nuclear weapon (a project code-named "Tube Alloys") with the direct encouragement of the prime minister Winston Churchill (who as Graham Farmelo tells us in a recent book, was surprisingly up-to-date himself in nuclear physics). In September 1940 the so-called Tizard mission delivered the top secret work of Tube Alloys to the Americans, to be developed with the greater manpower and financial resources available in the US. The British work made its own vital contribution to the project.

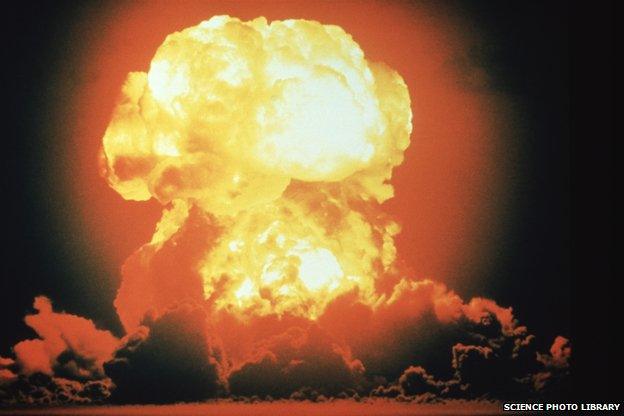

Trinity monument in US state of New Mexico - site of the first atomic bomb test

Here is a much more fragmented, syncopated and international story, in which it is entirely unclear whether any one nation ultimately takes the credit or blame for the science and engineering behind the atomic bomb. Nor does it carry the clear didactic message of my original.

There is one final twist to what started out as a simple story. Some of you will have noticed that I gave the date of Szilard's eureka moment at that traffic light on Southampton Row as October 1933. You may have had a date in September in your mind. The truth is, Szilard tells the story twice, as I mentioned. In one version he records reading the Times report and immediately having the idea of a chain reaction (on 12 September). In the other he recalls fretting over the problem for weeks in his hotel room and pacing the streets of London deep in thought, until the idea eventually came to him (in early October).

So although the beginning of the story comes from the mouth of the man himself, we cannot be certain which version is correct. As a historian I have chosen the second as the more plausible, particularly in view of that heavy cold which Szilard tells us prevented his attending Rutherford's lecture on 11 September. But that remains surmise.

Historical narratives are never without their agendas. My father's generation lived under the shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki - he had been sent to do reconnaissance there only a few months after the bombs were dropped and had seen the consequences all too close up. He told me a story which redeemed the scientist from the enormity of events brought about by fundamental research in physics. It was a story that held the scientist responsible for lethal applications of "pure" research, and proposed Szilard as an iconic figure, for recognising and taking that responsibility upon himself.

My father's story of Leo Szilard may not have been the truth. But it taught me, as a child, a lasting, salutary lesson about science and human values.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external