The drugs derived from deadly poisons

- Published

These days we have access to a huge array of medicines to protect us from pain, disease and death. But, as Michael Mosley has been discovering, the source of many of our more remarkable medicines have been deadly poisons.

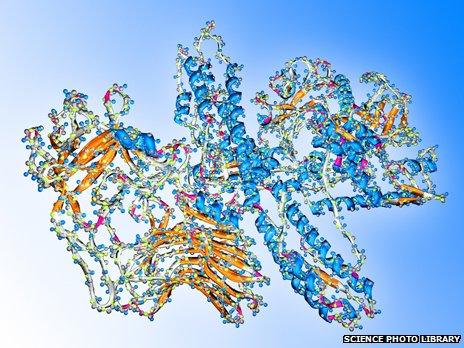

Take a look at this picture.

It is the most poisonous substance known to man. A couple of teaspoons would be enough to kill everyone in the UK. A couple of kilos would kill every human on earth. It is so dangerous that it is manufactured in military installations and at around £100 trillion per kilo it is also the most expensive substance ever made. Yet despite being so toxic and so costly it is in huge demand. Many people pay large amounts of money to have it injected into their foreheads.

It is botulinum toxin - better known as Botox - a toxin produced by bacteria first discovered in poorly prepared sausages during the 18th Century. It was named after the Latin for sausage - botulus.

On the LD50 toxicity scale, which measures how much of a substance you would need to kill half the people it is given to, Botox measures just 0.000001 mg/kg. In other words you need would need around 0.00007mg to kill a 70kg man like me. Or to put it another way, a lethal dose for me would weigh less than one cubic millimetre of air.

Botulinum toxin kills its victims by causing respiratory failure. It is a neurotoxin - it enters nerves and destroys vital proteins. This stops communication between nerves and muscles. Only the growth of new nerve endings can restore muscle function, and that can take months.

Its main claim to fame is that it will iron out wrinkles in ageing faces and does so by destroying the nerves that cause frowning. The quantities used are tiny - a few billionths of a gram, dissolved in saline. In the name of science I tried Botox a few years ago.

It certainly smoothed away the wrinkles but it also gave me a weird expression, until the new nerve endings grew.

But botulinum toxin is far more than simply a vanity product. It is extremely useful for treating a number of medical conditions, ranging from eye squints to migraines, excess sweating to leaky bladders. In fact there are currently more than 20 different medical conditions that botulinum toxin is being used to treat. More are being discovered all the time.

A Botox facelift

Botulinum toxin is just one example of extraordinarily dangerous poisons that have useful medical applications. Captopril, a $1bn antihypertensive drug, was developed from studies made on snake venoms. Exenatide, marketed as Byetta, is an effective and extremely lucrative drug used to treat type-2 diabetics. It comes from studies of the saliva of the Gila monster, a large venomous lizard that lives in the south-western US and Mexico

But the impact of poisons on modern medicine go deeper than simply providing new forms of treatment. One poison in particular helped shape the entire modern pharmaceutical industry.

In Victorian Britain, life insurance was a booming industry. This easy money led to a surge in murders, many of them by poison.

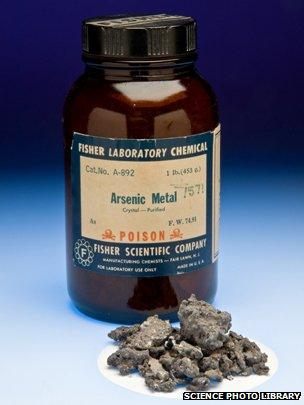

Oxides of arsenic are tasteless, soluble and very deadly

One of the most high profile cases was a woman called Mary Ann Cotton who, in 1873, was tried for multiple murders. She had been married four times and three of her husbands, all heavily insured, died. The one who survived seems to have done so because he refused to take out insurance. So she left him.

In all, 10 of her children died of what seemed to be gastric-related illnesses. Each must have been a tragic loss, but fortunately for Cotton most were insured.

Her mother, her sister-in-law, and her lover all died. And in each case, she benefited. By 1872, the unfortunate woman had lost an astonishing 16 close friends or family members. But there was one left - her seven-year-old stepson, Charles. She tried to give him away to the local workhouse but they wouldn't have him. So young Charles soon died.

The manager of the workhouse, however, got suspicious and contacted the police. They soon decided Cotton must have poisoned the boy and thought they knew how she'd done it - with arsenic.

Arsenic oxides are minerals and as a poison are almost unrivalled. They are tasteless, dissolve in hot water and take less than a hundredth of an ounce to kill. Yet in the 19th Century, marketed as a rat poison, arsenic oxide was cheap and easily available. Children would blithely collect it from the shops along with the tea, sugar and dried fruits.

The trial of Mary Ann Cotton would hinge on whether they could find traces of arsenic in the body of her stepson. Forensic science was still in its infancy but they did have a good test for arsenic. This was because there was an awful lot of arsenic poisoning around.

A sample from the boy's stomach and intestines was heated with acid and copper. If arsenic was present, the copper would turn dark grey and, when placed on paper soaked in mercury bromide, produce a tell-tale yellowy-brown stain.

When they tested the body of poor little Charles they discovered that he had indeed died of a lethal dose of arsenic. Cotton was convicted of his murder and hanged in Durham Jail. She was never taken to trial for the mysterious deaths of her mother, three husbands, two friends and 10 other children.

It was a rash of murders and poisonings like this one that led first to the Arsenic Act and then to the Pharmacy Act 1868. This act ruled that the only people who could sell poisons and dangerous drugs were qualified pharmacists and druggists.

So it was from poisonings, accidents and murders that the modern legitimate business of pharmacy finally emerged. And one compound - arsenic trioxide - has also found a legitimate medical use, as an anti-cancer agent.

Pus, Pain and Poison is on BBC Four, Thursday 17 October at 21:00 BST and you can catch up oniPlayer.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external