Can you persuade people not to buy stolen goods?

- Published

What's the best way to dissuade people from buying stolen goods? Past experience suggests there's a way to make it socially beyond the pale.

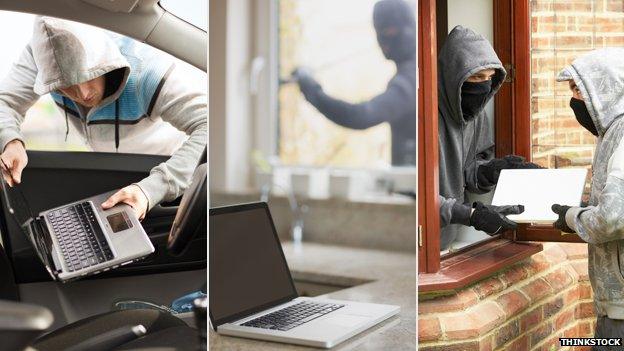

A man comes up to you in the pub. "Nudge, nudge," he says, conspiratorially. "Can I interest you in a brand new laptop. Perfect nick. £100. Say no more."

Of course, you assume that the shiny machine is almost certainly stolen. So what does one do?

You know the correct answer is to say you'd make a citizen's arrest while the landlord telephones the local constable. But the black market in stuff that just might have fallen off the back of a lorry predates lorries and probably the invention of the wheel.

For many people, getting a bargain trumps the technicalities of Section 22 of the Theft Act 1968, external. Especially if they think the risks of being caught are about zero.

But without a market in stolen goods, there would be no property crime and the misery that goes with it. As Patrick Colquhoun wrote in 1796 in A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis, external, "deprive a thief of a safe and ready market for his goods, and he is undone".

I mention all this because of a submission that has been sent to the Justice Select Committee. It suggests that, when it comes to the black market, "nudge, nudge, say no more" is not the problem but the possible solution. Allow me to explain.

In 1979, 28 people a day were killed or seriously injured by drunk drivers. Thirty years later and the number had been reduced to four. What had changed?

The Department of Transport asked the same question last year when it produced a short research paper, external. The analysis concluded that the fall in drink driving wasn't just down to tougher punishments and greater enforcement. It was down to a brilliant bit of nudging.

The nudge in this case was an advertising campaign between 1987 and 1992 that, in the words of the transport minister at the time, was about "changing the water in which the fish swim". The campaign set out to produce a sea-change in the social acceptability of drink driving. The brief was to create nothing less than disgust at those who drank and then drove.

You may remember the ads:

the fireman breaking down after seeing a crash scene involving a mother and a baby

schoolchildren's heart-breaking reaction to the death of a classmate

a girl crying while her mother rails at her father for killing a little boy

Before the campaign 51% of men agreed "it is difficult to avoid some drinking and driving if having any social life". Afterwards the figure fell to 30%.

The advertising messages had helped change the norm. The shift in attitudes seemed contagious. Drink driving was not just a crime - it had become socially unacceptable, and it was unacceptability rather than criminality that was the major reason why people did less of it.

A Department for Transport billboard in 1987

Let us now return to the submission that's been sent to the Justice Select Committee. It comes from the security company It's Mine Technology, and claims to take an evidence-based approach to crime prevention - combining "effective technologies with behavioural science".

The company doesn't mince its words. "There is little empirical evidence that anything the Ministry of Justice has ever done since its inception in 2007 has had any impact on the commission of crime."

The submission goes on to claim, external "the police have no idea what effective role they have had in reducing crime, no idea, based on evidence, about what works and little or no evidence to back any initiatives".

"Ignorance of, and lack of respect for evidence and the scientific method bedevils the whole area of crime policy," the authors assert.

The document makes the point that much of the thinking underpinning crime policy development is based on "expected utility theory" - broadly the idea that potential criminals make rational decisions on whether to commit a crime based on risk and reward.

The evidence from behavioural economics, it is argued, suggests the opposite. Decisions on whether to commit a crime are usually irrational and bear little relationship to any risk v reward calculation. In fact, thieves overwhelmingly do not even know the potential punishment for their crime.

The key to reducing crime, the submission suggests, is nudging - encouraging people to behave in pro-social ways without conscious thought.

When it comes to the black market in stolen goods, might it be possible to make such trades as disgusting as drink driving? The submission document believes we should try.

"Behavioural change can be contagious," it argues.

"There is good evidence that everything from smoking to obesity, happiness, loneliness, co-operation and generosity can be 'caught'."

So if buying a dodgy laptop or some smuggled cigarettes were to be regarded as socially beyond the pale, then the black market would crumble.

How the Nudge Unit tries to get people to change their behaviour

Rather than thinking they'd happily stumbled across a bargain, drinkers in the snug would recoil.

The authors of the submission suggest, as a first step, the default position should be that anyone found in possession of stolen goods be prosecuted under the Theft Act.

One could imagine a hard-hitting advertising campaign, running alongside the tough legal stance, pointing out the distress that lies behind every item of loot offered in the pub.

Perhaps the strapline might be: Nudge, nudge, say "no more".

- Published18 October 2011