Are children given too many toys?

- Published

Retailers are starting to gear up to sell the latest generation of Christmas toys, but some campaigners are advocating a change in attitude. Do some Western children have too many toys, asks Joanne Furniss.

I stood in the playroom holding an empty suitcase. We were emigrating and could only pack a few toys to keep us going until the rest arrived by ship months later.

In went the Story Cubes - ingenious picture dice that inspire stories, drawings or full-scale theatrical productions. Both kids are "crafty", so in go pom-poms, pipe cleaners and paper punches. Next, a kingdom of animal figurines marches two-by-two into the case.

I subject the rest to an eligibility test before I transport them half way round the world from Switzerland to Singapore - has either child shown the slightest interest in the toy in the past month?

An ancient game of Pass the Pigs passes muster. A bucket of unisex Duplo and then, after a tantrum, a second bucket of pink Duplo. At the last minute, I spot a "snakes and ladders" game that my son enjoys (provided he gets to take all the turns).

A selection of toys in Joanne Furniss's home

But the rest has not been touched in a month - and the shelves are still packed with dolls and jigsaws and trains and kazoos and knitted muffins and the emergency vehicles of several nations and enough wooden blocks to build a bridge to Singapore.

So why do we have so many toys?

Psychologist Oliver James, author of the parenting book Love Bombing, believes children don't "need" a vast panoply of toys.

"Most children need a transition object," said James, "their first teddy bear that they take everywhere. But everything else is a socially generated want."

It seems we are keen to generate our children's wants - the Toy Retailers Association reports that the British alone spend £3bn each year on toys.

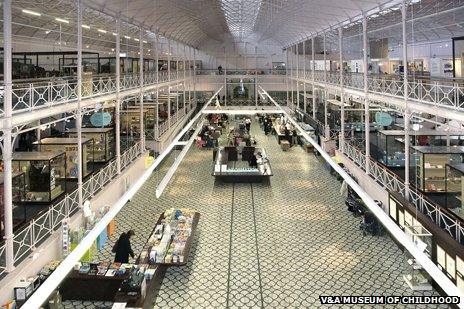

The V&A Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green, London

At London's V&A Museum of Childhood, Catherine Howell oversees a collection that includes a 400-year-old rocking horse and Buzz Lightyear. She agrees that children typically have far more toys than any previous generation.

But while spin-off merchandising has been a huge hit ever since Star Wars figures appeared in the 1970s, Howell says traditional toys like dolls and building blocks have retained a consistent popularity. "A child always comes back to a set of bricks because it allows them to use their imagination."

Certainly, my own three-year-old is a marketer's dream, desperate to adventure with the Octonauts (an animated series). And yet, when his much-anticipated Gup-B arrived last Christmas, his underwater enthusiasm had ebbed by Boxing Day.

According to James, toys that pre-determine play - and this is especially true of merchandising - offer limited possibilities for fun. So while Buzz Lightyear can only ever be a space ranger, a doll might become a hungry baby, a tea party guest - or a space ranger - depending on the child's desires.

These prescriptive toys could even be damaging, says James. "Young children discover their identity through fantasy play. If their toys offer a limited repertoire, this process is eroded."

It is the "play value" that is most important, says Liat Hughes Joshi, author of Raising Children: the Primary Years. "There are enormous benefits to toys - they bring joy, creativity and learning."

Joanne's son likes to play with sticks

She sees three factors that make a brilliant toy: "Social value - a dolls' house allows children to play together, versatility - Lego bricks can be made into anything, and durability - such as a wooden train track that the child will use for years."

But James says it's even better for children to "colonise objects". A quick glance into the bedroom shows me that my two have recently colonised my baking trays (drums), towels and pegs (den) and a large plastic storage box (my son's ark, decorated with a portrait of God). It also explains their fascination with sticks, the Swiss Army knife of the imaginary world.

The sheer creative potential offered by found objects is a force that toymakers do try to harness. That old favourite, Meccano, recently won an award that recognises the traditional value of toys.

Thierry Bourret, the founder of the Slow Toy Awards, says there are many ways that well-designed products surpass "colonised objects", but one in particular is crucial. "How do you know an object is safe? Every toy we recognise has been safety tested and develops life skills."

Other 2013 Slow Toy winners included a stylish Danish-designed dolls pram, a set of ecological building blocks called TWIG, and a classic trike.

But how many toys is too many?

Those who advocate fewer toys say it is not just the nature but also the sheer number that threaten to overwhelm our children. And for parents who think that sibling rivals will bicker less if they have a wide choice of novelties - more toys could actually make them more selfish.

Joshua Becker, a father of two who writes about how to simplify both home and lifestyle, says: "People co-operate better and share when resources are limited, and the same is true for children."

This minimalism extends to the whole Becker family, with the kids given a confined space to store their toys, forcing them to adopt a "one in, one out" policy.

He sees his kids "filling their time with creativity" - taking their scooters to the park, practising baseball and football, inviting friends over to play with dolls, and devising art projects. In addition, he says, they develop longer attention spans, take better care of their possessions and grow more resourceful.

Crucially, Becker hopes these habits will last a lifetime. "The children realise they don't have to conform and be consumed by consumerism."

In his book Affluenza, James outlines how the populations of the UK and the US suffer a high degree of emotional distress related to the kind of materialism that Becker rejects. Meanwhile, residents of continental Europe are only half as likely to be plunged into misery by their frustrated desire for more stuff.

Is it a coincidence that the educational cultures of mainland Europe promote real-life learning experiences? The forest playgroup - or Waldspielgruppe - is a rite of passage in Switzerland, where I lived for seven years.

Starting at age three, my kids toddled off to nail their lumberjack skills with normal-sized hammers and saws. They built fires, cooked food and collected soggy pine cones. There was not a toy in sight. Just contented children - and a wealth of pine cone-themed ornaments.

Now that Swiss cold-snaps have been replaced by Singaporean monsoons, I'm grateful I didn't leave all the toys behind. Maybe the kids don't need them - but their busy parents do. The move forced us (willingly) to minimalise, and with all those empty packing boxes waiting to be colonised, we're not short of ways to play more with less.

What's the most imaginative toy your child has made out of an everyday object? Tweet your photo, external with #whatmychildmade.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external