Face, get back to work!

- Published

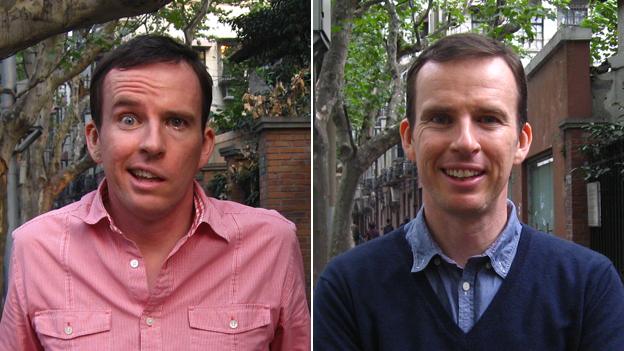

John Sudworth in November 2012, and today

One year on, the BBC's Shanghai correspondent John Sudworth reports on his slow recovery from Bell's palsy, and frowns, almost symmetrically, at the lack of medical awareness about the condition.

It may have taken a whole year, but the muscles on the left hand side of my face have been slowly drifting away from the picket line and getting themselves back to work. The strike, it seems, is over.

My left eyebrow, the left side of my mouth and my left eyelid have all reported for duty again and I can now do two of the most glorious and underrated things a human can do - smile and blink.

Shortly after the onset of my Bell's palsy, in October last year, I wrote about my decision to carry on working as a BBC TV reporter. The response was overwhelming, with many, many fellow sufferers writing to tell me about their experience coping with this facially disfiguring and deeply distressing condition.

So, exactly 12 months on, by way of returning some of that generosity, this is my own story of recovery from an illness that was recently shown to be more common than previously thought and one that deserves far more medical attention than it gets.

Watch how John's face recovered over the course of a year

Bell's palsy sufferers usually find themselves becoming overnight - and unwitting - members of a very strange club. There are no warning signs and most people simply wake to find that they can't move half of their face.

Although membership includes some pretty esteemed company, including the likes of George Clooney and Pierce Brosnan, it is not a club that anyone would choose to join. The paralysis can be shocking and, socially at least, very difficult to deal with.

The hardest part for me, as well as the loss of my smile, was the inability to close my left eye. Bell's Palsy leaves sufferers with one eye stuck permanently wide open, unable even to blink, sometimes for months on end.

Of course, the other, unaffected eye carries on as normal, merrily blinking away. So, for the record, my apologies to anyone who may have mistakenly thought I'd been winking at them for the past year or so. Except the barmaid in the Nag's Head. That was a wink.

The eye issue certainly presented a thorny dilemma in my TV reporting. With my left eye stuck open, the choice was to either force my right eye to do the same - in manic two-eyed stare - or to blissfully wink away at BBC viewers. Move over Anne Robinson.

Thankfully, as the above video shows, at some time between the six- and nine-month mark my left eyelid began to take instructions again.

Bell's palsy is thought to be caused by the waking up of a dormant virus, often at times of stress and lowered immunity, much in the same way as the chickenpox virus causes shingles long after the initial illness has passed.

The virus attacks one of the two facial nerves causing it to swell up and become constricted inside a bony passageway close to the ear. Signals then cease to be transmitted along it, paralysing one side of the face and rendering it expressionless.

The only treatment that has been shown to have significant, measurable benefit is a course of steroids, but it must be started early, within 72 hours of the onset. These steroids reduce the swelling and lower the risk of permanent damage to the facial nerve.

Remarkably, despite this clear evidence, a recent study, external has shown that many people (more than 40% in the UK) are still not getting the appropriate treatment. And the same study shows that Bell's palsy is more common than previously thought. The estimated incidence rate suggests that worldwide there are more than 7,000 new cases every day.

One year ago, as I was becoming acquainted with my own facial paralysis, Charles Nduka, a consultant plastic and reconstructive surgeon was setting up a new charity, Facial Palsy UK, which campaigns for better UK services for Bell's palsy and a range of related conditions.

"The information available online about Bell's palsy at the moment is pretty appalling," he tells me. "And there is very poor data because there is not enough research."

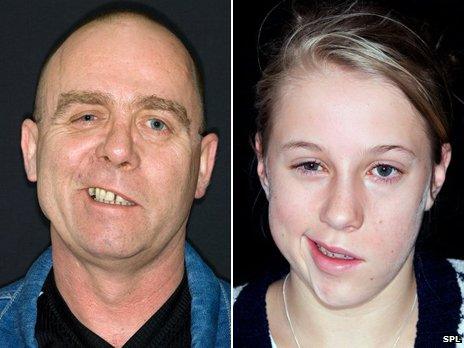

Bell's palsy sufferers: Most eventually recover from the condition

The illness, he believes, is all too often dismissed by the medical profession as a cosmetic issue because there are no ill effects apart from the paralysis.

But Mr Nduka has seen the huge toll it can take. One patient, a professional musician, is no longer able to make the mouth movement needed to play the saxophone. Another, a receptionist, is simply unable to carry on in her job facing the public. In my previous article I mentioned one father permanently stripped of the confidence to appear in a family photograph.

As one of the UK's leading experts in the treatment of the condition, Mr Nduka says that there are a few vital rules for doctors to follow when dealing with new cases:

They must prescribe a course of prednisolone steroids as early as possible unless there is a good medical reason not to

They must not recommend forceful or unsupervised facial exercises as this may lead to abnormal facial movements after recovery

Patients who have not recovered fully within six weeks should be referred for further expert advice

The affected eye must be treated with eye drops during the day and taped shut at night to prevent serious damage

Of course the two questions any new Bell's palsy sufferer wants answered are, "Will I get better?" and "How long will it take?"

The good news is that most people make a full recovery - many within a matter of weeks. Something like 70% of sufferers are back to normal within the space of a year. Getting the course of steroids in time will increase your chances of finding yourself in this happy category.

Even without steroids, as my own case shows, most people get back to normal. The doctor I saw did not prescribe them and, by the time I realised how important they were, it was too late. I'm left wondering though whether my recovery might have been faster and fuller if I had been given them.

I'll never know, because while steroids increase your chances of recovery they don't guarantee it. Estimates suggest that up to 30% of sufferers will be left with some residual effects more than a year after the onset. Five per cent of sufferers will experience after-effects that are severe and long lasting and, as a result, face the possibility of serious psychological distress.

"It may be even harder nowadays," Mr Nduka says. "Face is everything - Facebook, Facetime, Skype. We live in a very image-conscious age."

As for me, well I'm almost back to normal, as you can see from the video. I've been left with a tiny bit of asymmetry and a slightly weaker blink in my left eye. But recovery can continue for up to 18 months and the blink, being at the furthest extremity of the facial nerve, is often one of the last things to return. Anyway, I'm not complaining.

So a big thank you to all those who wrote with words of encouragement, advice and good humour. You made a difficult 12 months so much more bearable. And on behalf of those whose recovery is still slower and less complete than they'd like, a humble appeal to medical science to do a bit more.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external