A Point of View: JFK and the rise of conspiracy theories

- Published

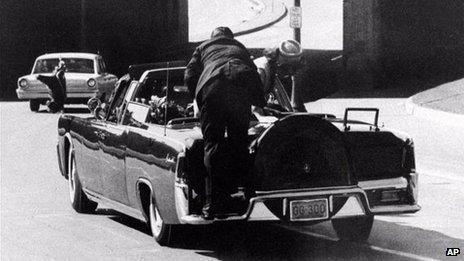

With the 50th anniversary of John F Kennedy's assassination approaching, Will Self wonders if this was when Westerners started to distrust official accounts.

In Dealey Plaza the light quality was dun-to-sepia and the jackhammers of the highways department drumming on the sainted tarmac seemed to presage some terrible event yet to happen.

Near to the workmen were two white crosses painted on the tarmac.

Pointing them out to me, a ragged and quite possibly homeless man explained that the first marked the spot the president's motorcade had reached when the first of the assassin's bullets hit, while the second cross marked the entry point of the second bullet.

Another destitute man who was sauntering past snarled out of the corner of his mouth: "Don't listen to him, he's working for the government."

A white cross marks the spot where JFK was shot

I resisted the urge to quip, "Well, if he is they certainly aren't paying him enough," because, standing on the grassy knoll, within yards of where John F Kennedy met his end, and within days of the half-centenary of this momentous event, levity hardly felt appropriate.

But then this begged the question - what is the appropriate way to commemorate a political assassination?

Taken as a collectivity - which, after all, is often how Americans wish to be considered - their response to this conundrum has been curiously muted.

On the evening of the day I explored Dealey Plaza and its environs I spoke with an academic at a local college who - like so many others - vividly remembered that day in November 1963.

A child growing up in a mixed Irish and Mexican-American, North Dallas blue-collar neighbourhood, she recalled the people coming out of their houses to stand, many weeping uncontrollably, in their front yards.

"In their homes," she told me, "they would have two iconic portraits. Images painted in profile, in garish oils on black velvet backgrounds. One would be of the pope, the other of Kennedy."

The years, and now the decades of lubricious revelations have tarnished John F Kennedy's once coruscating lustre, and standing in the overcast plaza I couldn't help but see a parallel between this and the way the prospect before me - such a cramped, workaday urban space - contrasted with the mythic realm depicted by Abraham Zapruder's infamous film of the assassination.

Zapruder's footage became emblematic of the growing mediatisation of public events in the 1960s.

A decade that began with disasters still happening in far away countries of which we knew very little and saw virtually nothing, ended with the emaciated stick-figure victims of the Biafran war lolling listlessly on our television screens, intercut with near-live film of US Army helicopters strafing Vietnamese villages with heavy-calibre machine guns.

Kennedy's assassination was the epitome of this new phenomenon, fitting as it did celebrity, glamour, tragedy, bloodshed, sex and power within the compass of a single lens.

And then there were the conspiracy theories. In back of the knoll itself - which is actually a crescent-shaped verge of modest proportions - I found local historian Mark Oakes beside his rather permanent-looking stall. A tall, well-preserved man, with a full head of dark hair, cut Kennedy-like en brosse, Oakes had, he told me, become fixated when in 1971, still a high school senior, he had read right through the many fat volumes of the Warren Commission's report into the assassination.

Forty-two years later, he shows the Zapruder film on a portable DVD player along with clips of his own TV appearances. He also has an array of books and pamphlets available and, without any soliciting on my part, he quickly offered to sell me copies of the president's autopsy photographs "autographed" - as he put it - by one of the technicians who had assisted.

Yet the surprise for me wasn't this macabre obsessiveness but Oakes's response when I asked him, "Come on then, who did it?"

Because instead of coming out with one or other of the myriad conspiracy theories that have rooted over the years in the psychic mulch formed by so much tortured regard, he instead shrugged his shoulders and replied, "I dunno, there are so many possible candidates: the mob, the CIA, the Teamsters - you can take your pick."

Mark Oakes manning his stall

When I taxed him: "But you do believe there was a conspiracy, don't you?", he continued, "I would say a cover-up, definitely - but I don't know about a conspiracy."

In fact, as we continued talking, it became clear that Oakes's main evidence for the assumption that the real character of this momentous event had been wilfully obscured was his own disbarment from its mediatisation.

"They never have me on NBC or any of the other major networks," he said, his rich baritone rising slightly into moan.

Heading into the former Texas School Book Depository, which now houses, in the very place from which those shots were allegedly fired (its sixth floor), a museum dedicated to the assassination, I reflected on how it was that Oakes personified the relationship between the individual and history in the era of mass media.

Both conspiracy and cover-up are nostrums designed to reassure us that our feelings of powerlessness and irrelevance are justified. How can we be expected to do anything about these dreadful things that are happening right in front of our eyes if they simultaneously lie to us and refuse to let us have our say?

The museum was muted and tasteful.

We had been warned by the youth at the ticket desk not to take any photographs. What Oswald may - or may not - have seen through his rifle sights has now been copyrighted by the Associated Press. Naturally, I ignored this.

The view from the sixth floor window an hour after Kennedy's assassination

As for the window from which Oswald just might have shot the white hope of American democracy, from an adjacent one I looked down at the white crosses in the roadway at a steep angle through tree foliage.

For a historic distance it seemed a small one - a model of the trajectory rather than the trajectory itself. The actual window had been glassed off and transformed into a tableau mordant of how it might have looked 50 years ago, complete with repositories of musty school text books.

Walking across downtown Dallas I mulled over with my two companions - both American, one a native Texan - the strange sense I had that the museum had done its job.

Even the Jackie Kennedy replica pearls in the gift shop and the ashtrays inscribed "Carpe Diem" played their part, for in commodification - this being America - there was also a certain historicity.

The gift shop inside the JFK museum

The assassination, I said, now seems to belong definitively to the past, rather than to some Zapruder film-loop of the permanent present.

Mike, the Texan, said he thought that this might be true, and instanced the fact that the man who once plied a trade driving tourists around the plaza in an open-topped Lincoln limousine, seemed to have hung up his ignition key.

"When he drove over the Xs, a tape recorder in the car played realistic rifle shot effects," Mike said.

Fifty is a lot of years, and before the elongation of western lifespans would have been accorded a couple of generations.

Belying Oakes's youthful appearance, the fact remains that what's been covered up for him is not what's been hidden from contemporary Americans. In a year that saw the exposure of the National Security Agency's tentacular sucker-prints all over the VDUs of the wired world, the half-century-old arguments about whether the camera ever lied begin to seem hopelessly recondite.

It isn't so much, I think, that the Kennedy assassination has transitioned smoothly into a commonsensical past. It's rather that it is the first instance of a peculiarly modern variant of the historic event - its media simulation.

Since that November day in Dealey Plaza, the generality of Westerners have ceased, in an important way, to lend credence to the effusions of the media. Far from believing that the camera never lies, we suspect that like our political leaders, it always does.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external