Mandela liberated South Africa - and me

- Published

The Mandela family had to cope with a double strain through the long years of Nelson's imprisonment - dealing with its own private distress, while trying to maintain a defiant yet dignified public face in the anti-apartheid struggle. My relationship with the Mandelas began much earlier, and it had little to do with politics.

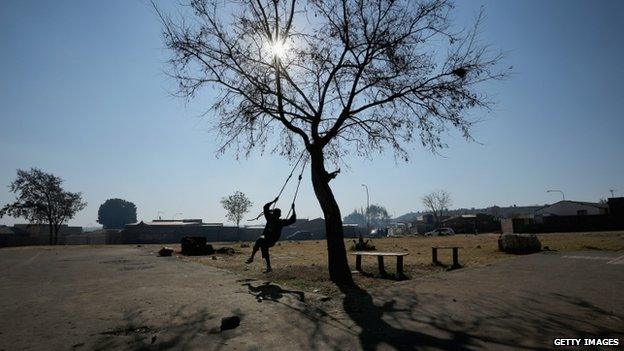

In the 1980s, while Nelson Mandela was serving his life sentence on Robben Island, we were roaming the streets of South Africa's largest township Soweto, his shadow looming large over us.

No-one dared mention his name but we were all constantly thinking about him.

Soweto is an apartheid creation, a cluster of mini townships.

Mine and Mandela's is called Orlando West. This is where I spent my formative years at the height of whites-only rule.

Just the mention of his name could land us in prison.

The white minority regime just could not comprehend why so many people around the world were calling for the release from jail of a man they called a terrorist.

But according to the people of Soweto and the wider world, he was a hero.

Winnie Mandela was determined to keep his name alive. She opened her house to all sorts of people, as long as they were fighting for the liberation of black South Africans from the brutal oppression.

I was not one of these activists who frequented this self-declared headquarters of the African National Congress.

I went to the house as a neighbour and because I was a friend of his daughter Zindzi.

She and her mother were not only black South Africa's first family, but they were beautiful too. They invoked the same sort of feeling most Africans have when they see Michelle Obama and her children.

They were likeable. Everybody wanted to be associated with them.

We lived close by. My late father's home is 8182 Lembede Street, near the junction with Vilakazi Street.

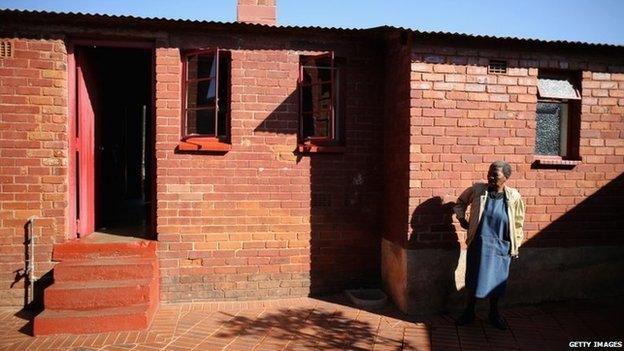

The Mandela family home, now a museum, is 8115 Vilakazi Street. It's a small four-room house, made of red brick - typical of the area.

And this was the place he returned to after being freed from prison. He wrote about it in his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom.

"Number 8115 in Orlando West was the centrepoint of my world," he wrote, "the place marked with an X in my mental geography. When I saw it again, I was surprised by how much smaller and humbler it was than I remembered. But any house in which a man is free is a castle when compared with even the plushest prison."

Another person keen to keep Mandela's name alive was our history teacher Mr E S Hlubi. It was his job to teach us the heroism of the white Dutch settlers in the 17th century.

Led by Jan Van Riebeeck, they arrived in a ship named Dromedaries at the Cape of Good Hope, on the southern tip of the African continent.

In middle of this lesson our teacher, a tall hefty Zulu man with a deep voice, suddenly stopped and whispered to the whole class: "There's another man whose name we should never forget, his name was Nelson Mandela."

He told us that if we mentioned one word of this conversation he would kill us. This part of the lesson may have lasted only a minute but it stayed with us forever.

Mr Hlubi was not alone.

My father, Henry Mthenjwa Nkosi, once told us to listen to a song by Miriam Makeba and Harry Belafonte entitled "Bahleli bonke etilongweni, bahleli bonke kwanogqongqo".

It means simply: "They're all languishing in jail."

Winnie Mandela's home was an unofficial headquarters for the ANC

This song was about Mandela and his comrades, and the entire album had been banned by the apartheid authorities. It was illegal to listen to this album.

So when Mandela was released in February of 1990 and returned to 8115 Vilakazi Street, I was among the crowds there too.

I was happy for him. And when he finally touched my hand in a brief handshake, it was a dream come true.

A dream that began in the dusty streets of Orlando West many decades before. I thought of that line in a Bob Marley song: "In this great future how can we forget our past?"

Then on 10 May 1994, I attended his inauguration as South Africa's first democratically elected president.

Again, not only was I happy for him because he did a fantastic job of negotiating himself out of prison and eventually delivering freedom for his people, but because in the process he liberated me, too.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external