America's new Irish immigrants

- Published

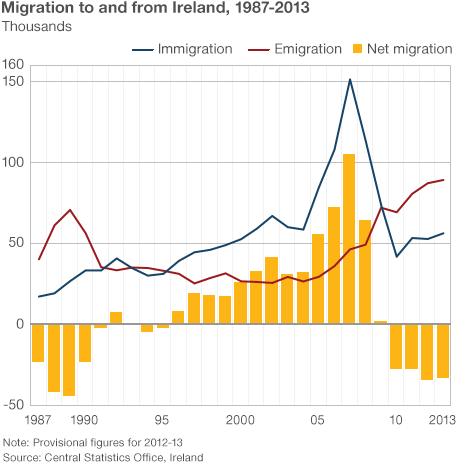

Ireland may no longer need bailout money as its economy emerges from recession, but a wave of emigration that began in 2008 is continuing. And as in the 1980s, many thousands of those moving to the US may be becoming illegal immigrants.

Of America's Irish neighbourhoods the one that spans the border between the Bronx and Yonkers in New York may be the most colourful.

Old-fashioned Irish bars line the road. Grocery stores offer boiled bacon, oatmeal and tea. The Shamrock Gift Shop sells woollen sweaters, Waterford crystal, and statuettes of angels holding Celtic crosses.

Irish immigrants have been settling in the area for decades, driven by recurring economic crises back home. On the main streets, Irish accents predominate.

As immigration controls have gradually tightened it has become harder to make the journey. But unemployment, falling salaries, and poor career prospects have been prompting more Irish people to cross the Atlantic, some of them drawn to this Irish community.

"It was kind of a surprise to me," says Megan, 20, who followed her boyfriend over three months ago from Dublin and found work in an Irish cafe in Yonkers.

"When I'm around this area on nights out it doesn't even feel like I'm in America. It literally feels like I'm back home because there are just so many Irish people."

If it hadn't been for that community, Megan says homesickness might have prompted her to return to Ireland, but now she's planning to stay as long as she can.

"Every time I ring my Mam, she's like, 'don't bother coming home - nothing has changed so there's not much point.'"

Figures on Irish immigration to the US are hard to find, because many, like Megan, come as tourists and then begin working in the informal economy.

In Yonkers, men hunched over pints of beer in half-empty pubs say there are far fewer people arriving now than during the last big wave of Irish emigration, in the 1980s.

But those working with immigrants in major cities including New York, Boston, Chicago and San Francisco have noticed a sharp rise in arrivals over the past two or three years.

According to Ireland's Central Statistics Office, external, nearly 20,000 people moved from Ireland to the US between April 2010 and March 2013 - more than double the figure for the three previous years.

At the Yonkers branch of the Aisling Irish Community Center, director Orla Kelleher says there has been a "huge upsurge" - perhaps 10 times as many new arrivals in the area as there were a decade ago.

Most are young, though some older people, in New York and elsewhere, have emigrated twice, returning to Ireland from the US while the Irish economy was booming before retracing their steps when it crashed.

A majority of those seeking assistance at the Aisling Center had work in Ireland but many were worried about losing their jobs or having their hours cuts.

The choice of destination "may be down to [Ireland's] long-standing historical connection with the United States, as well as having actual physical connections here through family and friends", says Kelleher.

Irish immigration to the US peaked in the mid-19th Century, around the time of the famine. By 1855 there were 200,000 Irish living in New York, and they remained the largest foreign-born community in the city for 30 years. Many others settled in Boston, and elsewhere on the East Coast.

Some 70% of those emigrating from Ireland now are in their 20s, according to one recent study, which also found that they had higher than average education. But Niall O'Dowd, an Irish journalist and immigration reform campaigner based in New York, says they don't always find good jobs.

"A lot of them are very highly educated, smart people but they find pretty working-class jobs like construction and bar-tending here, because that's where the [Irish] network leads them and they're not able to break out of that."

Unless they are lucky enough to win permanent residency in a green card lottery, those who want to emigrate either have to find an employer to sponsor them before leaving, or come across on a J-1 visa for students or recent graduates.

There is a 90-day J-1 visa that allows students to work in the US during the summer holidays, and a year-long J-1 that requires graduates to find a job related to their degree.

Richard Burke came twice on J-1 summer visas - he worked as a "glorified gardener" in California in 2009 and as a barman in Chicago in 2012. Then in August he moved to Philadelphia, after graduating in chemical engineering from University College Dublin.

Now employed by the state of Delaware, he's hoping to transfer to a longer-term visa and then apply for a green card. He wants to live indefinitely in the US, where he likes the "big city feel" and finds the job prospects more enticing.

Although Americans "accept you with open arms", he says the Irish connection can be crucial.

"You need to know somebody to actually get your foot in the door, because most corporations will see that all visas come with is more paperwork, trouble and hassle."

Burke, 23, gets moral support and encouragement from older members of Philadelphia's Irish community.

"They just see a younger version of themselves coming over and trying to make a living and trying to do exactly what they've done," he says.

Danielle Allen, 26, also came out on a J-1 visa. She has a masters degree in business marketing, but had found herself working at the front desk of a hotel at home in County Cork.

She thought of going to California, where she had spent a summer as a student, but a cousin in Chicago persuaded her to head there instead. She found work at Chicago Irish Immigrant Support, and a large group of Irish friends who have also arrived in the last couple of years.

The Irish "stick together", she says. "There's a huge Irish community here and everyone tries to help people coming out with finding accommodation, jobs.

"If you just wanted to be involved with Irish only, you could definitely eat, sleep and drink Irish here if you wanted to."

Sticking together - Danielle Allen (fourth from right) with friends in Chicago

Graduates in Chicago commonly go to social gatherings organised by the local Irish network on the first Friday of each month to seek out jobs.

But it is those without documents who are most dependent on the Irish community, using it to find a place to stay and a job that pays cash-in-hand.

In many places the Gaelic Athletic Association, which runs Gaelic football and hurling leagues, has replaced the Church as a first port of call, says Breandan Magee, director of Chicago Irish Immigrant Support.

Irish immigration centres say there are an estimated 50,000 undocumented Irish living in the US, and that most of those who have arrived recently fall into this category.

A recent report, Emigration in an Age of Austerity, external, argues that it is not "a feasible option" for most to remain in the US with undocumented status, but it notes that only 10% of Irish emigres who were surveyed in various countries said they intended to return to Ireland once their temporary visas expired.

After large numbers of Irish arrived in the 1980s, powerful Irish-American politicians managed to negotiate special visas for tens of thousands of immigrants.

The Irish would be granted 10,000 similar visas under an immigration reform bill backed by President Barack Obama, but there is little hope the measure will pass soon.

That means undocumented immigrants feel stuck, unable to go home for family weddings or funerals for fear they won't be let back in. Obtaining a driving licence or health care is also a problem. And many are anxious, worried about the risk of deportation if they are stopped by the police.

Conor, 27, has been living like this since he emigrated in 2010 from County Armagh, just over the border from the Irish Republic in Northern Ireland.

He left because he "had no friends left at home and nothing to do", and came to work as an electrician for his brother in Chicago.

"For me it's just been really tough, because I can't go home, I'm constantly watching over my shoulder," he says.

Having missed three Christmases, he is thinking of heading back this year - and then on to Australia.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external