The fall and rise of mannequins that look like real women

- Published

Shoppers browsing 2014's spring and summer collections will see clothes displayed on size-16 mannequins. It might sound unusual in a modern fashion industry obsessed with slender frames, but down the years the figurines' shape has varied considerably.

They stare vacantly out of the shop window, adorned with the latest trends - the silent figures of fashion.

But they are not just vehicles for the fashion industry to showcase their creations to potential customers. Mannequins communicate more than we might think about attitudes to body image in any given era.

With the average British woman now a dress size 16, Debenhams has decided to introduce larger mannequins into its stores to reflect the shape of many of its customers.

It's a significant move as mannequins have typically symbolised what the fashion industry thinks its customers would ideally like to look like in their clothes, rather than how they might actually look.

According to Oriole Cullen, acting senior curator of fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, shop mannequins are "incredibly revealing when it comes to scrutinising fashionable or desired body shapes in any one particular period".

Most female mannequins we see in the shops today are typically a UK size 8-10, 5ft 11in (1.80m) tall, 34B bra, 24/25in (61/64cm) waist, 36in (91cm) hips and 32in (81cm) inside leg with a 3/3.5in (8cm) heel, according to Tanya Reynolds, creative director at mannequin manufacturer Proportion London.

For men 6ft 1in (1.85m) tall, a 40in (102cm) or 42in (107cm) regular suit, with a 38/40ins (97/102cm) chest, 30/32in (76/81cm) waist, and a 32in (81cm) inside leg is standard, as many clothes stores work to set measurements.

Most male and female mannequins on the High Street today are a standard size

According to Reynolds, the current mannequin trend for men is a slimmer shape, whereas for women there has been a recent move towards a figure that is bigger on the waist and more natural.

It is not the first time that a broader range of body shapes has appeared in shop windows.

In the 18th Century, fashion dolls would be used by couturiers, or fashion designers, to display the latest styles to royalty says Eleanor Thompson, who is studying for a PhD in the display and interpretation of dress collections, and is a former curator of dress and textiles at Brighton Museum and Art Gallery.

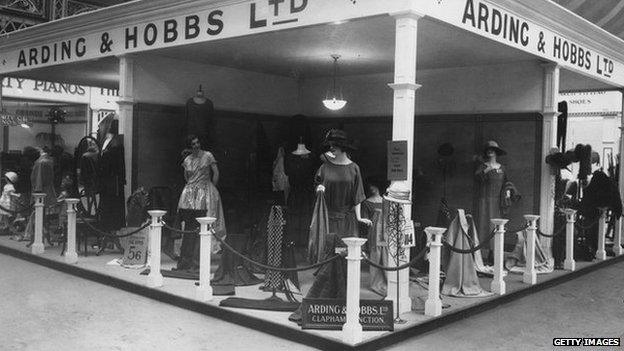

Yet it was the expansion and growth of small drapers' shops into large city department stores in the 19th Century that really brought the mannequin to life.

The luxurious shop windows in the department stores would entice customers in to buy

"Department stores began to have large plate glass windows overlooking the streets and a whole massive industry of shop merchandising grew up around creating very narrativised scenes, which would encourage passers-by to imaginatively identify with the clothes that were on display," says Thompson.

In these stores mannequins would be placed within idealised settings, appearing as passengers on a cruise liner for instance, so that shoppers could aspire to a world of luxury.

According to Cullen, the mannequins in this period were designed to be as lifelike as possible.

"Early shop mannequins often had glass eyes and their heads were made with wax and finished with wigs to try to achieve a realistic effect," she says.

In the early 20th Century, this realism also extended to the shape of the mannequins' bodies, says Thompson, and it wasn't only the period's ideal body shape that was represented.

"In the early part of the 20th Century there was a much broader, more diverse range of body types, so you would find ideal types, but you would also find every kind of shape and personality represented," she says.

Reynolds says larger-shaped mannequins were a hangover from the Victorian era, where carrying more weight was a sign you could afford to eat well.

Female mannequins from the early 20th Century had more rounded chests and straight hips

Pierre Imans, a French mannequin manufacturer of the period, made wax mannequins for department stores worldwide and gave his mannequins personalities and names such as Elaine, Roberta and Nadine.

"The Pierre Imans mannequins are actually quite flat-chested, but they've got almost a pear shape to them, quite wide hips," says Thompson.

"It gives you a much more realistic and more nuanced perspective about real women's body shapes and how actual fashions looked on real body shapes, so how the 1920s dresses would actually hang on a figure that wasn't stick-thin."

Shop mannequins were larger and more realistic in the 1920s

Imans's male mannequins also showcased a variety of physical types and facial expressions and he produced three female mannequins that were a size 46 or UK size 18 and looked middle aged, says Thompson.

However, by the mid-20th Century, female mannequins had started to become more uniform in size and shape and embody the period's ideal notion of the perfect female form, something that varied from decade to decade.

Mannequins in the 1950s had defined waists - inspired by filmstars such as Audrey Hepburn

"Figures from the 1950s have tiny, defined waistlines, rounded hips, high, pert busts and sloping shoulders," says Cullen.

"In more recent eras, such as the 1990s, a toned body with narrow hips and a straight shoulder line was popular."

In the noughties, Reynolds says larger breasts on slim mannequins became increasingly prevalent on the High Street, partly due to the uptake of cosmetic surgery.

The popularity of cosmetic surgery has led to an increase in mannequins with bigger breasts

When designing a new mannequin collection, the client's requirements, target audience and set of measurements are the starting point, says Reynolds. A human model who fits these particular criteria and embodies the style is then chosen for the sculptor to refer to. A mannequin that looks wooden has probably not been sculpted using a model, says Reynolds.

Although the materials used to make shop mannequins have changed from wax and plaster in the early part of the 20th Century to more hard-wearing plastic and glass fibre, Cullen says their actual structure has changed very little over the years.

"In general because of the cost of production and their size, mannequins tend to be quite uniform in size and shape, so it's interesting to see that increasingly retailers are rolling out a more diverse approach to their display figures," says Cullen.

At a time when many campaigners are calling for greater diversity across the fashion industry, Dr Sarah Riley, senior lecturer in the psychology department at Aberystwyth University, says mannequins should reflect the diverse body shapes and sizes of the 21st Century.

The weird world of a mannequin factory

She has conducted research into how we see ourselves in relation to our bodies, gender and appearance, and has worked with the Government Equalities Office looking at body confidence, external.

"I think there has been an incongruence between what the advertising industry think people want to look at and what people actually do want to look at. So I think that's been part of the shift with the mannequins," says Riley, who says recent research has shown that people want to see models and figures that look more like themselves and be told that is beautiful. This call for greater diversity also extends to the range of ethnicities represented on the High Street.

Riley says that anything that allows people to recognise that they can be healthy and beautiful at any size is important in a culture which is highly judgemental about body size.

Some commentators on internet forums have claimed that larger mannequins could promote obesity, but Riley says introducing a size 16 mannequin into shops is not encouraging women to aspire to an unhealthier lifestyle.

Equalities Minister Jo Swinson has welcomed the move to introduce size 16 mannequins into shops

"I would love us to be less fixated on weight - because all it does is create a bullying culture - and much more fixated on being healthy, feeling healthy, doing the things that are associated with allowing us to feel good inside our bodies," says Riley.

She says we can chart through history our concept of the ideal body using other replicas of human beings and that, like women, men are also subjected to subconscious social pressures.

This can be seen in cultural artefacts such as the male Stars Wars figures, which have changed from their regular build in the 1970s to a He-Man-style shape today, while young boys dress up in superhero outfits that have a built-in six-pack, teaching them at a young age that their bodies are not good enough, says Riley.

With the average British person far from the superhero body shape, it will be interesting to see how far the High Street will go in its attempts to reflect the shapes of mere mortals.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published6 November 2013