China and Japan: Seven decades of bitterness

- Published

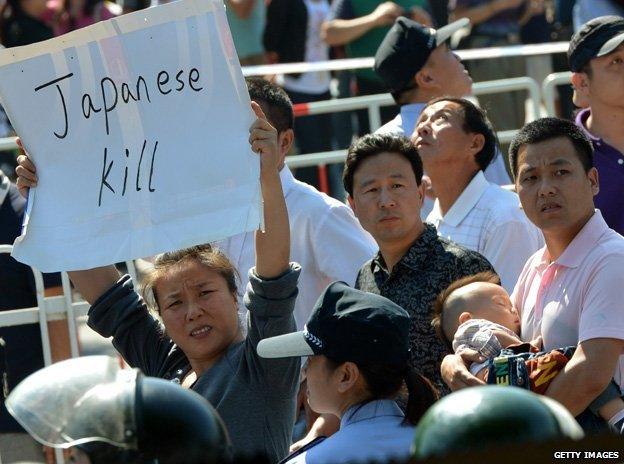

A woman holds up an anti-Japanese sign during a protest in September 2012

A dispute over islands in the East China Sea has inflamed relations between Japan and China for the last two years - but they were tense even before. The BBC's Mariko Oi visited both countries with a Chinese journalist to find out why the wounds of World War Two refuse to heal.

"Do you feel guilty about what Japan did to China during the war?" It was a question that I had to translate more than once during a trip to Japan with Haining Liu, a former reporter for China's state broadcaster, CCTV.

It was Haining who posed that question to some of our interviewees - the oldest of whom would have been a child in 1945.

"I feel sorry for what happened," said one man. "There were many regrettable incidents," said another.

"But maybe my regret isn't enough?" added one of them, a Japanese nationalist, who argues that most school textbooks exaggerate the abuses carried out by Japanese soldiers. "No," Haining responded. "It's not enough."

There are some undisputed facts. Japan was the aggressor, occupying Manchuria in northern China in 1931. A wider war began in 1937, and by the time Japan surrendered in 1945, millions of Chinese had died.

A notorious massacre occurred in the city of Nanjing, which was the capital under the Kuomintang government. Atrocities were also carried out in other Asian countries.

But it made me feel uncomfortable every time I had to translate the word "guilt" into Japanese. And none of our Japanese interviewees would use it.

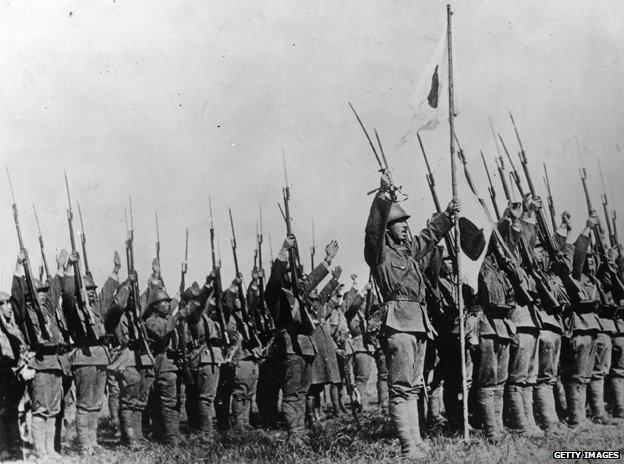

Prisoners of war in Manchuria, 1931

Should today's generation bear the responsibility for past mistakes?

I put that question to Haining on our second day together, asking if she thinks I should also feel guilty. She didn't say "Yes" or "No".

"I will keep asking the question while I'm here," she said. "Because that is how many Chinese people feel."

I personally became interested in the history of World War Two as a teenager. Over the years I have researched the topic quite thoroughly. Many of my holidays have included a trip to war museums across Asia, in an attempt to understand the damage and suffering Japan caused.

I have long felt that I was not taught enough at school, so last year I wrote an article about the shortcomings of Japan's history education. It pointed out that the syllabus skims through more than a million years of Japan's relations with the rest of the world in just one year of lessons. As a result, many Japanese people have a poor understanding of the geopolitical tensions with our neighbours.

My article made many people in my home country, including some of my own family, uncomfortable.

It was not a foreigner criticising Japan, it was a Japanese reporter openly criticising Japan in front of global audience.

"Traitor" and "foreign spy" are just two of the many names I was called. "Don't you love your own country?" one person asked on Twitter. Of course I do.

When I confronted Japan's past, it was like experiencing a bad breakup. I went through similar stages - shock, denial, anger and sorrow. I eventually came to accept that I could not change what had happened.

Japanese soldiers celebrating, 1941

But especially after watching violent anti-Japanese protests in China in 2012, I wanted to ask two questions.

Is there anything we can do to improve our relationship? And why don't other Asian countries, where the occupying Japanese army also killed many civilians, hate the Japanese as much as China and South Korea do?

"Hate" may be a too strong word - but it seemed to me to describe the feelings of Chinese protesters who were burning Japanese cars.

This isn't how Haining sees it. When she grew up in the 1980s and 90s, Japanese pop culture - music, drama, and manga - was popular with young Chinese people. She and her friends, she says, had a positive attitude towards Japan.

"But I cannot speak for every Chinese person, 1.3 billion of us, for China is a vast country, and people are entitled to have their personal feelings," she says.

"For example, among those who lost close family members because of Japan's invasion, or among those who actually suffered a great deal during the war, hostility or even hatred might still remain. They shouldn't be judged because of that."

Singapore, where I've lived since 2006, also suffered at the hands of Japanese soldiers, but there have not been anti-Japanese protests there for decades.

Different sources cite different numbers of casualties, but 50,000 to 100,000 ethnically Chinese Singaporeans are believed to have been killed in what is known as the Sook Ching massacre. In a small city state of some 800,000 in 1942, that is a huge number.

I met a relative of one victim at the Civilian War Memorial on Beach Road.

"I don't blame today's generation," said Lau Kee Siong, to my surprise. I asked him why he was so much less angry than those Chinese protesters.

"We are a country of immigrants so our basic philosophy is that we must survive," he said.

"When we became independent from Malaysia in 1965, the general assumption was that we had about three years before we would have to crawl back into Malaysia. So when Japan came along and offered financial support and investments, the most logical thing was to accept them instead of criticising what they had done to us in the past."

At about the same time, I also found out that some relatives of one of my closest friends, Jade Maravillas, had been killed under the Japanese occupation in the Philippines. Even though we had been friends for years, she had said nothing about it until she read my article because she thought "it may make our friendship awkward".

"Many people including my great uncles and aunts were staying at De La Salle University during the war," she said.

"The Japanese soldiers raided the school and my great uncles were killed. One of the aunts was stabbed but survived and showed me her scar when I was a teenager."

I wondered if she held any grudges against the Japanese. "Didn't you think about your relatives when you first met me?" I asked.

"Are you kidding me? My partner is half-Japanese," she laughed. "And it's not your fault."

I asked Jade too if she could explain why her views about Japan were so different from those held by many Chinese.

"I'm not sure," she said. "But to us, Japan was just another colonial power after the Spanish."

In fact, China also seemed to be heading towards a pragmatic relationship with Japan in the 1970s, under Chairman Mao Zedong, when the two countries restored diplomatic relations.

"Chinese Communist propaganda at the time emphasised the victory of the communist side during the Chinese civil war," says Robert Dujarric, director of Temple University's Institute of Contemporary Asian Studies - referring to the war between Mao's Communists and nationalists under Chang Kai-shek, which lasted until 1949.

A Japanese monk visits Chongqing in 2006, to apologise for war crimes

In 1972, when the then Japanese Prime Minister, Kakuei Tanaka, apologised for what Japan did during the war, "Chairman Mao told him not to apologise because 'you destroyed the Kuomintang, you helped us come to power'," Prof Dujarric says.

But the Party's propaganda seems to have taken a turn towards nationalism after the Tiananmen Square massacre, in which the Chinese army crushed to death students who were demanding democratic rights, on 4 June 1989.

"Before the 4 June, it portrayed the Communist Party as victorious and glorious - it defeated the nationalist Kuomintang army in the civil war. But after 4 June, the government started emphasising China as a victim," says Prof Akio Takahara, who teaches contemporary Chinese politics at Tokyo University.

The Communist Party now casts itself as the party which ended a century of humiliation at the hands of outsiders, he says.

"And the way they do it is to breed hatred against the most recent invader and aggressor."

Switching on the television in my Chinese hotel room, it was easy to find television programmes dramatising China's resistance to the Japanese invasion. As part of the country's "patriotic education" policy, more than 200 were made last year.

We spoke to an actor who "died" eight times a day, playing the role of a Japanese soldier in countless anti-Japanese dramas.

Had I grown up watching them, I would probably conclude that Japan was a horrible nation.

A similar message seemed - at least to me - to be contained in an assembly we observed at a primary school in south-western Beijing. A succession of young children led the group in song, rhymes and martial arts. One of the poems was about an incident at the nearby Marco Polo Bridge in 1937 - an event seen by many as the start of the last war between China and Japan.

Is this message about Japan justified? I am honestly torn. As we visited different parts of China and spoke to survivors of Japan's atrocities, my heart ached.

One survivor was Chen Guixiang, who had been a 14-year-old girl in Nanjing in December 1937, when the massacre took place.

Dead bodies were piled up outside a school, she said. She witnessed a girl of her own age being raped by seven Japanese soldiers, then killed with a knife.

Twice she was almost captured and raped herself - only escaping, on the second occasion, because the soldier carrying her slipped and loosened his grip. She ran until she collapsed with exhaustion and was hidden by a Chinese farmer under a pile of grass.

Chen Guixiang remembers bodies being piled up outside her school

It was a bitter experience to listen to such accounts of the actions of Japanese soldiers. The one small crumb of consolation in Chen Guixiang's story was a postscript. Years later, when she travelled to Japan to recount her experiences, people hugged her and apologised, saying they had no idea their ancestors had done such things.

Japan's leaders have also apologised to China many times.

Ma Licheng, who used to write for China's state-owned People's Daily newspaper, says he has counted 25 apologies from Japan to China overall. But none of these - nor Japan's financial aid to China, amounting to 3,650bn yen ($35.7bn; £21.8bn) over the years - have been covered in the Chinese media, he says, or taught to children at school.

"What Japan did in China during the war was horrible," Ma wrote in his book Beyond Apologies. "But demanding that they kneel on the ground is pointless. The wording of the Japanese apologies may not seem enough to us, but to them, they were a huge step so we have to accept them and move on."

When he published his book, he was called a traitor - a response he describes as "normal", given the emotions the subject stirs.

Haining confirms that she was not taught about these things at school. On the other hand, she doesn't think it would make a big change to Chinese attitudes towards Japan, even if children did learn about them.

"Changing public attitude takes time, several years or maybe a decade. Thus, it is also up to Japanese leaders to keep a consistency in their actions and words," she says.

"People might feel favourable towards Japan after knowing more about Japan's apologies in the past, and economic contributions.

"However, one statement denying the existence of the Nanjing Massacre, or similar intentions to glorify war crime, would destroy the trust immediately, and it would take much longer to rebuild that kind of trust again."

In 2012, the mayor of Nagoya, Takashi Kawamura, a prominent nationalist, denied there was a massacre at Nanjing, saying there were only "conventional acts of combat". Last year, he made clear his views had not changed.

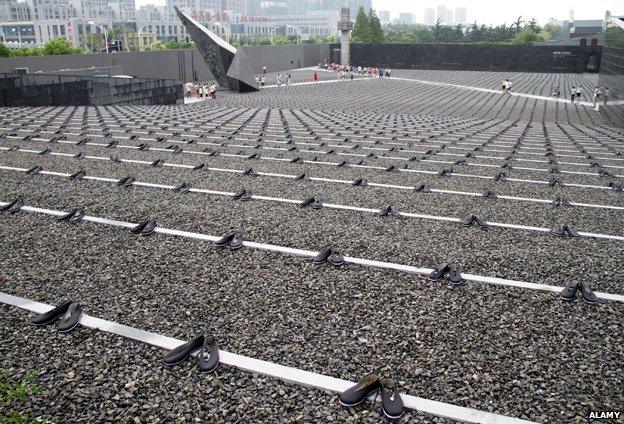

Thousands of pairs of shoes are laid out at the memorial to the Nanjing Massacre

It also infuriates China and South Korea when Japanese leaders visit the Yasukuni shrine, which honours the country's war dead - among them convicted war criminals.

It's hard to see this kind of thing coming to an abrupt halt.

At the end of our trip, I was pleased that Haining answered the question I posed on day two. She said she didn't think I should personally feel guilty.

But we both felt less optimistic about our nations' future relationship than we had when we set out.

It still troubles me that generations of Japanese children have learned little about the atrocities our forefathers committed in China. And that young Chinese people don't know that our nations had begun to put the war behind them in the 1970s and 80s - until Tiananmen Square.

Haining sees no chance of reconciliation "if leaders in both countries keep adopting the current policies against each other".

"We have a chance to improve relations, at least, on the public or grass-root level by increasing honest and open conversations," she says.

"War is not an option, despite how difficult it is… We must try everything possible."

Listen to the first part of Missing Histories - China and Japan on the BBC World Service, on Saturday 15 February

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external