Woolwich: How did Michael Adebolajo become a killer?

- Published

The two men who killed Fusilier Lee Rigby in Woolwich have been sentenced for the murder. Their journey towards violence is still being unravelled.

Michael Adebolajo never expected to see his 29th birthday. But he did - and it came the day after he told an Old Bailey jury he wished police had shot him in the head.

As he lay bleeding from a bullet wound in his arm, sprawled on the carriageway at Artillery Place, yards away from the mutilated remains of Fusilier Lee Rigby whom he had just killed, Adebolajo was still trying to deliver his message.

"Please let me lay here," he moaned as a paramedic assessed his wounds. "I don't want anyone to die. I just want the soldiers out of my country."

Morphine dulled the pain of a bullet hole in his bicep. He decided to give the ambulance team his arm. He mumbled that Allah had given it to him and now it was theirs.

Armed police surround Adebolajo

"I wish the bullets had killed me so I can join my friends and family."

Adebolajo's original friends and family were not in the forefront of his mind the day he cut down a man on the streets of London.

He came from a Christian family in Romford on the border of London and Essex. He had plenty of white friends, one of whom was Kirk Redpath, an Irish Guard who was killed by an insurgent's roadside bomb in Iraq.

Like his co-defendant, Adebolajo's family were hard-working Nigerian immigrants.

His parents would take him to church every Sunday and he was taught by his mother how to pray. He learned at the knee of a Jehovah's Witness called Ron - a man who he said had a massive influence on his religious outlook.

He was a bright boy - and his parents urged him to go to university. But he also had a problem with authority, unless, as he told his trial, it was his parents or God.

While he was trying to make his way in his studies, he was also developing his political and religious worldview. One of his defining childhood memories was the death of a nephew.

The young boy grieved - and concluded that academic studies might be relevant for mortal life, but "greater success" would be found in entering paradise.

By his late teens Adebolajo concluded that Islam could answer his questions - and he converted during the first year of his politics degree at Greenwich University. All around him there were protests against the devastation of the Iraq war - and Adebolajo shared that anger.

"It was the Iraq war that affected me the most," Adebolajo told the jury in Court Two of the Old Bailey. "I saw Operation Shock and Awe and it disgusted me. The way it was reported was as if it was praiseworthy, saying. 'Look at the might and awe of the West and America.' Every one of those bombs was killing people."

The BBC's June Kelly looks back at how events in Woolwich unfolded

Michael Adebowale, six years Adebolajo's junior, had a troubled upbringing. While the older Michael had entered his teenage years debating the religious and political direction of his life, Adebowale's was already out of control. By the time he was 14 he had become involved in gangs in south-east London.

Steve Adebiyi was one family friend who tried to intervene after an appeal for help from the teenager's mother.

"She brought the boy and I sat him down," said Mr Adebiyi. "I said, 'You are a young man, you have a future, look at the situation... Why are you following these non-entity people?' He was just so quiet... and said, 'Thank you, uncle,' and then he left."

Adebowale's criminal associations were soon to have fatal consequences. By January 2008, Michael Adebowale was now dealing drugs and he was looking after a flat that was being used as a crack den.

Lee James, a professional bare-knuckle fighter and addict, came to buy a hit of crack and then launched a ferocious attack on Adebowale and the two other youths who were with him.

James plunged a kitchen knife into the neck of the first youth in the flat. It was sheer chance it didn't kill or paralyse him.

Adebowale looked on in terror as the second youth, Faridon Alizada, launched at James to defend both of them. The trial judge later said it was a "hopeless mismatch" and Faridon was cut to pieces before Adebowale's eyes.

Finally, James stabbed Adebowale twice before fleeing the scene.

Lee James was jailed for life for Faridon's murder. Adebowale was convicted of drug dealing - and ultimately jailed for eight months in a young offenders institution.

But the attack left more than physical scars. He was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and began suffering periods of acute mental illness, including delusions, such as hearing voices. This mental decline would come to play a key part in his later trial for Lee Rigby's murder.

Adebiyi says that in the aftermath of the stabbing, Adebowale fled Woolwich and wasn't seen for months.

When he later returned to his family in Woolwich, he did so as a Muslim. The police don't know when the Michaels, Adebolajo and Adebowale, first met, but it may have been around this time, given they were both converts in the same part of town.

The older Michael had by now been long kicked off his politics degree and had initially occupied himself by protesting against Western foreign policy alongside al-Muhajiroun.

Back in 2003, the group, now banned under counter-terrorism laws, was led by Omar Bakri Mohammed. He fled the UK in the wake of the 2005 London bombings and is now living in Lebanon.

The group had a considerable presence in Greenwich and the preacher claims that Adebolajo converted after coming to one of his prayer stalls in south London.

Adebolajo's and Bakri's accounts don't quite tally - but there is no doubt that the young man became involved with the organisation. He didn't stand meekly at the back.

In 2006 he joined a solidarity protest at the Old Bailey for Mizanur Rahman, a Muslim man accused of calling for the killing of British soldiers. Things got heated and Adebolajo ended up with a 51-day jail sentence for assaulting a police officer.

The following year, with al-Muhajiroun now rebranded as Muslims Against Crusades, a reference to British soldiers in Islamic countries, the BBC filmed Adebolajo standing behind Anjem Choudary, the group's leader after Bakri fled the UK.

Video has emerged of suspect Michael Adebolajo at an Islamist protest in 2007 (Left, in white clothes)

And in 2009 he was seen again - this time marshalling a protest at a mosque trying to face down a demonstration by the English Defence League.

But then, he says, he went his own way. Adebolajo told his trial that he ideologically split from al-Muhajiroun.

Al-Qaeda-inspired jihadists believe that Muslims cannot be at peace in the West because the West is at war with Muslim lands. The logical endpoint of that thinking is that adherents must either migrate to Islamic lands - or resort to violence because there is no "covenant of security" protecting them and their people.

In October 2010, Adebolajo had had enough of the land of disbelievers and he headed to where he thought he would find a pure form of Sharia rule - Somalia.

There, the militant al-Shabab group had formed an alliance with al-Qaeda and it had the government's forces on the back foot.

The country's porous southern border with Kenya was the entry point for the Westerners al-Shabab was inviting to join them - and Adebolajo followed a path trodden by other Brits.

He headed north from Mombasa on the Indian Ocean coast to a small fishing village close to the border. There, he and four other men waited for facilitators to whisk them across a sea channel to the welcome embrace of al-Shabab.

But it didn't work out. Someone alerted the police - and Adebolajo and the others ended up in court back in Mombasa.

BBC's Gabriel Gatehouse reports from the island of Pate where Adebolajo was detained

When he appeared in the local court, he shouted: "These people are mistreating us and we are innocent, believe me."

The Kenyans deported Adebolajo and he arrived back in London in late November 2010. Although nobody may have noticed his departure, MI5 were now aware that he had come back.

Adebolajo and some of those close to him are thought to have received visits from the security services to find out more about their beliefs and associates.

One of Adebolajo's friends in London, Abu Nusaybah, told the BBC's Newsnight in the days after the attack that MI5 had "harassed" Adebolajo.

The nature of the contact can't be independently verified - including Adebolajo's separate claim in court that MI5 had visited him earlier this year - although it is not uncommon for the Security Service to approach people in an attempt to persuade them to co-operate. Police arrested Abu Nusaybah after he spoke to the BBC - and he now faces unrelated terrorism charges.

But if MI5 weren't able to get Adebolajo to co-operate, could another government scheme have stepped in? Whitehall had poured millions of pounds into an extensive programme of preventing violent extremism and a parallel programme of deradicalisation.

But when some of that funding was pulled after the 2010 general election, one of the groups that lost out was an initiative called Street, based in south London.

Its founder Abdul Haqq Baker told the BBC's Panorama that before Street lost its funding, members of his team had identified Adebolajo as a possible threat.

"Some of my youth workers knew [Adebolajo] and engaged with him," he said. "There were concerns that engagement was needed to enable him to have a better understanding and contextualisation of Islam as we practise it in the UK.

"The traits he was displaying - ideological rhetoric in relation to violent extremism - and the positions that he had adopted, from those he had learnt from before al- Muhajiroun and such entities. Such beliefs needed to be challenged."

Could Street have stopped Adebolajo had it not lost its funding? "I'm confident in our track record that we could have prevented this," he said.

What happened to Adebolajo when he got back to the UK will be a key part of a forthcoming report from the Intelligence and Security Committee, the body that oversees the work of MI5 and MI6. So was Adebolajo on the radar but not under the microscope?

Scotland Yard's head of counter-terrorism, Assistant Commissioner Cressida Dick, said she could not pre-empt that report's findings but would expect it to do its best to answer the nation's questions in as open a way as possible.

"We have thousands of people who have very extreme views, thousands of people under investigation or of concern," she said.

"What I can say is that somebody who comes back from a country like Kenya, in the circumstances that have been described publicly… that is slightly unusual circumstances. You absolutely would generally expect the police to be aware, to be informed, and to wish to speak to that person to see if they have committed any offences… to do a port stop and to assess with others in the agencies what risk that person poses.

"That's what you would expect to happen."

A few miles away from Street's Brixton base, both Michaels were now working the "Dawa" or prayer stalls in Woolwich.

Steve Adebiyi, the Adebowale family friend, said: "The last time I saw him he was handing out flyers. I saw him with one other tall guy. I looked at him and thought I'm not fully convinced that boy is not going to be trouble. But we never knew what trouble it would be."

Another Woolwich woman told the BBC how Adebolajo would stand on Powis Street, Woolwich's shopping High Street, "evangelically hectoring" shoppers coming in and out of WH Smiths.

"I found Michael quite intimidating and thought he seemed dangerous," she said. "Michael was more scary than the others [on the stall] - he had quite an encroaching presence. When I saw the footage of him ranting [after killing Lee Rigby], it was familiar to me from his preaching in Powis Street."

Eight months before Woolwich, Adebowale is now known to have been among more than 200 people who protested outside the US Embassy in London as part of global demonstrations over a film that mocked Islam.

The trial of the two Michaels didn't hear evidence on when and how they landed on the plan to attack a soldier - but it wasn't a novel idea. The UK has seen other al-Qaeda-inspired plots to target soldiers.

Nine days before he killed at Artillery Place, Adebolajo was seen just a mile away at the Glyndon Community Centre.

One prayer-goer, who asked to be known only as Abdullah, told BBC London News that Adebolajo gave an extreme lecture about the conflict in Syria.

"He said that as long as they are disbelievers, we can kill them. It disturbed me," Abdullah said.

Two days before the attack, Michael Adebowale visited his father. The next he would see of his son was on the news.

A day before the attack, Adebolajo bought the knives.

On the day of the murder, he went to fill up his car - but had forgotten money to pay for it. He left his phone with the petrol station as security and later returned with the cash. He later picked up Adebowale and the two were together for almost five hours before the attack. Nobody was following them.

There was only a silent CCTV camera on a shop. It showed a Vauxhall Tigra accelerate and hit Lee Rigby as he crossed Artillery Place, probably on his way to buy a packet of cigarettes.

CCTV records Vauxhall Tigra, moments before it hits Lee Rigby

He was wearing a Help for Heroes top and carrying a military-style kit bag. But he wasn't in uniform and hadn't come from his barracks.

Neither attacker could have known for sure that Lee Rigby was a soldier - but it did not stop them, as Adebolajo explained in a police interview.

Ingrid Loyau-Kennett, who had been on her way to visit her son and daughter, calmly spoke to Michael Adebowale in the aftermath of the murder. He told her not to touch the body.

She said: "I lifted my head and I saw straight ahead at eye level two hands, two bloodied hands, one carrying a meat cleaver, a butcher's knife, and the other one having a revolver. So I thought, right, it's not an accident. We have a situation here.

Witnesses recall aftermath of Lee Rigby killing

"He told me he was a British soldier, and he killed him. So I said, 'Why?' 'Because they drop bombs, the British army purposely drop bombs on civilians in Islamic countries. So it was to avenge all these victims, female and children.'

"I asked him, 'What do you want to do?' That's when he said, 'I want war... here on the streets of London.'"

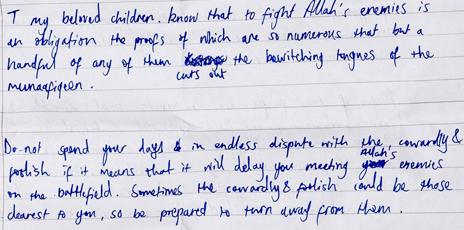

Amanda Donnelly Martin was another eyewitness. Michael Adebolajo gave her a letter - his suicide note.

Adebolajo then delivered his now infamous speech to a mobile phone, waving his bloodstained hands around - a scene that his lawyer told the Old Bailey was "positively Shakespearean", something out of Macbeth.

And then, finally, they waited for armed police to arrive - hoping that Scotland Yard's best marksmen would provide the martyrdom they craved.

But rather than arriving as life-takers, the three CO19 specialist firearms officers were potential life-savers. Within 40 seconds of shooting the two Michaels, they broke out their emergency first aid kit to stem the blood loss from the bullet wounds.

There would be no martyrs that day - but there would be a trial.

Adebolajo and Adebowale entered the dock just six months after the killing.

Both sat quietly, observing the rules of court. They asked to be known by the names Mujahid Abu Hamza and Ismail Ibn Abdullah.

Adebolajo sucked his top lip, having lost his two front teeth in a confrontation with prison officers. The officers have been told they will not face criminal charges over the incident. The Prison Officers Association (POA) has strenuously denied its members did anything wrong.

How could Adebolajo and Adebowale try to avoid conviction for murder given that they were caught at the scene?

Adebolajo wanted to argue that he had a defence to murder under its 17th Century wording - that the crime had to occur "under the Queen's peace". As a soldier at war with the UK, he argued, he was not subject to the monarch's peace - and so Lee Rigby's death was a legitimate battlefield killing.

The judge threw it out, saying that the law didn't allow anyone to simply define when and where they were at war.

Nevertheless, Adebolajo told the jury he was a holy warrior - hence "Mujahid", which he had adopted as his name.

But while the jury heard the older Michael's political and religious philosophy, they heard nothing from Adebowale.

Adebowale suffered a fresh mental breakdown after he was released from hospital into police custody.

"His behaviour was very unpredictable," said Assistant Commissioner Cressida Dick. "He did speak to us, quite a lot, on occasion. But he was also quite violent and his emotional state seemed to go up and down quite a lot.

Met Police Assistant Commissioner Cressida Dick: "His [Adebowale] behaviour was unpredictable"

Adebowale punched one officer, threw water and spat at another. In the end, says AC Dick, he "had to be restrained, very restrained, by specially trained officers".

After his return to hospital, his mental state improved - only for it to decline once more as the trial approached.

He began hallucinating that he could hear voices with a Nigerian accent and was convinced that people were hiding behind doors in Belmarsh Prison, waiting to attack him as he passed.

There were dramatic changes in symptoms and behaviour from one day to the next - and Adebowale even told one of his doctors that he wasn't Muslim, but Christian.

In the end he was judged fit to stand trial but didn't enter the witness box.

Throughout the entire trial his lawyers offered no evidence in his defence, other than to say, in his closing speech, that his client agreed with everything that Michael Adebolajo had said - and he had agreed to join his war.

Lee Rigby's uncle, Ray Dutton praised the community for their support

The two Michaels are now in prison - it's entirely likely that they may never be released.

But the story is not finished. The Intelligence and Security Committee will soon report its findings on whether the men could have been stopped.

That report in the new year may provide some answers for Lee Rigby's family. They sat through the trial, often in tears, but more often than not resolute and dignified.

"This was an appalling, brutal murder of a young innocent man who had no chance to defend himself," said AC Dick.

"I don't think anyone else can begin to understand, I'm sure I can't, what they must have been going through and continue to go through. It was a terrible, terrible act."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external