Bangladesh 1971: Revisiting the scene of my grandfather's murder

- Published

An old conflict is coming back to life in Bangladesh as people accused of taking part in atrocities during the war of independence four decades ago are finally prosecuted. Many want to see justice done - but some say political "show trials" have resulted instead.

"He was killed next door along with three other men. Your grandfather was a very good, honest man, well-known and respected both by the rich and the poor."

These were the words that greeted me and my mother as we arrived at her childhood home in Kushtia, western Bangladesh. She had not seen it for more than 40 years. I'd never been there.

It's a large house. For my mother it's associated with many happy memories - as well as an act of barbarity that cast a shadow over her adult life.

The former family home in Kushtia

My grandfather, Rafiq Ahmed, was a prominent businessman, and it was probably because of his high standing in the community that he was shot by the Pakistani army in April 1971.

Husne Ara Haider on her return to Kushtia

My mother was a student in London at the time of his death and this episode is something she never willingly talks about.

"We heard that his name was probably on a list given to the Pakistan army," she says. "We never received his body. It's very painful not to have anywhere to grieve for him."

There is only one surviving photograph of my grandfather. Everything else was destroyed.

It was in 1971 that East Pakistan broke away from West Pakistan and a new nation was born - Bangladesh.

Accompanying the birth were mass killings, rape and torture, affecting almost every family in East Pakistan.

The strains between West and East Pakistan that finally led to the war, went back to Partition in 1947. The two territories were improbably separated by 1,000 miles (1,500km) of India, and although both were predominantly Muslim, they had little else in common.

When in 1971 a charismatic Bengali leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, organised daily demonstrations demanding independence for East Pakistan, thousands of troops arrived from West Pakistan. On 25 March, they began a military campaign - Operation Searchlight - against what the government referred to as "terrorists" and "Indian agents" intent on breaking up the country.

Professor Sirajul Islam Chowdhury, at the time a young academic at Dhaka University, has vivid memories of what happened.

"This was beyond our imagination comprehension and even fear," he says. "That sort of massacre, it was genocide really that started on that night. Many of my colleagues were killed on that night."

Ten million refugees fled to India. Soon stories of atrocities started to emerge, including the rape of up to 200,000 women.

Ferdousi Piryovarshini was in her early 20s in 1971, living in Kulna, in the south of the country, when her boss sent her to a local Pakistani army commander. He grabbed her by her sari and dragged her into the room, before brutally raping her. She was raped repeatedly by other Pakistani soldiers over a period of eight months.

"My tears have all gone," she says, after years of crying, but being unable to talk about her ordeal.

"My story is told 100 times, 1,000 times by people who are living in the rest of the country. My story is the story of other women in Bangladesh."

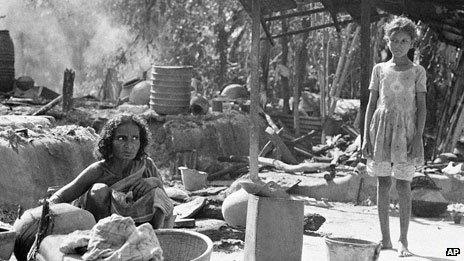

Refugees in Kushtia, April 1971

In December 1971 a full scale war broke out between Pakistan and India.

In the East it was soon over, with 93,000 Pakistani troops becoming prisoners of war. In the new state that emerged, decades of political instability - assassinations, coups and countercoups - made it difficult to hold to account those responsible for war crimes.

Then in 2008 Mujib's daughter, Sheikh Hasina, won a landslide election victory on the promise that she would end the culture of impunity. New elections are due on 5 January.

It's the Bengalis who collaborated with the Pakistani army that are the main focus of popular anger. Many accuse Jamaat-e-Islami, the party of Islam, of setting up paramilitary groups which carried out atrocities.

The first convictions were handed out this year. A number of those found guilty of war crimes have been sentenced to death and one - a Jamaat-e -Islami leader, Abdul Kader Mullah - has been executed.

Activists celebrated after hearing the news of Abdul Kader Mullah's execution in Dhaka

Nearly all the defendants tried so far have been members of the same party, and opposition groups have accused the government of using the trials to hound their political enemies, in the run-up to a general election on 5 January.

Allegations have been made that witnesses changed their statements and that verdicts have been emailed to the government before being announced in court.

One of the most high-profile defendants, 91-year-old Gulam Azam, was given a 90-year prison term in July, for conspiring, planning, inciting and complicity in genocide.

His son, Brigadier General Aman Azmi, says it was not a fair trial, but a "political vendetta".

On the streets of Bangladesh, though, there is a hunger for the trials. Between 80% and 90% of the country is in favour of them, according to Asif Nuzrul, professor of Law at Dhaka university.

But even when there is strong evidence that a defendant was involved in war crimes, it's crucial for society to see that justice is being done fairly - and in his view that is not the case.

"Society is polarised on the question of whether these trials are being conducted fairly, objectively transparently, whether these trials are being conducted for a noble purpose or a political purpose," he says.

There are limits to how far the trials could provide justice for victims even if they were fair, objective and transparent. The vast majority of crimes committed in 1971 - like the murder of my grandfather - were carried out by Pakistani soldiers. None of them are facing prosecution.

Ferdousi Piryovarshini, despite being a victim of crimes carried out by Pakistani soldiers, is angry first and foremost with the Bengali collaborators. She says she is "very happy" that the trials are taking place - but that they will not bring her peace.

Forty-two years after the events of 1971, Bangladesh itself is still not at peace.

To find out more, listen to Farhana Haider's radio report on the Crossing Continents website.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external