Berlin 1914: A city of ambition and self-doubt

- Published

One hundred years ago, Germany was an industrial powerhouse and its capital Berlin had hopes of becoming a great world city. Instead, decades of catastrophe followed.

Let me state the obvious: Berlin today is utterly unlike Berlin on the eve of war a century ago. How could it not be? The disasters which emanated from this city returned and returned again with a punishing vengeance to destroy so much of the bricks and mortar of the past. I think the ghosts are all around but the buildings they might inhabit have often vanished, turned to rubble. Berlin reaped its own whirlwind.

It's true, traces - the outlines - remain, albeit with a strip ripped right through the centre by the Berlin Wall. The Tiergarten is still the park at the heart of Berlin, still delightfully mysterious, uncultivated with dark nooks and glades. The Reichstag has risen again. Somehow the Brandenburg Gate survived. And so, too, the monolithic Protestant cathedral - the Berliner Dom - completed in 1905 on the orders of Kaiser Wilhelm II to rival even the grandeur of St Peter's in Rome. It stands alone, a monument to his ambition, his royal palace across the road now nothing but grass.

So much of Berlin a century ago has gone, destroyed in the wave of catastrophes that followed that first great war. Unter den Linden, the elegant boulevard of a century ago - now just a polluted traffic jam. Potsdamer Platz is a ghastly junction of five roads, negotiated by fearful tourists.

In 1913, it was the social hub of Berlin, where electric trams and people met and gossiped, perhaps taking coffee in the Hotel Esplanade or the Hotel Excelsior, both opened in 1908. At the Excelsior, with 600 rooms, the largest hotel in Europe, you might have glimpsed Charlie Chaplin or the Kaiser who held "gentlemen's evenings" there. The Hotel Piccadilly was there, too, though renamed patriotically as Cafe Vaterland a mere two weeks into the war. Farewell Piccadilly in the ultra-nationalistic Berlin of a century ago.

Berlin Street Scene, 1913, by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

High above the buildings were the new electric advertising hoardings, tracing out the word "SCHOKOLADE" in the night sky. Ladies in grand hats walked arm in arm. Sometimes ladies of wealth, no doubt; sometimes, ladies selling a service. They were painted by the German expressionist painter, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, in his Berlin Street Scenes of 1913. They're glamorous in a way, like strutting birds with big feathers, but also, in his depiction, anxious and furtive and decadent.

A city, then, in flux, a city of contradictions and contrasts and tensions. Berlin on the eve of war was a combination of ambition and self-doubt. The Berlin of today and the Berlin of 100 years ago share one thing - they both were and are "wannabe" cities. Berliners today crave acceptance. They like the idea that their Berlin is becoming a "world city". People come because it's "cool", and Berliners love that recognition.

Berlin before 1914 was also a city looking elsewhere - to London, the great imperial capital, or to Paris with its cultural elan. Berlin was a city craving greater status, to be a "Weltstadt" - a "World City". It had only become the capital of the newly united Germany in 1871, but its population had grown from 835,000 then to two million on the eve of World War One.

The growth had brought ambition. Kaiser Wilhelm II wanted a city which would be "recognised as the most beautiful in the world". For him, this would be a city of monuments and avenues and grand buildings, of fountains and statues, perhaps even of himself. He bemoaned its lack of these accoutrements of the greatest cities. "There is nothing in Berlin that can captivate the foreigner," he said, "except a few museums, castles and soldiers."

Potsdamer Platz

It wasn't true. The statement just showed the Kaiser's limited vision. Actually, Berlin before WW1 was a dynamo of innovation and technological advance. It was doing much to make the modern scientific age, particularly in physics and medicine. Einstein was here, the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics from 1914, alongside a slew of other Nobel prize-winners.

And it wasn't just theoretical advance. In 1896, a wander through the seemingly endless halls of the grand Industrial Exhibition at Treptow Park would have revealed a cavern of modern wonders - from the newest electric motors and engines, to new synthetic dyes, to Bechstein pianos, to literally a sausage machine which could process 4,000 pigs a year.

Unter Den Linden, 1900

The exhibition guide said "Berlin must not only present itself as the largest city in Germany but must give witness to its energy and progressive spirit in all dimensions of its restless productivity." Restless productivity - quite.

An American restlessness. Mark Twain stayed in Berlin and likened it to Chicago in its dizzying growth and thirst for the new and modern. By the turn of the century, Berlin had 10 long-distance railway stations, including the cathedral which was and is Friedrichstrasse. In 1905, a bus line was started, integrating the public transport system - though the Kaiser had his own Daimler, complete with a horn which played the thunder theme from Das Rheingold. Dah-da-dah-de-dah. He needed that horn - in 1913, there were already so many private cars on the streets that policemen had to direct the traffic at junctions.

And people, people, everywhere. Officialdom, perhaps in a very German way, counts things and on 1 October 1900, it recorded 87,266 crossing Potsdamer Platz, the hub of pre-war Berlin. By 1908, the hourly traffic had risen to 174,000. Above all, Berlin before the war was a city of electricity and light - "Elektropolis", Berliners themselves called it. Searchlights picked out the new Zeppelin airship above, and picked out the adverts along its side.

But this wasn't the real marvel of Berlin. For my money, Siemensstadt was the real symbol of the pre-war city. This was, and is, a whole district of Berlin devoted to one company. Siemensstadt means Siemens City, so-called because Siemens, the giant electrical company, occupied the whole district. The red-brick factories are still there, four and five storeys high, running along the straight roads for hundreds of metres. In 1913, a human inventory was done - 7,000 people in one factory, 3,000 toiling in the electric-motor works, 3,000 people in the cable works. This was clearly a city of the future, a city of modernity and power, electric power.

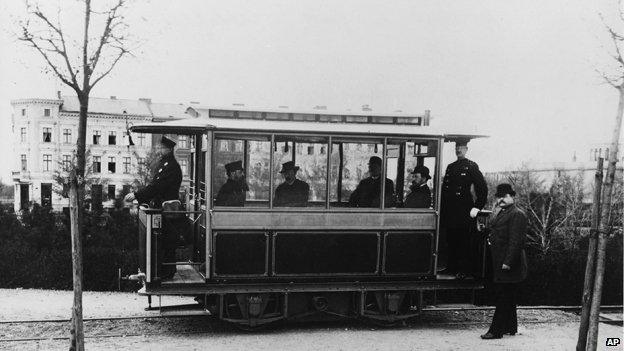

1881: Germany's first electric streetcar, manufactured by Siemens

Industry sucked in immigrants who lived cheek-by-jowl in new blocks which became known as "rental barracks". Fugitives from the poverty of the primitive countryside and the pogroms of the East jostled with those already here.

On the eve of the war, 63% of the four million people in Berlin worked for wages, that is in what you might call modern industry. One questionnaire in 1910 elicited replies from Berliners like: "making mass-produced articles repulses me" and "I feel like a machine".

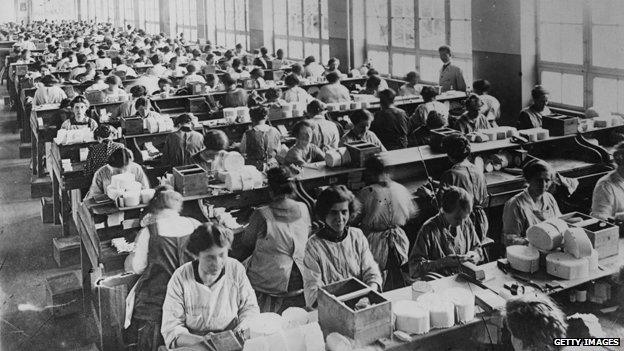

Women were becoming essential to the Berlin economy, in the factories for wages to some extent, but also as seamstresses working at home for a pittance in the proletarian districts on the outskirts. In 1906, the Christian Home Workers' Association drew attention to their conditions with an exhibition. The poster designed by the Berlin artist Kaethe Kollwitz - memorialised today in Kollwitzplatz - depicted a woman with sunken, exhausted eyes. The Kaiser's wife, Empress Augusta, declined to attend. The poster was too depressing, she said. Industrial Berlin was a place of deep class tensions.

Workers in a Berlin factory, 1913

And gender tensions. One newspaper article of the time, entitled The Effect of Sewing Machine Work on the Female Genital Organs, concluded that long hours hunched over the Singer sewing machine could result in women not being able to conceive children.

Others (invariably male) worried about women who increasingly worked in factories near men who were not their husbands. Where might this lead? An august committee of the Reichstag opined that a woman's proper place was "at the cradle of her child". Not that it mattered. The vibrant, pre-war economy needed hands and hands were what it got, male and female.

Writing in 1910, the sociologist Max Weber described the city and captured the tensions and the excitement of what he called its "wild dance of impressions of sound and colour". There were tramways, underground railways, electric lights, display windows, concert halls and cafes, smokestacks, masses of stone.

And above this city of strife and contrast and flux was the Kaiser, unsympathetic, to say the least, to any proletarian ambitions except those involving the wearing of uniforms and aggrandisement of Germany, at the time barely 40 years old as a nation. When tram-workers went on strike in 1910, the troops were called out and Kaiser said he hoped that "five hundred of the strikers might be gunned down".

It wasn't only economic grievances that brought workers out on strike. They struck, too, to widen the franchise. Again, the Kaiser was resistant. The Left was strong in Berlin. In the Reichstag elections of 1912, 75% of Berlin's votes went to the socialists - but the Kaiser wished them away, calling the Social Democrats a passing phase. He was wrong.

What he offered instead was national, imperial ambition and jingoism. He was a man of the grand statement and, occasionally, the grand gesture, sometimes with laughable effect. When Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show visited Berlin, one of the acts involved Annie Oakley asking a volunteer from the audience to smoke a cigar while she retreated the 40 paces to shoot the tip off with her Colt 45. Actually, it was her husband - but nobody knew that. But this time, the Kaiser jumped forward and - so the story went - drew a cigar from his golden case and lit up. Annie, unable to back out, dutifully fired the shot and hit the cigar but missed the royal head. The story varies with each retelling, but Annie is said to have written to the Kaiser during the war and asked if she could take a second shot.

The Kaiser imagined that war would unite his loyal subjects. On the very eve of war - the morning of 4 August 1914 - he announced that from that moment he recognised no political divisions, no political parties. "From this day on, I recognise only Germans," he said.

It is true that the citizenry (or many of them) were ecstatic. Bands played patriotic tunes ceaselessly in the cafes. The actress Tilla Durieux wrote breathlessly, "Every face looks happy. We've got war! One's food gets cold, one's beer gets warm. No matter - we've got war!" The Association of German Jews proclaimed that every German Jew was "ready to sacrifice all the property and blood demanded by duty".

That was the atmosphere on the eve of war, exactly 100 years ago. Berlin, this city, seemed like the ebullient capital of a confident nation growing into an imperial power. It was a false impression. Behind that facade were divisions that would crack very quickly.

On 9 November 1911, August Bebel, the Marxist politician who was one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party, rose in the Reichstag and made this speech, warning about the route down which Germany was hurtling: "There will be a catastrophe. Sixteen to 18 million men, the flower of different nations, will march against each other, equipped with lethal weapons.

"I am convinced," he went on, "that this great march will be followed by the great collapse."

At which point, laughter broke out in the chamber. Bebel picked up: "All right, you have laughed about it, but it will come. What will be the result? After this war, we will have mass bankruptcy, mass misery, mass unemployment and great famine."

Some - a few - saw it. The tragedy is that they weren't the masses in this city nor those who ruled them.

Music on the Brink: The Essay series will be broadcast Monday to Friday this week at 22:45 GMT on BBC Radio 3. Monday: Vienna Tuesday: Paris. Thursday: St Petersburg. Friday: London.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

Find out more on the BBC World War One website