Douglas Mawson: An Australian hero's story of survival

- Published

Mawson's ship, the Aurora

One hundred years ago this week, Australia's foremost polar explorer, Douglas Mawson, returned home after two years of triumph and terror in East Antarctica.

At the end of February 1914, Douglas Mawson sailed into the port of Adelaide to a hero's welcome. His final sentence in The Home of the Blizzard, his own account of his adventures, conveys a feeling of overwhelming emotion at his reception: "The voices of innumerable strangers - the handgrips of many friends - It chokes one…"

The intensity of feeling may have been coloured by regret and guilt, welling from memories of the deaths of his two friends and his own near demise, on a disastrous trekking expedition one year earlier.

Douglas Mawson is one of the less celebrated figures of the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration. Yet his story is as gripping as the exploits of Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen, even though he didn't seek the glory of being the first to reach the Geographic South Pole.

His Australasian Antarctic Expedition arrived at the frozen continent towards the end of 1911, when Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen were racing to the planet's most southerly point.

Scott had in fact asked Mawson to join his ill-fated Terra Nova expedition. The Australian had won his Antarctic spurs as a geologist with Scott's rival, Ernest Shackleton, between 1908 and 1909. Mawson was in the three-man party which was the first to reach the Earth's Magnetic South Pole (although some suggest they did not quite make it to the exact spot). Mawson impressed both British expedition leaders.

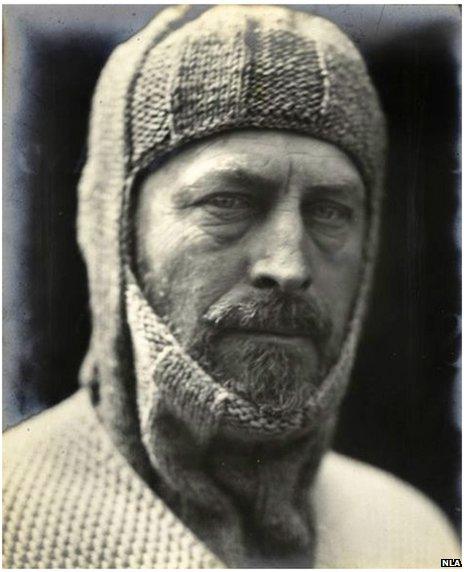

Douglas Mawson on a later trip, about 1930

The young geologist declined the place in Scott's team. Not even out of his twenties, Mawson had decided he wanted to lead an expedition of his own, dedicated to scientific discovery and exploration.

His plan was to explore a tract of Antarctic coast and its hinterland which lay south of Australia, on the far side of the fearsome Southern Ocean. To get there, Mawson had first to launch a fundraising crusade.

Antarctic historians often note Douglas Mawson's drive and determination. That no doubt helped him to amass the equivalent today of about £10m ($16.7m) in little more than one year. Part of the money came from the Australian and British governments. Mawson also tapped businessmen with interests in mining and whaling. The exploration of Antarctica was never, and will never be, unsullied by commercial and geopolitical concerns.

Part of the coastline Mawson explored had been scouted in 1840 by the French explorer Dumont D'Urville. But no-one had set foot there before Mawson's expedition.

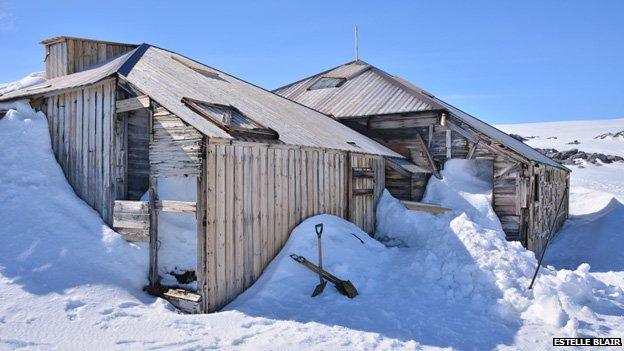

Landing was difficult because most of the coast was formed of high ice cliffs. Only after many weeks did the expedition come to Commonwealth Bay and spot a small rocky section of shoreline with a natural harbour. Mawson established his wood-built headquarters here and named the site Cape Denison.

Conditions at the expedition's base were cramped and basic

The meteorological station recorded an annual average wind speed of 80km/h. This made work and life in general for the men of the expedition extremely uncomfortable and dangerous, particularly during the winter.

Mawson described a typical foray outside the hut in a mid-winter blizzard: "A plunge into the writhing storm-whirl stamps upon the senses an indelible and awful impression seldom equalled in the whole gamut of natural experience. The world a void: grisly, fierce and appalling. We stumble and struggle through the Stygian gloom; the merciless blast - an incubus of vengeance - stabs, buffets and freezes; the stinging drift blinds and chokes."

Mawson and six others were detained here, in what the Guinness Book of Records describes as the windiest place on earth, for a whole year longer than planned.

This was the consequence of a series of disasters during a trekking expedition which set off from Cape Denison on 10 November 1912.

The 32-year-old Mawson left with two younger companions - Xavier Mertz, a Swiss mountaineer and ski champion, and Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis, a 23-year-old British army officer. With 12 dogs and two sledges, the party headed to the far east of Cape Denison.

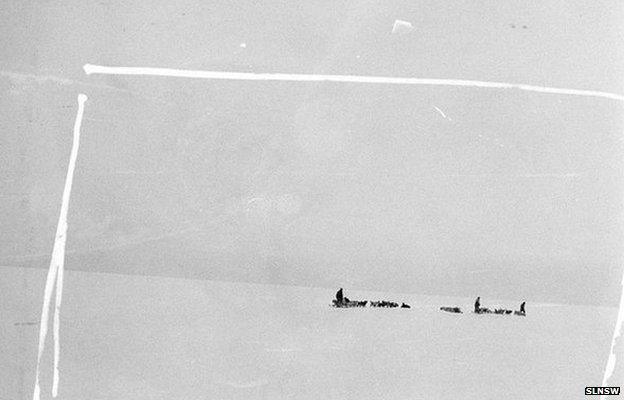

Dogs pull a sled ridden by Xavier Mertz

The last photograph of Mawson, Mertz and Ninnis together

The aim was to explore and map the coastal hinterland - if possible, as far as the neighbouring sector where Scott's expedition had been. Battling through frequent blizzards and crossing two large and dangerous glaciers (subsequently named Mertz and Ninnis), the three men reached a point more than 500km from their base at Cape Denison.

Xavier Mertz clears snow at base camp

Mawson's diary reveals that their initially high spirits - particularly those of Ninnis - began to slump after several weeks of intense exertion and hardship on the East Antarctica plateau.

Then a series of catastrophes ensued, beginning on 14 December.

As the team crossed an ice field, riven with crevasses concealed by snow, Ninnis and the six strongest dogs fell to their deaths into a chasm hundreds of feet deep. Most of the human food, all of the dog food and the main tent went with them.

The accident left Mawson and Mertz with 10 days' food supply for a journey back to base that would take at least a month.

As they retreated, Mawson severely rationed the remaining food. They also started to kill the dogs- eating the "best" bits themselves and feeding the rest to the remaining dogs.

The best bits included the liver. But unbeknown to them, this apparently nutritious addition to their meagre diet in fact put them in greater peril. Both of them began to sicken.

On 30 December, Mawson wrote: "Xavier off colour. We did 15 miles, halting at about 9 am. He turned in - all his things very wet. The continuous drift does not give one a chance to dry a thing, and our gear is deplorable. Tent has dripped terribly, all caked with ice."

As the days passed, their skin started to fall off. They suffered terrible stomach pains and diarrhoea - symptoms of an excess intake of vitamin A. Dog livers contain high levels of the nutrient and too much of it is toxic to the human body. For some reason, Mertz suffered the worst and the one-time Olympic skier was soon reduced to a demented sliver of his former self.

Mertz's suffering reached its climax on 7 January. Mawson described the event in his journal: "During the afternoon he has several fits and is delirious, fills his trousers again and I clean out for him. He is very weak, becomes more and more delirious, rarely being able to speak coherently. At 8 pm he raves and breaks a tent pole. I hold him down, then he becomes more peaceful and I put him quietly in the bag. He dies peacefully at about 2 am on the morning of the 8th. He had lost all the skin of his legs and private parts. I am in same condition and sore on finger won't heal."

Mawson had another 160km to slog across to reach the safety of his base on the coast. And he had a deadline - 15 January. That was the date by which all the sledging parties had to return for the imminent departure of the expedition's ship, the Aurora, for Australia. The ship would not be able to return for at least eight months, after the next Antarctic winter.

An unidentified expedition member with an "ice mask"

But if it had seemed his situation could not get any worse, he then fell into a crevasse himself. His sledge caught on the edge of the opening and he was left dangling on a harness. One attempt to haul himself out failed just as he reached the crevasse lip, and he fell metres deeper into the abyss.

In The Home of the Blizzard, Mawson wrote: "Below was a black chasm. Exhausted, weak and chilled (for my hands were bare and pounds of snow had got inside my clothing) I hung with the firm conviction that all was over except the passing. It would be but the work of a moment to slip from the harness, then all the pain and toil would be over."

An exhausted-looking Douglas Mawson on his return from the ill-fated far east sledging trip

Somehow he managed to summon the strength from his starved body for another bid to pull himself up and out.

And this was only the first of several crevasses into which he fell.

The psychological trauma of Mawson's ordeals after the death of Mertz cannot be under-estimated, says Mark Pharoah, curator of the Mawson Collection at the South Australia Museum in Adelaide.

"He had to erect the tent each evening by himself, which could be very hard in a blizzard. [He had to] navigate and just try to keep a handle on his own anxieties about missing the boat, about the next crevasse. It was a very disturbing time in Mawson's life."

His one eventual stroke of luck was to come across a stash of food and a note left by a search party. The message had been left the previous day and told Mawson that he was now only about 40km from the base at Cape. But slowed down by raging blizzards and his ravaged physical state, he reached the final approach to the base only to see his ship, the Aurora, far out to sea on 8 February.

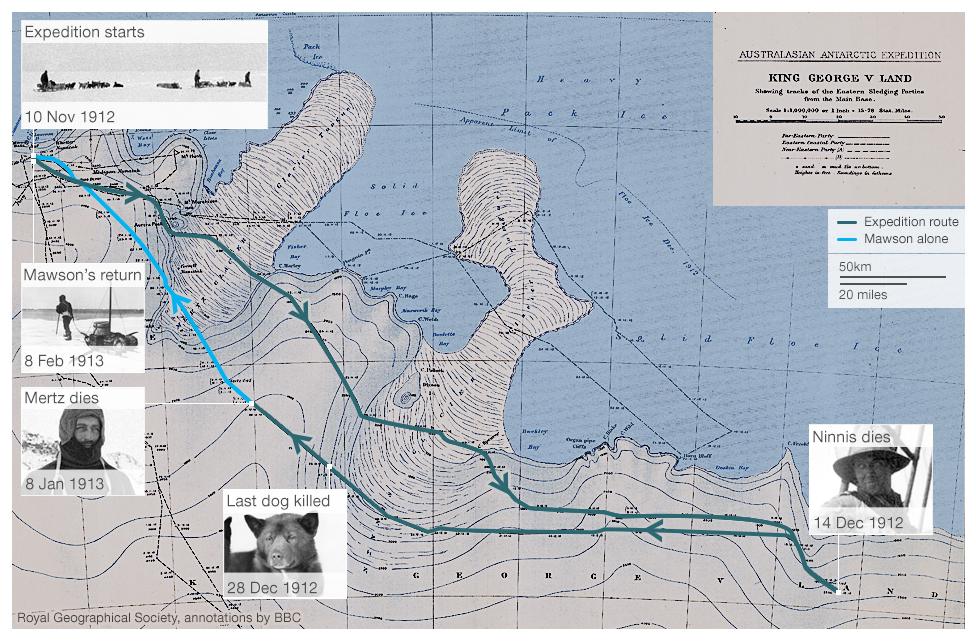

The route of the far-eastern sledging party

10 Nov 1912: Mawson, Ninnis and Mertz set off on their expedition to map the far east of King George V Land.

14 Dec: Ninnis, the six best dogs, almost all of the food and the bulk of their most important equipment - including their tent - are lost down a crevasse 11ft wide and 150ft deep. Mawson and Mertz decide to return to the hut as directly as possible.

15 Dec: Mertz and Mawson eat dog meat for the first time.

28 Dec: Their last remaining dog, Ginger, collapses and is killed. The men will now have to get back under their own steam.

8 Jan 1913: At 2am, Mawson wakes to find Mertz has died. "Now so weak and starved there seemed little chance of my getting back," Mawson writes.

8 Feb: Approaching the base, Mawson sees a ship's smoke on the horizon. This was Aurora leaving. It would not be able to return for another 12 months.

Source: Australian Antarctic Expedition 1911-14. Scientific reports, Series A Vol 1. Part 1 by Douglas Mawson.

He was not alone though. A party of six men were waiting for him at the base. Using the wireless telegraph, they tried to recall the ship but the weather was so bad it could not return to shore. Mawson had to remain for another year and endure a second ferocious winter in the land of the blizzard.

On 23 March, he wrote: "I find my nerves in a very serious state, and from the feeling I have in the base of my head I have suspicion that I may go off my rocker very soon. My nerves have evidently had a very great shock."

Despite his ordeal, the additional year helped to ensure that the Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a scientific and technical success. Another winter gave them the opportunity to better study the electro-atmospheric phenomenon of the Aurora Australis, the Southern Lights. When the summer came, the remaining team were able to map the further reaches of this new part of the British empire, and survey and sample its wildlife and geology. Mawson's team discovered the first meteorites in Antarctica.

The second year also gave them the time to make the wireless equipment they had brought with them in 1911 work at long range. Mawson's expedition was the first to connect Antarctica to the outside world by radio.

On his return, Douglas Mawson took his place as a great figure in the Heroic Age of Antarctica Exploration. In 1984, 70 years on, his face appeared on the 100 Australian dollar bank note. His stock as a great explorer remained high as the reputation of Robert Falcon Scott as an expeditionary leader fell.

Mawson (standing, centre) and colleagues on board the Aurora

However, the subsequent publication of Mawson's Antarctic journals and access to the diaries of other Australasian Antarctic Expedition members have made some historians revise the glowing assessments of his exploratory and leadership qualities.

Even in the early days, some had questioned the way Mawson had commanded the disastrous far eastern sledging trek. Was it a sensible decision to put so much of their vital provisions on one sledge - the one which then disappeared with Ninnis into the crevasse?

The newer information has led to further criticism. A century after Mawson's return from the land of the blizzard, Mark Pharoah says the view now is of "a Mawson who wasn't so capable of navigating, a Mawson who took great risks at times in his drive to go the farthest of all the sledging parties, and a Mawson who, in the second year particularly, struggles to keep any leadership of the volunteer party which has stayed behind. And one has to wonder how he lived with the responsibility of two men dying under his command."

In December last year, I arrived in Commonwealth Bay with members of an expeditionary team aiming to follow in Mawson's footsteps. In most ways, our experience was entirely different.

For one thing, barely a breeze blew for almost a week. It was only on the intended final day close to the East Antarctic shore that we received a true taste of the land of the blizzard. Fierce winds began to blow from the south-east, mobilising a break-out of thousands of square kilometres of thick sea ice. Logistical cock-ups delayed our vessel's retreat from the area. Enquiries are now under way to establish whether they contributed to us becoming surrounded and trapped by the ice.

We were then periodically lashed by blizzards for 10 days. On 2 January we were rescued, thanks to the combined efforts of a Australian ice-breaker and a helicopter team from a Chinese ice-breaker, which itself became trapped trying to reach us. In total we were stuck in Antarctica for about two-and-a-half weeks longer than we had bargained. It was a minor delay - a faint echo of what happened to Mawson and his six companions.

Mawson's hut at Cape Denison as it looks today.

The interior is well preserved...

...even down to the condiments.

And here is how it looked, decorated for a mid-winter party more than 100 years ago

Picture of Douglas Mawson in 1930 from National Library of Australia - Catalogue number vn4925816.

All other archive pictures courtesy of State Library of New South Wales

Listen to Part One and Part Two of The Return to Mawson's Antarctica on the BBC World Service website. Find more episodes or download the podcasts of the Discovery programme here.