Gulnara Karimova: How do you solve a problem like Googoosha?

- Published

A year ago, the daughter of the Uzbek president was riding high - a businesswoman, a pop star with a catchy name, she was even seen as a possible future leader. But over the past 12 months all that's changed - her businesses closed, her official positions snatched away. Can she bounce back?

The night Tahir tried to kill himself he dreamed about his mother.

He woke up with her voice still ringing in his ears and felt a familiar, suffocating panic. For a long time he lay in bed, torn by a desperate desire to see her and the all-encompassing fear of being sent back to Uzbekistan. Then he got up, and careful not to wake others, shuffled out of the room and into the garage.

By the time one of Tahir's flatmates peeked through the door, Tahir had a rope around his neck.

"I am tired," Tahir says, explaining his failed suicide attempt. His hands are shaky, there is a nervous twitch to his left eye and he has a visible physical deformity, a result of torture he says. He asks me not to describe it. "They'll know who I am," he says. "They'll find me."

Tahir is not his real name and he doesn't want to reveal where in Scandinavia he is, as he waits for asylum. He says the Uzbek security services photographed every scar and birthmark on his body, and even made him walk on camera. "No-one knows me like they do. I am 100% identifiable," he says.

Tahir's story is a tale of extortion and blackmail, which started when Uzbek customs officials and later police, tried to take over a successful business he was associated with. Tahir's partners suffered too. Tahir went to jail where he says he was tortured and saw inmates killed by guards. Eventually he bribed his way out of prison and fled Uzbekistan.

Tahir's asylum lawyers say they have traced his troubles all the way up to Uzbekistan's most famous public personality - Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of President Islam Karimov.

Tahir's is one of many stories that won Karimova the reputation of being a "robber baron" - that's how US diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks described her.

But for many outsiders, Gulnara Karimova is the friendly, modern face of one of the most repressive regimes on earth. The Harvard-educated 41-year-old has been a businesswoman, a fashion guru, a diplomat, a philanthropist - and a pop star, Googoosha, external. In recent months, she has also acquired a new image: that of a defender of human rights.

Googoosha in the video for her single Round Run

As Karimova's business and media empires have crumbled, she has become an outspoken critic of Uzbekistan's repressive government.

"Another re-branding exercise," says a former adviser to Karimova, who asked not to be identified due to fear of retribution. "I don't believe for a second that she has changed. It's all part of her battle for survival."

The battle is a family feud worthy of Shakespeare, but it is unfolding - in part at least - on Twitter.

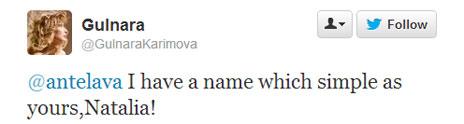

I have been exchanging tweets with Karimova, on and off, for more than a year.

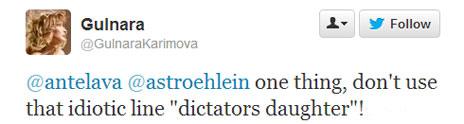

"Don't use that idiotic line 'dictator's daughter'," she told me and Andrew Stroehlein of Human Rights Watch, in one of her first tweets - adding that she would prefer to be referred to by name.

Her messages, whether in Russian or broken English (odd for someone who likes to boast of a Harvard degree), are often elusive and full of riddles. But her Twitter feed has still projected a shaft of light on to the bizarre world of Uzbek politics. Over the last few months, she has moved from sharing pictures of herself at fashion shows and in various yoga poses to accusing her mother and sister of witchcraft, and her father's officials of repression and abuses.

The main source of Karimova's troubles is a European corruption case. In 2012, a group of Swedish journalists investigated Finnish-Swedish Telecommunications giant TeliaSonera and discovered that the company paid $300m as a fee to enter Uzbekistan's lucrative mobile phone market. The money went to a small company registered in Gibraltar in the name of Gayane Avakyan, a woman with no apparent connection to the telecoms world.

Sources close to Karimova say Avakyan, who is in her early 20s, was a shop attendant in one of the many boutique stores Karimova owns in Tashkent and was recruited to help out at one of Karimova's fashion shows in Moscow. She quickly became one of her most trusted assistants and in 2013 found herself in the midst of one of Sweden's biggest-ever corruption scandals.

Karimova's dynamism contrasts with the oppressive regime run by her father

Prosecutor Gunnar Stetler, who is in charge of the case, says he has no doubt that officials from TeliaSonera bribed officials in Uzbekistan in order to enter the Uzbek market. The investigation is complex, he says, and involves 10 European countries. In Sweden, the telecom company's CEO and a number of board members have quit and four senior managers were recently forced to resign for what the company described as behaviour that was not "in line with sound business practices".

One of the journalists who investigated the TeliaSonera case, Joachim Dyfvermark, says no-one seems to know how much Karimova is worth but adds "from what we have seen the $300m from the TeliaSonera deal could be just the tip of the iceberg". It has been reported that she has a portfolio of 17 expensive properties around the world - though Karimova says she owns only one house in Geneva, and one flat in France, in addition to her home in Uzbekistan.

In our Twitter conversation, Karimova denied any connection to the TeliaSonera case. But this is not the only problem she has faced. In a separate corruption investigation in Switzerland, bank accounts linked to her have been frozen. Police have searched her properties in Geneva and France.

For five years, she is believed to have controlled Uzbekistan's largest conglomerate, a Swiss-registered company called Zeromax. She has always denied any connection to the company which published profits of $3-4bn a year until it was mysteriously shut down in 2010.

Kamollodin Rabbimov, a political analyst who used to work for the presidential administration but is now based in France, says Zeromax was causing such problems that Islam Karimov decided to close it.

"Gulnara monopolised entire sectors of the economy," he says. "She started interfering in sales of natural gas, gold trade, logistics. She was sucking away so many resources that she single-handedly created a budget deficit."

After Zeromax, Karimova became ambassador to Spain and representative of Uzbekistan to the United Nations in Geneva. She started spending more time in Europe and worked hard on her image as singing star Googoosha. Sting, Julio Iglesias and the French actor Gerard Depardieu all became her personal guests in Tashkent.

"It was like she owned the country," remembers John Colombo, a Los Angeles-based producer who flew to Uzbekistan to produce one of her music videos, called Round Run. At the airport, he recalls, he picked up a newspaper which featured her on the cover. As they drove into the city, Googoosha's songs played on the radio, her face looked down from a giant billboard. They drove past several music shops she owned. "She was everywhere," he says.

Colombo liked Karimova. He said that at six feet tall she had a striking and powerful presence, but she was also down-to-earth, willing to work hard, and "people seemed to love her".

Even though diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks once described Karimova as the "most hated person" in Uzbekistan, on trips to the country I have met plenty of people who liked her. The contrast between the young, dynamic woman and the oppressive security regime run by her father worked in her favour.

Steve McNulty, the director for the British Council in Tashkent, says his organisation partnered with the youth wing of Karimova's charity, Fund Forum, because it gave them unprecedented access to young people in Uzbekistan. He refused to comment on whether the British Council had any reservations about working with Karimova.

In 2012 Karimova's influence was at its height. As many mentioned her as a possible successor to her father, she too started hinting at her presidential ambitions.

No-one could have foreseen the abrupt and dramatic reversal of fortune she was about to suffer.

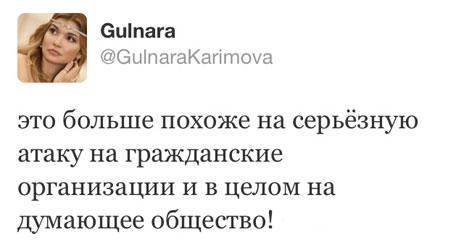

By late 2013, Karimova's business empire had unravelled. One by one her charity, her TV stations, her stores were all shut down. But if Zeromax's disappearance a few years earlier had been enigmatic, this time the drama unfolded live on Twitter. Uzbekistan-watchers followed in awe as Karimova waged war on her own family.

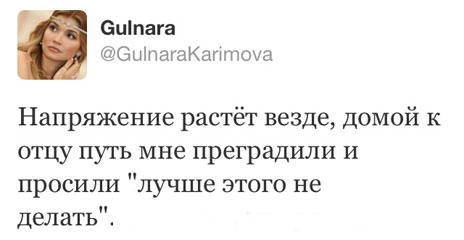

"This looks like a serious attack on civic organisations, and on thinking society as a whole," she tweeted at the end of November, when her charity, Fund Forum, was shut down. "Tension is growing," she added in her next tweet.

11:43 30 November 2013: Tension is growing everywhere, going home to my father my path was blocked and they told me "it's better not to"

In September 2013, in an exclusive interview with the BBC's Uzbek Service, Karimov's youngest daughter expressed scepticism about her sister's chances of gaining the presidency and confided that the two were not on speaking terms. Gulnara Karimova took the interview as an invitation for a public fight.

Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva: No contact with sister for 12 years

She accused Lola and their mother Tatiana Karimova of using black magic to plot against her, and blocking access to her father. But her main enemy and the mastermind of her troubles, she announced on Twitter, was her father's top security man Rustam Innoyatov.

An internet search returns only one or two faded photographs of Innoyatov, a career KGB officer and one of Karimov's most trusted advisers. Since 1991, he has been in charge of Uzbekistan's most powerful institution, the SNB - the successor of the Soviet-era KGB.

In recent months, Karimova appears to have gained an unexpected insight into the role that the SNB plays in the lives of millions of Uzbeks. She has been tweeting about arrests in the middle of the night, fear, attempts to crush any sign of dissent. As many of her employees have been detained or reported missing, she has vowed to defend them.

"I understood a lot, I saw a lot with my own eyes. It's painful but we have to accept the truth," she wrote to me.

Tahir, the businessman from Uzbekistan laughs at the idea of Karimova as a human rights campaigner.

"It's just a game. The rich and powerful are playing their game, but what is going to change for us? I don't think Gulnara is in real trouble. It's just a game between the father and daughter to fool us, the people," he says.

If it is a game, it's a big one. The stability of the whole of Central Asia depends on Uzbekistan - the region's largest country. And that's why it is important to establish who is behind Gulnara's troubles.

It could be that President Karimov himself has ordered her wings to be clipped - or it could be, as she claims, Rustam Innoyatov, in which case this amounts to a palace coup against Karimov's leadership.

Kamollodin Rabimmov does not believe Innoyatov has acted on his own. He says the president was furious when he heard about the TeliaSonera scandal - it led to a number of other revelations about his daughter's excesses and he asked Innoyatov to curb her power. But the question is, can Karimov punish his daughter without weakening himself?

The answer, according to Rabimmov, is No. Karimov has always been merciless towards his opponents - all Uzbek opposition leaders are either in jail, in exile or dead. But a disobedient daughter poses an entirely new challenge.

"Gulnara knows that she won't be jailed and she won't be killed. So the question is: how do they shut her up? Turn off her wifi? That's not a serious solution," says Rabimmov.

He adds: "They can't let her leave Uzbekistan. That's unacceptable to Karimov, because she has shown that she can speak against him."

She may have lost a lot of power, but with all her money, with her father still in charge, and with everything she knows, it is too early to write Karimova off.

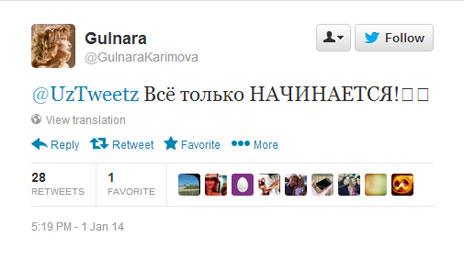

"This is just the beginning," she tweeted in reply to one of her supporters on New Year's Eve.

What happens next depends on her father. For over two decades Islam Karimov has ruled Uzbekistan with an iron fist. But can the Uzbek King Lear control his unruly daughter?

Listen to Searching for Googoosha by Natalia Antelava on BBC Radio 4's Crossing Continents, external at 11:00 on Thursday, or catch up later on the iPlayer

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external