Uzbekistan's Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva reveals rift in first family

- Published

Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva, the second daughter of Uzbekistan's president

They are the glamorous daughters of Uzbekistan's authoritarian President Islam Karimov, mixing with international celebrities and enjoying a jet-set lifestyle.

But now, in comments given exclusively to BBC Uzbek, the younger sister, Lola Karimova-Tillyaeva has revealed an extraordinary rift at the heart of one of Central Asia's most prominent ruling families.

"My sister and I have not spoken to each other for 12 years," Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva says.

"There are no family or friendly relations between us."

Ms Karimova-Tillayeva's frank comments about the complete breakdown of her relationship with her sister, Gulnara, are a rare crack in the secrecy and media silence that usually surrounds Central Asia's all-powerful political dynasties.

They are also highly unusual in a culture where family bonds are hugely important.

Their father, Islam Karimov, has ruled Uzbekistan with an iron fist for more than 20 years. He is accused of presiding over a country where no dissent is tolerated and where torture is rife in prisons.

While the ruling elite enjoys wealth and privilege, hundreds of thousands of ordinary Uzbeks work as migrant labourers abroad because they can't earn a living at home.

Mr Karimov's elder daughter Gulnara regularly makes headlines, having forged a public persona as a pop star, diplomat, fashion designer and philanthropist. She is also an influential businesswoman and tipped as a possible successor to her 75-year-old father.

Her younger sister, Lola, currently serves as Uzbekistan's ambassador to the UN cultural organisation, Unesco, and lives in Geneva.

Lola is notorious for having unsuccessfully sued a French online journal after being labelled a "dictator's daughter",

Despite the parallels in their lives and career paths, the two sisters apparently have little in common.

"Any good relationship requires a similarity of outlook or likeness of character," says Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva.

"There is nothing like that in our relationship, has never been and is not now. We are completely different people. And these differences, as you know, only grow over the years."

'We don't talk politics'

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva answered a series of 18 questions put to her by BBC Uzbek via e-mail.

Gulnara Karimova, the first daughter of the Uzbek president

Distancing herself so openly from her sister may suit Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva at a time when Gulnara Karimova has been linked to a wide-ranging fraud probe in Europe.

Prosecutors in Sweden and Switzerland are investigating current and former associates of Gulnara Karimova on suspicion of bribery and money-laundering.

Some of Ms Karimova's properties in France and Switzerland have reportedly been searched.

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva remains tight-lipped about the investigations and says she does not know whether her father is aware of what is going on.

"All the information about my sister, I get from the foreign media, including the BBC website," she says.

"Regarding your question whether the Uzbek president is aware, I don't have such information. I am only two to three times a year in Uzbekistan. During the meetings with my father, we don't discuss political issues."

President Islam Karimov has ruled Uzbekistan for over 20 years

Because of his age, there is continuous debate about President Karimov's eventual successor.

In the clan and family politics of Central Asia, presidential offspring are often considered contenders. But Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva says she is not interested and that her priority is her husband Timur Tillyaev and their three children.

"The question often seems relevant in respect of members of presidential families in the former Soviet Union," she says. "For now I cannot see myself developing as a politician."

Gulnara, by contrast, has been highly visible in Uzbekistan. Her "Fund Forum" foundation is active in many parts of public life, from promoting Uzbek arts and culture to health and social campaigns.

She has also hinted that a presidential bid may not be out of the question.

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva dismisses her sister's chances outright.

"I would assess these odds as low," she says in a brief comment.

Even though Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva's remarks to BBC Uzbek have been widely reported in regional media, her sister has so far not responded and routinely refrains from responding to BBC requests for comment.

What she makes of her younger sister's extraordinary revelations is anyone's guess.

Competing charities

The Karimov daughters seem to go head-to-head in almost all spheres of life.

Both run their own separate charity organisations.

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva talks in detail about her "You are not alone" foundation in support of orphaned and disabled children in Uzbekistan, work which she describes as "her calling".

But even on this topic she appears to criticise her publicity-savvy sister who regularly tweets about her own charity work.

"I have noticed that the more you talk about what you're doing, the less pleasure you get from your business," she says.

It seems that Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva is not just distancing herself from her sister, but from the image of her country which is regularly portrayed as one of the worst dictatorships by human rights organisations.

In 2011 she took legal action in France against the news website Rue 89 over an article which described her as a "dictator's daughter".

The article also claimed she tried to whitewash her country's image by paying big sums to celebrities like the Italian actress Monica Bellucci to appear at charity events.

The case was thrown out.

At the time most media interpreted her action as a defence of her father's record. But in her comments to the BBC, Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva appears lukewarm in support of her family.

"I did not question the rightness or wrongness of using this word, because I understand that this is a political term," she says.

"However, in that context, the definition of 'dictator's daughter' in the press uniquely affected my personality. Each person is born with the inalienable right to be judged on his personal qualities, business, attitudes and actions."

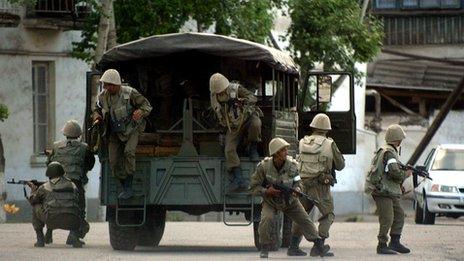

Uzbek soldiers are seen here on patrol in Andijan, where they were accused of killing hundreds of protesters in 2005

She also appears to hold some critical views of her father's government's policies.

Uzbekistan has been criticised for years over the use of child labour during the annual cotton harvest.

"I find it difficult to assess the situation, but if there are such facts, it is sad and should not take place in any country of the world," she says.

"I categorically reject any use of force, whether it is forced labour or other forms of violence against any person, especially children."

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva is also forthright when asked about accusations that her father suppresses any dissent under the pretext of fighting Islamic extremism

"The problem of radicalisation is more a result of unemployment and a lack of opportunities," she says. "These two factors are the most important sources of discontent among the population and in turn inextricably linked to the problem of extremism."

More remarkably still, she says she believes that using force to deal with these problems is wrong.

Her words are in stark contrast to her father's beliefs.

President Karimov made headlines in June when he launched an unprecedented attack on the county's migrant work force, calling Uzbeks seeking jobs abroad "lazy people" who were a disgrace to the nation.

"One feels disgusted with the fact that Uzbeks have to travel there for a piece of bread. Nobody is starving to death in Uzbekistan," Mr Karimov said.

Home comforts

But despite Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva's apparent attempt to distance herself from her family, there has been much media interest in her own significant wealth.

In 2010 she and her husband Timur bought a mansion in the exclusive Vandoeuvres area of Geneva, reportedly for $46m (£29m).

The Karimova-Tillyaeva family at home in Geneva

The couple were also named in a list of Switzerland's richest people by the business magazine Bilan.

Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva is evidently aware of the sensitivity of such reports, given the economic difficulties suffered by most Uzbeks at home.

"We ourselves were surprised when we saw we were ranked among the richest people in Switzerland. I still joke about it with my husband," she says, adding that the figures suggested by the press were "far from reality".

Asked to explain their wealth, Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva says that her husband has a share in a trade and transport company.

In a carefully worded statement, she says that Mr Tillyaev has never been involved in public tenders, been associated with national resource industries like gas or cotton, and does not enjoy tax exemptions or monopoly status.

She also says that they have not benefitted from her family connections.

Reports say that Timur Tillyaev runs the Abusaxiy transport and import company, a profitable market leader in Uzbekistan.

As for their luxury home, Ms Karimova-Tillyaeva says that the couple took out a mortgage and only paid 18% of the price outright, a sum of around $8m if the reported purchase price of $46m is correct,

"Our family home in Geneva is our primary residence," she says. "We sold all real estate in Uzbekistan, leaving only an apartment in Tashkent where we stay with the children when we go to Uzbekistan."

Those trips back home are rare, only two or three times a year.

And given how far the president's youngest daughter has gone in distancing herself from her family and her country's image, they may become even rarer in the future.

Johannes Dell, Jenny Norton and BBC Uzbek reporters contributed to this piece.

- Published27 November 2012

- Published19 May 2011