Forced to fish: Slavery on Thailand's trawlers

- Published

Human Rights Watch says the use of forced labour on the boats is "systematic" and "pervasive"

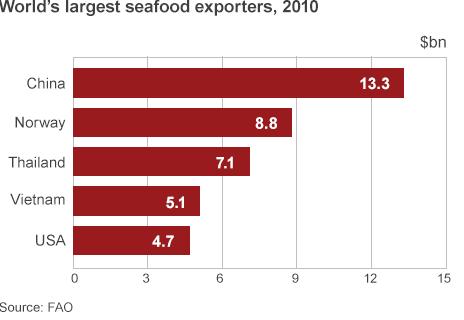

Thailand is the third largest exporter of seafood in the world, supplying supermarkets in Europe and America, but it's accused of crewing fishing boats with Burmese and Cambodian men who've been sold and forced to work as slaves.

Military music is pumping out into the tropical sunshine. In front of us are some 100 police officers standing in rows, and two heavily armed SWAT teams standing at attention. General Chatchawal Suksomjit, deputy chief of police, is walking down the lines, shaking hands, nodding and saluting.

With his dark glasses, slicked-back hair and shiny grey uniform he oozes importance.

He ushers us on to some waiting police boats and out into the waters of the Malacca Straits, along the border with Malaysia.

The general is head of a new committee set up to deal with the trafficking of men into the fishing business - an industry he describes as "dirty, dangerous and difficult".

Human rights groups claim the Thai fishing fleet is much worse than this. Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch, who wrote a report on it, external for the International Organization for Migration says the use of forced labour is "systematic" and "pervasive".

"The biggest problem we've seen is that if people can't work, people aren't useful on board, they can be killed and thrown overboard," he says. "It doesn't happen on every boat but it does happen enough to raise serious questions about the lawlessness in this industry."

General Chatchawal Suksomjit, on patrol in the Malacca Straits

There is also a recruitment crisis. By the Ministry of Labour's count, fishing boats in Thailand are short of 50,000 men. One captain at the port of Chonburi says they are desperate.

"Because Thai fishing is difficult, some people we have to force on to the boat," he says.

Many boat owners and captains rely on brokers to recruit their workers, but the brokers are often unscrupulous, tricking young men from neighbouring countries into a job from which there is no escape.

As the police boats charge out towards the border with Malaysia, we approach four battered fishing boats. The SWAT teams surge on to the deck of the first boat, but meet no resistance.

"The focus of the mission today is to find trafficked and forced labour," announces the general in Thai, before ordering the mainly Burmese crew down on to the deck. The crew have holes in their shirts or no shirts at all. Most are barefoot. We slide around on the nets, scales and fish guts on the deck.

When I talk in Burmese they speak quietly, glancing nervously at the captain and the crew master.

One group say they didn't know they were coming on to a boat when they left Rakhine State in the west of Burma, or Myanmar as it is also known. They owe a broker $750 (£450) for bringing them here. One man glances out from under a mop of salt-soaked hair. "It's been seven months," he says. He still hasn't been paid.

With my basic Burmese and the crew's reluctance to talk, it's hard to assess the situation but brokers, deception and debt often go hand-in-hand with forced labour.

Typically an illegal worker from Cambodia or Burma meets a broker and is offered a factory job. He accepts and finds himself passed from one broker to another, taken to a port and put on a fishing boat. The victim is then told he owes a lot of money.

It's a well-sprung trap. If he escapes, then as an undocumented migrant the police will arrest and deport him. One Cambodian man I spoke to was trapped for three years on a boat without any wages, while he "paid off his debt". He was never told how much he owed.

The general and his team cannot talk directly to the Burmese-speaking crew because they haven't brought a translator so determining whether the men are trafficked is not possible. After 20 minutes the general ushers us off the boat.

"Wouldn't it make your job easier to have a translator?" I ask. He replies that usually they rely on someone on board who can speak Burmese, such as the crew master. However, it's often the crew master who is accused of the worst cases of abuse and violence.

"How do you know there was no forced labour or trafficking here?" I ask.

"From what we saw, there was no lock-up or detention room," he says. "We saw no signs of harm on their bodies or in their facial expressions. By looking into their faces and their eyes they didn't look like they had been forced to work."

It didn't seem like a foolproof system.

When the authorities do rescue trafficked men they often end up in a government-run detention centre on the outskirts of Bangkok.

Ken is one of these men. He explains that he was promised a good job in a factory but was forced on to a tiny boat in the open sea where he fished 20 hours a day, seven days a week. When he talks, his rough fingers run over the word L.O.V.E, which is clumsily tattooed across his knuckles. The broker said Ken owed a lot of money for being found a job and taken to the port. Months passed but Ken, like so many others, was never paid.

"People said, anyone who tried to escape had their legs broken, their hands broken or were even killed," he says.

Desperate to escape, Ken jumped ship and swam for six hours in the open sea, until he was picked up by a yacht and dropped off in the resort of Pattaya. Like many trafficked men, he felt ashamed to return home empty-handed so when the police found him and deported him, he crossed the border illegally again to find work in Thailand.

This time he was told there was a job for him in a pineapple canning factory, and he agreed. But there was no factory, just another boat and another insurmountable debt. Fortunately for him, other crew-members managed to smuggle a phone on board to call for help and he was rescued as part of a special operation by Thailand's Department of Special Investigations.

Puntrik Smiti, the Deputy Director General at the Ministry of Labour, admits that men like Ken are vulnerable. "There are some good fishing operators who are trying to improve the treatment of workers," she says. "The problem is there are small operators who are unregistered and don't want to come into the system."

Ken's boat arrives in port, after the crew phoned for help

Only one in six boats is registered, she says, and most of the workers are illegal. She also points out that existing labour laws are inadequate. In fact Thailand's Labour Protection Act exempts workers employed in the fishing industry, while other ministerial regulations exclude boats with a crew of less than 20, or those that travel outside Thai waters for more than a year.

Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch says it is on these long-haul boats that the worst abuses take place.

"If you're talking about a fish caught on a Thai boat that has gone overseas, that has gone to Malaysian waters, Indonesian waters or further afield, you're definitely talking about a fish tainted with forced labour," he says.

"If you're talking about a fish caught in Thai waters, the chances might be less. But there are much fewer fish caught that way. And now the major exporting is coming from the overseas catch."

The effect of local over-fishing is forcing Thai boats to go as far afield as Yemen to maintain an export business worth $7bn annually. Mother ships refuel boats far from shore and transfer crews, ice and fish at sea.

Ken has been learning to cut hair in the detention centre

Trapped at sea, workers cannot escape or complain about their conditions. The system also muddies the supply chain because fish are mixed at sea, and often again at the ports and processing plants, before being sold to larger companies for export. Max Tunon of the International Labour Organisation, who published a report on the industry, external in September, says it is "close to impossible" to disentangle Thailand's fish supply chains.

Consumer pressure may one day force the industry to make these supply chains more transparent. Mackerel, sardines and other Thai fish are bought by some Western supermarkets and restaurants, while household brands such as John West and Chicken of the Sea are both subsidiaries of the largest exporter of Thai seafood, the Thai Union Group.

For its part, the Thai Union Group says it only sources fish from boats that are properly registered, with crews that have proper working documents. A representative says the company works with its partners to "take meaningful steps to promote human rights" in all its business operations. Mackerel and sardines accounted for only 6% of its revenue in 2012. Tuna is caught by a different fleet of boats.

A few days later in Burma, we sit on the floor of a bamboo shack in Bago, 100km (60 miles) north of Rangoon. This is Ken's home. Although idyllic, the poverty is palpable.

Ken's parents haven't heard anything from their son, who is now 32, for four years.

His father is thin, with a gaunt face and red teeth from chewing betel nut. His mother is plumper and has a comb holding up her grey hair.

I show them a video of Ken. "That's him! That's my son," his mother cries in recognition.

She raises her hands to her face and weeps, while her husband places his hand close to hers.

"We didn't know anything," she says. "We heard nothing."

"I am so happy, so happy," Ken's father says, unable to tear his red-rimmed eyes from the screen.

It's hard to know just how many more families like Ken's are waiting for sons and husbands trapped at sea. With some vessels spending months or even years away, without being checked, the system encourages abuse.

Ultimately, as one fishing boat captain told us, if the Burma or Cambodian economies boom and there are jobs for men back home, the Thai fishing fleet will be in trouble.

This could also force the industry to change its ways, quite aside from any consumer pressure. For now though, the flow of men trafficked into slavery on fishing boats continues.