US marijuana laws: Will records be wiped clean?

- Published

Moves across the US to legalise marijuana have been greeted by reformers as heralding the end of the "war on drugs". But what happens to people convicted of offences that no longer exist? And will the records of those arrested now be wiped clean?

This is a big year for American pot smokers. Business has been brisk at shops in Colorado where, for the first time, people can buy marijuana to smoke purely for pleasure. Stores in Washington state are set to open in a few months and others may follow, as authorities eye a new source of tax dollars from a policy that now has broad popular support, external.

Yet as the momentum for reform has gathered pace, one issue has largely been brushed aside - the fate of those arrested in the past.

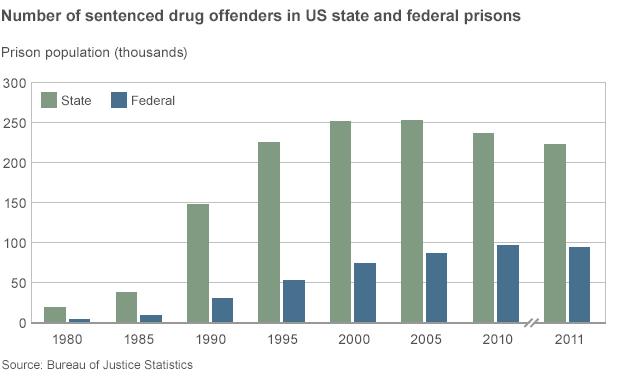

Every year for more than three decades, hundreds of thousands of marijuana-related arrests have been made across the US. According to activists, tens of thousands of those arrested for cultivating, selling and trafficking marijuana are currently incarcerated. At least 12 men are serving life-without-parole sentences in federal prisons for marijuana-only, non-violent offences.

In a petition for clemency, external for five of those men, Michael Kennedy, a New York lawyer and the director of High Times magazine, argued that their sentences had become "irreconcilable with our present sense of basic fairness and justice" because of changing attitudes towards harsh sentencing, and the change in "beliefs about the benefits of marijuana and its potential for harm".

Even those who were not convicted, merely arrested for possessing marijuana - in amounts now legal in Washington or Colorado - have a blot on their police record that can cause problems when they apply for jobs, housing, or student loans.

"Employers are routinely doing security checks and in many cases don't make any distinction between an arrest and a conviction," says Marc Mauer of the Sentencing Project, which campaigns for sentencing reform. "Any contact with the criminal justice system is essentially ruling people out in the eyes of many employers." He says this produces "profound racial disparities".

The number of arrests for marijuana possession in Colorado and Washington states is estimated at 450,000 from 1986-2010. Lawyers say people are just beginning to make inquiries about getting minor marijuana convictions overturned, or sealed from public view. Many may not have realised yet that such appeals are possible.

In Washington state, Democratic representative Joe Fitzgibbon sponsored a bill last year to make the process quicker and easier. The bill never made it beyond the committee stage, but he hopes it will fare better this year, once the "dust has settled" after legalisation.

"I thought it was the right opportunity to give people a chance for a fresh start," he says. "This would just be a policy decision by the legislature that this is a crime that the people don't believe should be a crime any more, and with that in mind there are thousands of people who deserve a second chance."

Some activists say they have steered clear of campaigning for law changes to apply retroactively, so as not to jeopardise reform. A legalisation initiative in Alaska in 2000 is seen to have failed at least in part because of provisions to grant an amnesty to those convicted in the past, and possibly compensate them.

"We have assiduously tried to stay away from this discussion," says Allen St Pierre, executive director of marijuana reform group Norml. "The morality from our point of view is clear, but political pragmatism makes it hard to embrace."

This reluctance is set against the backdrop of decades of rising rates of arrest and incarceration, external for drug offences, as "tough-on-crime" policies were adopted on the left and right.

In most countries, sentences would be reduced in the light of changes to the law, but not in the US. A report by the University of San Francisco found that it was one of just 22 countries, external, out of 193 surveyed, that did not provide for some type of automatic relief.

At the state level, some reform of harsh drug sentencing has already applied retroactively. And at a federal level there have been moves to provide retroactive relief in relation to one drug for which past sentencing is now considered to have been especially skewed - crack cocaine.

Based on fears about the dangers of crack that were later challenged, in 1986 Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which created a 100-1 sentencing ratio for between crack and powder cocaine. This meant that 500g of powder cocaine would be needed to trigger the same five-year mandatory-minimum sentence as 5g of crack cocaine, a form of the drug that was marketed in smaller quantities and therefore cheaper and more popular in poorer neighbourhoods.

It produced an "especially stark racial disparity", says Mary Price of Families against Mandatory Minimums, a campaign group.

"It was absolutely devastating to African-American communities," she says. There was "a generation of kids who went to prison for a long time, and some of them are still serving those sentences".

The harsh sentencing regime for crack has twice been reformed, first under new guidelines from the US Sentencing Commission in 2007 and again under the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.

Those changes have shortened by several years prison terms for thousands of people whose sentences exceeded the mandatory minimum.

Stephanie Nodd, a 46-year-old from Mobile Alabama, was one of those to benefit when she was released early in 2011.

In 1990, she had been sentenced to 30 years for her role in helping a crack cocaine dealer set up his business.

"I had four kids and I was carrying one kid into prison," she says. "It felt like my life was over and I didn't really believe that I got 30 years my first time in prison, getting in trouble on hearsay testimony."

While she was not caught with any drugs, she says she had a roommate who had been arrested with nearly 500kg (1,100lbs) of powder cocaine and was sentenced to 11 years - less than half her sentence.

Reforms of mandatory-minimum sentences for crack cocaine have not been made retroactive, but that would change under a bill currently up for discussion in the Senate, the Smarter Sentencing Act.

The bill would reduce mandatory-minimum sentences for all drug offenders going forward. It would also provide retroactive relief for an estimated 8,800 crack offenders, with an average reduction of about four-and-a-half years.

In December, President Barack Obama signalled his support by commuting the sentences of eight people convicted for crack cocaine offences, referring to "a disparity in the law that is now recognised as unjust".

That followed moves by Attorney General Eric Holder to send fewer people to prison for minor drug offences, and to limit the number of mandatory-minimum sentences.

Amid growing concern about the cost of keeping people in America's overcrowded prisons, drug sentencing reform is an issue that is suddenly generating keen bipartisan interest, says Mary Price.

"It's extraordinary, we have conservatives just flocking to this issue. I think that there's been - particularly among conservatives who've not always been supportive - a real recognition that we are spending our taxpayer dollars quite unwisely."

Todd Clear, a sentencing expert and Provost of Rutgers University in Newark, says piecemeal initiatives can help reduce arrests and sentences, but he isn't expecting deep legal change. As he puts it: "There's not much win there for a politician."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external