World War One: How did 12 million letters a week reach soldiers?

- Published

During World War One up to 12 million letters a week were delivered to soldiers, many on the front line. The wartime post was a remarkable operation, writes ex-postman and former Home Secretary Alan Johnson.

When a soldier on the Western Front wrote to a London newspaper in 1915 saying he was lonely and would appreciate receiving some mail the response was immediate.

The newspaper published his name and regiment and within weeks he'd received 3,000 letters, 98 large parcels and three mailbags full of smaller packages.

Had that soldier had the time to respond to every letter he could have done. Wherever he was fighting, his reply would have been delivered back to Britain within a day or two of posting.

How the General Post Office (GPO) maintained such an efficient postal service to soldiers and sailors during World War One is a story of remarkable ingenuity and amazing courage.

The imperative was clear from the start. Ever since the establishment of the Penny Post in 1840, the ability to communicate by letter reliably and cheaply had become a public expectation.

For fighting soldiers it was essential to morale and the British Army knew that. It considered delivering letters to the front as important as delivering rations and ammunition.

The Boer War of 1899 had established an expectation among soldiers that they would be able to stay in touch with those at home but the logistics of doing so in WW1 provided a challenge on an unprecedented scale.

The GPO was already a huge operation before war broke out in 1914. It employed over 250,000 people and had a revenue of £32m, making it the biggest economic enterprise in Britain and the largest single employer of labour in the world, according to the British Postal Museum & Archive (BPMA).

But at its peak during the war it was dealing with an extra 12 million letters and a million parcels being sent to soldiers each week.

Mail was sorted at field post offices

I became a postman in what was still the GPO almost exactly 50 years after the end of WW1. The way that mail was collected, sorted, despatched, received and delivered had changed very little. There was no mechanisation beyond a stamping machine to date-stamp letters. All sorting was done by hand. Mail was transported in sacks, the dust from which lodged in the throat and eyes and formed "tide marks" around the shirt collar.

The youngest of the men who'd survived WW1 were just reaching retirement age when I started work in 1965 aged 15. By the time I became a postman at Barnes in London three years later the men who'd fought in World War Two were in their 40s. Those who'd served in the same regiment gravitated towards the same canteen table. One in every three recruits into the GPO between the wars was an ex-servicemen moving from one uniformed occupation to another.

The terminology was militaristic and is to this day. Postmen didn't go to work, they went "on duty". We didn't take holidays, we took "annual leave". We weren't in a job, we were in a "service".

What characterised the GPO was a pride in our ability to move millions of letters from anywhere to anywhere, safely and quickly.

This pride must have burned even fiercer in the men of the Royal Engineers (Postal Section) or REPS as it was universally known. This was a part-time reserve unit in peacetime made up of GPO men who'd had a smattering of military training.

This unit of postal workers was immediately subsumed into the Army when WW1 broke out, but the Army was only in nominal command. This operation was controlled by the GPO. Even questions in Parliament about forces mail were answered by the Postmaster General rather than the War Minister.

Mail was taken from French ports by trains

At the outbreak of war the unit almost immediately created a sorting office in London's Regent's Park - a gigantic wooden hut covering several acres. Called the Home Depot, it employed 2,500 staff, mainly women, to sort post.

Outward mail was sorted by military unit. Each morning bosses would be informed by Whitehall of the latest movements of ships and battalions so each item of mail could be dispatched to the right place.

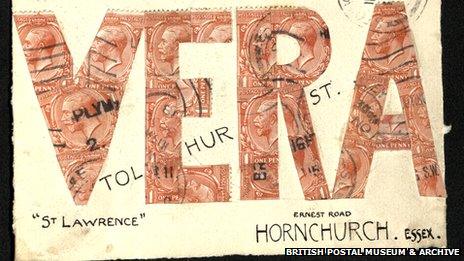

Some letters were addressed creatively

On its outward journey to the Western Front, a fleet of three-tonne army lorries would take the mail to Folkestone or Southampton where ships would shuttle it across to Army Postal Service (APS) depots in Le Havre, Boulogne and Calais.

Trains ran back and forth across Picardy under cover of darkness dropping some mail off along the route and unloading the rest at railheads where special REPS lorries took them to the "refilling points" for divisional supplies.

Regimental post orderlies would sort the mail at the roadside and carts would be wheeled to the front line to deliver it to individual soldiers. The objective was to hand out letters from home with the evening meal. It's said that no matter how tired and hungry the soldiers were, they always read the letter before eating the food.

Letters back were collected from the men from field post offices. These were equipped as comprehensively as a village sub-office, according to Masters of the Post: The Authorized History of the Royal Mail by Duncan Campbell Smith. Men could even buy War Savings Certificates there exactly as the population did back home. The mail was date-stamped with the field postmark and sent to the base post office for its journey home.

At the beginning of the war every letter home was opened and read by a junior officer. It was then opened and read again at the Home Depot to ensure that it contained no classified information about troop movements or casualties.

Eventually men could opt for an "Honour Envelope" which meant the letter would only be read in London, saving the embarrassment of having their deeply personal endearments read by a censor who they knew.

At its peak this incredible operation delivered over 12 million letters a week and one million parcels.

Wherever armed forces were engaged, REPS would follow, delivering to ships of the Royal Navy anywhere in the world and to soldiers away from the fixed positions of the Western Front.

In Gallipoli more unopened letters from those killed in action were being passed back from the front than letters going forward. The GPO always ensured that returned letters didn't arrive before the official telegram telling the family that their son was dead. There were 30,000 unopened letters every day.

Those postal workers who went to war were probably glad to be handling letters and parcels rather than rifles and bayonets, but their truly magnificent work was as important to the war effort as the weapons.

Indeed mail exchanged between soldiers and loved ones was a weapon. Those who wielded it made a huge contribution to the outcome of the war.

Find out more from Alan Johnson on why the humble letter was one of the most powerful weapons of WW1 and Frank Gardiner on why journalists were threatened with execution during WW1.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external