Calcium, building block for the world

- Published

It's the fifth most abundant element on Earth - and the world's building block. Do we fully appreciate the value of calcium?

Most of us are familiar with the idea that our bodies need calcium. I remember being told to drink up my milk because the calcium in it would make my bones strong.

And calcium is indeed the key element in our bones. In fact, it is the most abundant metal in the human body - and in those of most other animals too.

Many organisms use calcium to build the structures that house and support them - skeletons, egg shells, mollusc shells, coral reefs and the exoskeletons of krill and other marine organisms.

And calcium is also the key ingredient in man's most important structural material - cement.

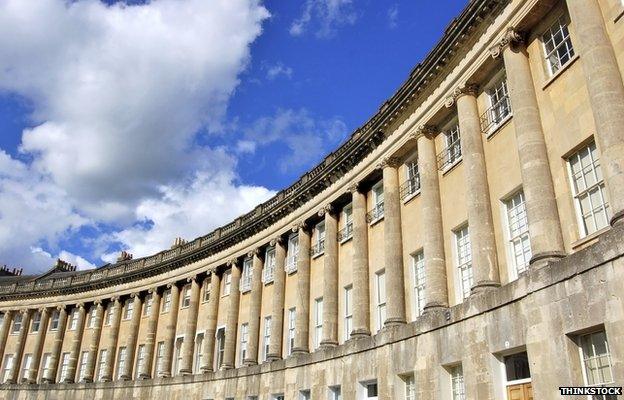

These days virtually all our architecture, all our great building and engineering projects start with calcium, because cement is the basis of the most widely used man-made substance on Earth - concrete.

Fortunately there's a lot of calcium about - the soft grey metal is the fifth most abundant element in the Earth's crust.

There is plenty dissolved in the sea. For millennia, marine organisms have been combining it with carbon dioxide they fix from the atmosphere to make shells of calcium carbonate.

When they die, their shells and skeletons sink down to the bottom of the sea and collect in great drifts. Over millions of years they have been compacted to form limestone, chalk and marble.

When you get the chance, take a close look at a piece of limestone. You'll probably see the tiny fossils of the ancient marine creatures of which it is composed.

Some 10% of all sedimentary rock is limestone, which is pretty extraordinary when you consider that it represents the concentrated bodily remains of living creatures.

So how do we get from limestone to concrete?

The key is extracting the calcium from limestone. It's a trick mankind learned very early on.

In principle the process is pretty simple - you just need to heat limestone up.

What you do is place your limestone - calcium carbonate - in a fire where the temperatures are high enough to drive out the carbon atoms as carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. That leaves you with calcium oxide - more commonly known as lime.

Lime is the basis of most cements - the glue that hold rocks and particles of sand together to make concrete.

Recent archaeological discoveries show some prehistoric people created concrete, even before they'd discovered the first metals.

Over the last two decades, a German archaeologist working in Turkey has uncovered what he believes is the world's first temple. It is a complex of carved stones erected about 11,000 years ago - 6,000 years before Stonehenge.

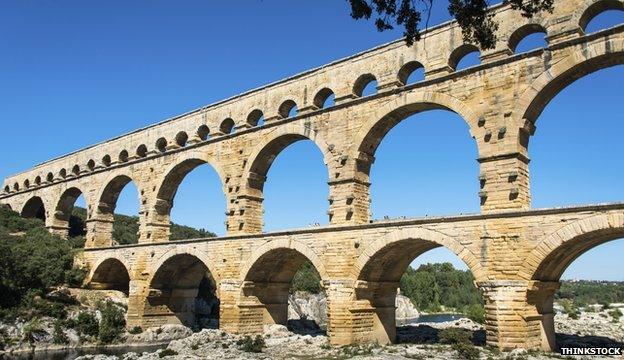

An early "concrete" was used on the Pont du Gard, constructed out of soft yellow limestone blocks

The site is called Gobekli Tepe - Pot-bellied Hill in Turkish - and features floors made of very early cements.

The technology was refined over the millennia. Two magnificent Roman buildings, the Pantheon and the Pont du Gard at Nimes, showed the potential of concrete.

They used it to enclose space with an unsupported dome, and to bridge considerable spans without reinforcement.

Nevertheless, these early concretes remained brittle and weak, which is why most buildings continued to be made of stone and brick.

The breakthrough came in the 1840s.

On a rainy February afternoon I went to see the site of this momentous advance. It could hardly be less cherished.

I had an expert guide in Edwin Trout, the chief archivist of the Concrete Society. We met outside WE Roberts' cardboard box factory on the banks of the Thames Estuary in Kent. Our destination lay deep within the factory complex.

We were led down an alleyway between two big buildings and in through a low door.

We had to duck under a cardboard corrugating machine - a surprisingly large contraption - and then through a door in the wall of the factory.

Portland cement was created inside a bottle kiln

It opened out on to a small courtyard almost entirely taken up by a looming brick structure. It was hard to get a good view, because it was surrounded on all sides by the walls of the factory. Nevertheless, it was clear that Edwin was excited by what he was seeing.

"Portland cement was first developed at this site by a chap called William Aspdin," he told me.

The brick circular structure, he explained, is one of the earliest kilns used to produce this new cement, external.

It is known as a bottle kiln, because of its shape, and it was here that Aspdin experimented - burning the limestone by baking it with clay at the then unthinkable temperature of 1450C. The result was a solid amalgam of the two materials known as "clinker".

Aspdin discovered that when this was ground to a fine powder, it produced an exceptionally powerful cement. And very soon, he got the perfect opportunity to test out his new product.

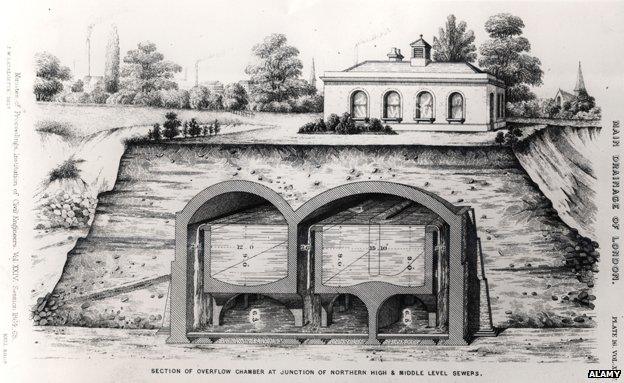

It came about because of what became known as "The Big Stink".

At the time, the Thames was essentially an open sewer. The booming population of London, the spread of industry, and the development of the flush toilet, all meant the volume of waste flowing into the river had risen dramatically.

In the hot summer of 1858, the stench became unbearable and there was a public outcry. The London boroughs finally agreed to commission the great network of new sewers that had been proposed by the visionary engineer Joseph Bazalgette.

The builders performed rigorous tests of the various cements on the market in order to choose the very best one for their vast scheme - the greatest public works project ever undertaken.

Portland cement, Edwin Trout tells me proudly, won easily. It was, he says, "stronger, more durable and - by that stage - more widely available too".

And it is a testament to the strength of the cement - and the power of calcium - that, 150 years later, Londoners are still using the sewers Bazalgette built to flush away their waste.

Indeed, the incredibly strong concrete Portland cement creates has transformed the building industry across the world - as the skyline of every major city shows.

The world produces about 3.5bn tonnes of cement a year. Given that cement is usually between 10% and 15% of the mix in concrete, that's enough cement to produce about four tonnes of concrete for every person on earth each year.

The problem is that creating all the cement for all that concrete is doubly polluting.

You need vast amounts of energy to get your kiln hot enough to bake all that limestone, and that usually means burning fossil fuels. And the limestone itself produces vast amounts of greenhouse gases, as all the carbon dioxide fixed by those ancient sea creatures is driven into the atmosphere.

Every ton of cement produces almost a ton of CO2. That's why the concrete industry is reckoned to be one of the most polluting on Earth, responsible for up to 5% of total CO2 emissions.

Listen to the latest from Business Daily or browse the podcast archive

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published8 November 2013

- Published18 November 2013

- Published23 November 2013