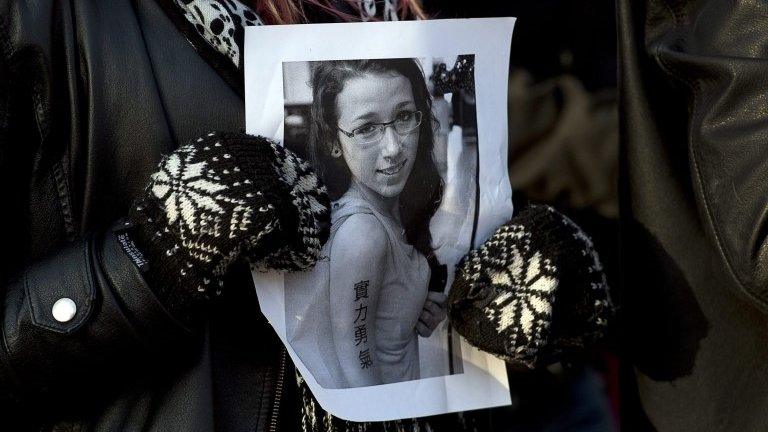

Rehtaeh Parsons: Father of cyberbully victim speaks out

- Published

The father of cyberbully victim Rehtaeh Parsons, speaks to the BBC about his grief a year after her death.

After a cyberbullying-related death, lawmakers in Canada's Nova Scotia province passed a comprehensive law aimed at cutting down on online abuse. But do the law and others like it address the underlying problems that lead to teenage cruelty?

Glen Canning is a man haunted by grief.

A year ago this month, his 17-year-old daughter Rehtaeh Parsons killed herself.

Now he is determined to speak about the circumstances of her death.

Rehtaeh was 15 when she was allegedly sexually assaulted by four boys. One of the boys took a photo of the incident, which spread through the school via the internet. Months of cyberbullying from her peers followed, culminating in her suicide.

"It's so frustrating to be a father with a daughter who has been raped," says Canning.

"You're Daddy. You're supposed to be the man in her life that helps and guides and saves her, and to have something like this happen and keep your composure without harming her further - it's a struggle," says Canning.

After her death, two boys were charged with possession and distribution of child pornography. The boys have pled not guilty, and the legal case is ongoing. But for many it was too little, too late.

The public outcry after Rehtaeh's suicide focused on police inaction after both the alleged assault and the subsequent harassment. Galvanised, legislators in Nova Scotia quickly designed a law to deal with cyberbullying.

The Cyber Safety Act allows victims to report cyberbullying to police, gain a protection order, and even sue the bully in court. It clarifies the role of school principals, and holds parents responsible for the actions of children under 18.

The Nova Scotia law has led to the creation of a first-of-its kind police unit dealing solely with cyberbullying complaints. The unit receives 25 calls every day, and since its inception in September, it has worked on 153 cases.

Veteran policeman Roger Merrick runs the unit, and says policing is 50% of what his officers do. The other half is speaking to students about cyberbulling prevention.

His officers strive to keep cases out of court and resolve complaints informally. In most cases, visiting the bully in question and serving him or her with a formal warning suffices.

In more extreme cases, investigators can ask a Supreme Court judge for a prevention order, forbidding any communication between the bully and the victim. A violation of that court order can lead to steep fines or jail.

The legislation also calls on parents to "responsibly" patrol their children's online activities, even though the parents may know less about social media than their children.

"We hold our kids' hands when we cross the road, we talk to them about stranger danger - and then we give them a device and leave them to it. We can no longer pretend we don't know about the dark side of the internet," says Mr Merrick

Nationally, the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act is being debated by the Canadian parliament, and could be passed in the next few weeks. The bill would make it a crime to share intimate images without the consent of the person in the image.

The bill was proposed in response to the deaths of both Rehtaeh Parsons and Amanda Todd, a British Columbia woman who killed herself after being bullied online and in person.

Critics worry the bill infringes on privacy rights.

And not everyone is in favour of the Nova Scotia law.

El Jones, an educator and Halifax's poet laureate, praises the law for its emphasis on consequences, but comes down hard on it for criminalising children, many of whom may have been bullied themselves.

"We need education," says Jones. "We can't just stop at a law and think that's going to take care of it for us."

She wants better sex education, in which boys are taught the importance of consent and girls to understand they are not obligated to agree to sex.

Rehtaeh's father spends much time thinking about boys these days.

"We created a monster, and that monster is our young men who have no idea how to treat women," Canning says. "They have no idea how to be a hero. They won't have a clue how to be a father."

It's because of their callousness, he says, that he no longer has a daughter to call him Dad.

Video produced by the BBC's Anna Bressanin

- Published8 January 2014

- Published11 February 2014

- Published9 August 2013