Do the public still trust the police?

- Published

A string of allegations have been levelled at the police in recent months, but has that eroded public trust, asks Simon Maybin.

Home Secretary Theresa May described as "profoundly disturbing" a report earlier this month that found undercover Scotland Yard officers tried to influence the family of the murdered black teenager Stephen Lawrence. She said that policing stood damaged by the findings.

The Metropolitan Police is also facing legal action brought by five women who say they were deceived into intimate relationships with undercover police. A police officer is in jail for lying about witnessing the "Plebgate" row involving MP Andrew Mitchell in Downing Street.

From the alleged Hillsborough police cover up, to the arrests of current and former police officers as part of the Met's Operation Elveden investigation into alleged payments to public officials in return for information, the institution has faced a raft of negative publicity recently.

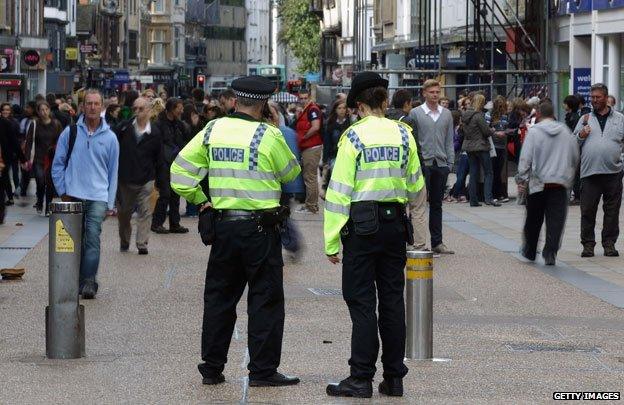

Public trust in the police has changed little in three decades

So do the public still trust their bobbies?

"We need to put what we see in the media in context," says Chief Superintendent Irene Curtis, president of the Police Superintendents Association of England and Wales. "There are over 120,000 police officers in England and Wales and - whilst I don't condone any of the conduct of officers who do bad things, who are corrupt - the vast majority of police officers and police staff out there do a fantastic job day in, day out."

Polling evidence suggests that whether or not public trust in police is as high as it should be, it hasn't been much affected by the recent bad news. Research company Ipsos MORI asked members of the public earlier this month, external if they would "generally trust the police to tell the truth or not". Sixty-five per cent said they would, compared with 31% who wouldn't. That rating is as high as trust in police has been since 1983, when Ipsos MORI - which has the longest-running series on trust, external compared with other polling firms - first asked the question.

The figure has varied remarkably little over the past 31 years, generally hovering in the low 60s. The lowest police trust rating was 58% in 2005.

Research firm YouGov has been asking people about trust in the police, external since 2003. It recorded a significant drop between that first poll and 2006, but in the past eight years the figures have been fairly steady. Earlier this month, YouGov found 67% of people said they trusted the police. The same poll asked if respondents' trust had been affected by recent reports about the Stephen Lawrence case - less than one in three said it had.

Another polling firm, ComRes, asked in October, external how likely people were to think a police officer speaking either on TV or in the street was telling the truth. Eighty two per cent answered either "very likely" or "fairly likely". A more recent poll, external for ComRes, published in January, found 50% of people agreed with the statement "I trust the police", compared with 26% who didn't - a similar ratio to the Ipsos MORI polling.

The consistency enjoyed by police in the Ipsos MORI series contrasts with, for example, trust in the clergy, which was 85% when the survey questions were first asked in 1983. The figure for 2013 was 66%, a drop of 19 percentage points over three decades.

Although police score more highly than politicians and journalists - who are trusted by just one in five - TV newsreaders, teachers and judges all have higher trust ratings. Doctors are the most trusted profession, with nine in 10 people putting their faith in them.

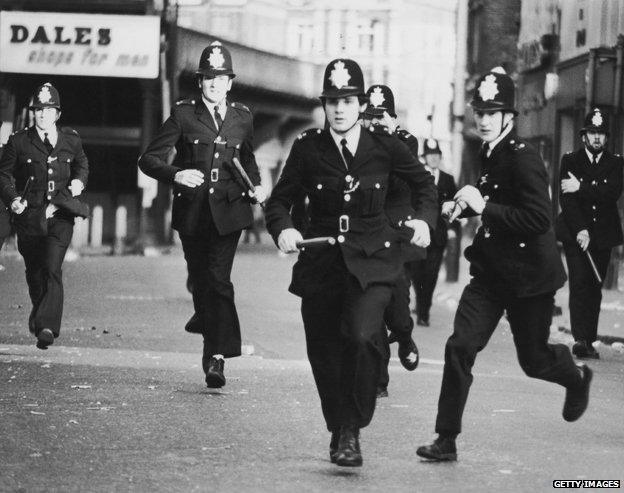

The Brixton riots in 1981 were the first serious riots of the 20th Century that the Met had to deal with

Looking further back, there does appear to have been a time when people were more trusting of police. The 1962 Royal Commission on The Police reported: "No less than 83% of those interviewed professed great respect for the police, 16% said they had mixed feelings, and only 1% said they had little or no respect."

There are various possible explanations for trust levels having fallen since the mid-20th Century. The 1970s and early 1980s were a time of social tensions that boiled over into violent clashes with the police during the miners' strikes and inner city riots. Broader cultural trends may also have played a part - for example British society becoming less deferential to authority in general.

But in the past 30 years, police in the UK have been held to higher standards and their actions more closely scrutinised, so it is perhaps surprising that trust didn't go above two in three - at least before the latest spate of negative reports.

Nonetheless, Irene Curtis is pleased that trust levels in the police haven't been adversely affected in recent months, and she has a theory about why. "The vast majority of the public actually base their confidence in policing on what happens in their local area and that local relationship with officers," she says. "So even though we've had lots of national issues in the media, it's what happens locally that's really important."

That can be a double-edged sword, though. "I'm not sure that the people who walk through my door would necessarily trust the police to solve their problems," says Chris Topping, a solicitor who specialises in actions against the police. "In fact, increasingly I would say that it's exactly the opposite, that often their experience of coming across a police officer is that it is an unfortunate and unpleasant one when previously they've perhaps trusted the police."

New inquests into the Hillsborough deaths are due to start soon

There is research, for example from the London School of Economics, external, backing up Topping's view. The more contact people have with the police, whether the contact is initiated by the police or by the member of the public, the less trust and confidence they are likely to have in them. The opposite is true for other public services like the NHS, where people have a more positive view after having contact.

Conservative MP Nick Herbert, who was policing minister from 2010 to 2012, says police are only belatedly realising that trust ratings of two-thirds are not enough, because that means a third of people don't trust them.

"The service has to hold up the mirror and say, actually there are some problems," says Herbert. "We have great strengths, we have great people, but we do have problems. Part of that is a cultural problem and we've got to address it."

New inquests into the deaths of 96 men, women and children at Hillsborough are due to start next week. The process of finding the truth about what happened and alleged attempts to cover it up is likely to open old wounds and create more negative headlines for the police.

Curtis says the best response for the police is to get on with doing the best job they can. "Every officer needs to understand that they're an ambassador for the service, that their responsibility is to go out there and build trust and confidence in every interaction that they have with members of the public."

The Policing Debate on Radio 4's Law In Action is broadcast on Tuesday 25 March at 16:00 GMT, or catch up on the BBC iPlayer.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external