The hidden meaning within your furniture

- Published

Furniture is often overlooked as a mundane feature of the home. But its resonance in our lives is much more profound, writes author Ian Sansom.

Furniture contains numerous traces of what we are and who we are and who we think we are.

Cupboards, for example, contain our past - as well as our regrets and secrets. Keys which fit no locks, pieces of paper with obsolete phone numbers and pin numbers written on them, stray playing cards, inexplicable plastic things and old French francs. Why we keep any of this stuff I do not know, except as something to hand on to our own children, to keep in cupboards of their own - our endless inheritance of waste.

Our wardrobes, meanwhile, suggest who we might have become, and where we might have gone. In 1908 E Nesbit published a story in Blackie's Children's Annual, titled The Aunt and Amabel. In the story, a young girl, Amabel, is punished by her aunt for cutting off the heads of flowers in the greenhouse. Furious, the aunt confines poor Amabel to the spare bedroom, where she discovers a book of railway timetables which list a destination called Whereyouwanttogoto.

"This was odd," writes Nesbit, "but the name of the station from which it started was still more extraordinary, for it was not Euston or Cannon Street or Marylebone. The name of the station was Bigwardrobeinspareroom." And so Amabel embarks on her adventure.

In 1948 CS Lewis wrote to a friend that he was attempting to write a children's book "in the tradition of E Nesbit". The children's book he wrote was, of course, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, published in 1950, and one of the Nesbit traditions he borrowed was the magic wardrobe. Lewis uses his wardrobe to enter an entirely different realm - his destination is the Celestial City.

Like wardrobes, beds act as transports for the imagination also. Writers in particular love to work on the horizontal. Milton's Paradise Lost was mostly written in bed. As was much of Winston Churchill's history of World War Two. Truman Capote claimed that he couldn't think properly unless he was lying down. He liked to start his day in bed with coffee and then move on to mint tea, to sherry and finally to martinis - his bed was a bar.

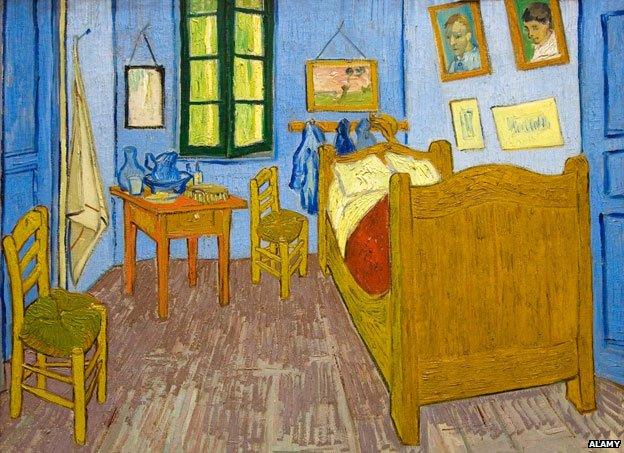

Furniture also has an emblematic and symbolic function - think of Van Gogh's famous paintings of two chairs, Gauguin's chair and his own, which vividly represent what he imagined to be the difference between him and his friend. Gauguin's chair is a dark brown-red, with generous curved arm-rests, its seat loaded with books and with a candle set upon it, erect and flickering - an image of warmth, wealth, contentment, learning, potency and power. Van Gogh's chair, on the other hand, is yellow, plain and rickety - it looks very much as though it has been made by someone who could do with a little more practice on their mortise and tenon joints. It is a simple man's chair - a poor man, but an honest man.

All furniture communicates meaning - it's unavoidable. It's what things do. A bed speaks of our inner lives, of the body and the soul. Our cupboards and cabinets imply secrets. Wardrobes suggest our dreams of other worlds. And tables invite company.

There are perhaps more kinds of tables than there are of any other type of furniture - kitchen tables, coffee tables, refectory tables, drafting tables, billiard tables, chess tables, table-tennis tables, communion tables, dressing tables, operating tables, library tables, bedside tables, night tables, and side- and end- and sofa tables.

There are innumerable uses for all these tables, but just one thing that unites them, apart from the obvious fact that they all have flat, horizontal surfaces - they are all gathering places, for both people and things. It is significant that the table is at the centre of religious practices - in Judaism, in the home, in Christianity, at the altar - and our language of course is replete with metaphors using tables as proverbial meeting places and negotiating platforms. We put a deal on the table. We drink someone under the table - and then we turn the tables on them. The table is the place where we interact with others - with family, friends, colleagues, rivals - and enemies.

The value of a table, like all pieces of furniture, lies in its history. We might make it, but furniture in turn makes us. It shapes us, defines us, and determines our everyday lives.

Novelist and academic Ian Sansom's week-long series of The Essay: Furniture: A Personal History of Movable Objects runs from Monday 7 April - Friday 11 April at 22.45 BST on BBC Radio 3.

Discover more on the history of the home and the rooms you use every day.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

Is there a piece of furniture which holds particular meaning for you?

Send a picture and tell the story behind the furniture using instructions below.