Cubans hungry for internet revolution on the Communist island

- Published

Cubans are impatient for freer access to the internet, the BBC's Sarah Rainsford reports from Havana

It's a month since Cuba's government started permitting people to have email on their mobile phones but the queues to sign up for the service are still enormous.

In one Havana street, some waited in the blazing sun for seven hours outside the door of the telecoms monopoly, Etecsa.

"It's cheaper than phone calls," Ana explains of the new service she is queuing for. Like many Cubans, she has family living abroad and wants to keep in touch.

"It's also because we want to progress a bit, and have the same as everyone else in the world," Ana adds.

But Cubans are still far from fully "connected". The new phone service is limited to email and does not include the internet.

There is often a long wait to sign up to get email on mobile phones

"It's like asking a child if he wants milk," Oscar snorts, when asked if he would like to get online too.

"You don't ask about something like that, you just give it."

Restricted

Cuba's Communist government has always maintained tight control of information. All local media are state-owned and no foreign newspapers are sold on the island.

The same has been true of the internet although restrictions were also due to an expensive link-up via satellite, with limited capacity.

Currently, some government officials and foreign residents are among the select few permitted full access at home and work.

Doctors and some academics have a limited intranet service that grants them a few hours email time a month as well as information specific to their profession.

Even that comes via a screeching dial-up modem: you can usually make coffee in the time it takes to open an email.

Costly connection

But three years ago, a high-speed fibre-optic cable arrived in eastern Cuba courtesy of Venezuela, and islanders began to dream of getting connected.

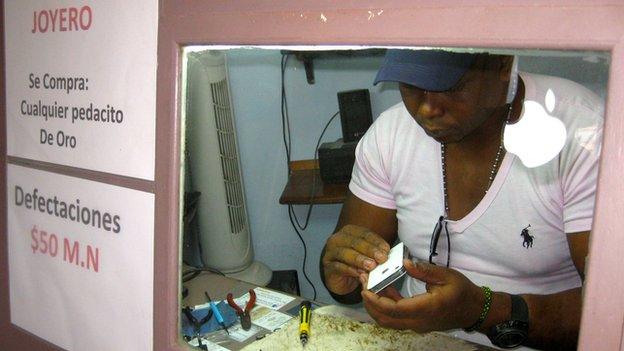

Smartphones, and shops repairing them, have become popular across Cuba

There are now some 300 public internet-access centres across the country, but they are expensive: one hour costs the equivalent of a week's wage for a state worker.

Still, some people are clearly finding the money - from private-sector jobs, the shadow economy, or family overseas.

"I use email, not the internet, because that's more expensive," explains student Yan Roja, as he logs on at one of the new centres.

Email costs the equivalent of $2.50 (£1.50) an hour; the internet is $4.50.

"This is much better than at my university, though. There's only intranet there and the keyboard was faded. This one's new, and it's much faster," Yan says.

"I only use it for email. I have to focus on what's most urgent," Sergio agrees, at a nearby terminal.

"I think the charge is excessive when people have so little," he says, explaining that he would read the news and books online if access were cheaper.

Catch-up

Cuba has clearly been weighing up the need to play technological catch-up against the potential political danger of widespread access to the internet.

Instructions on how to configure email on smartphones has been posted at the official shops

The authorities' concerns were underlined this month when details of a secretive US government programme emerged.

ZunZuneo created a local Twitter service for Cuba, allegedly aimed at prompting anti-government activity.

Even so, Cuban officials say that internet services will be expanded "as soon as possible", arguing that delays are due a lack of funding, not political will.

"The proof is the email service we've opened for phones, and there'll be new services with the internet," Carlos Porto from the communications ministry told the BBC, though he would not be pushed on a date.

'Underground network'

Until then, Cubans are doing what they have always done: getting round the restrictions.

Vivian - not her real name - pays $20 a month for 10 hours online, on the black market. That gets her the dial-up account details of an unknown foreign student on the island.

"Sometimes it's busy when I try to log on which means someone else is using it," Vivian explains, starting up the bootleg account in her living room.

She needs email to run her business, renting out private rooms to tourists. Even then, her time online is so limited that her brother in the US manages all the queries and only forwards Vivian the final results.

"It's sad because I'd like to search for information or download books online but it's very, very slow," she says. Still, she is grateful she at least has email now.

"The need is there, so there will always be interest in getting the service," - even illegally - Vivian reasons.

There is no data on how many people connect to this "underground" network. But there are other ways around the internet blockade.

The growing number of Cuban smartphone owners use unlicensed traders to transfer dozens of offline apps to their handsets for a few dollars.

Hungry for contents

You can buy 100 GB of films and popular TV series for around $3, copied straight to your hard drive, or fill up a flash disc with e-books and magazines.

"It's the only way people have to read this stuff," Jose Luis explains, scrolling through the titles he is offering, under the counter, at just one Cuban peso ($0.04) apiece - including Spain's El Economista and Cosmopolitan.

Smartphones give Cubans access to less revolutionary fare than the traditional book stands

It is Cuba's take on "samizdat" - the self-published literature once passed around the Soviet Union among dissidents. Here though, flash drives are more likely to be loaded with Hola! magazine than Solzhenitsyn.

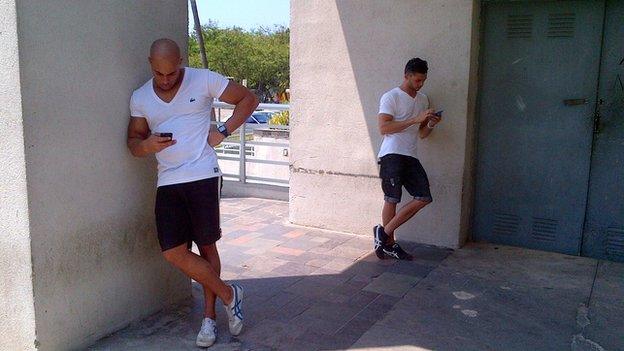

And sometimes, the internet-hungry Cuban gets lucky. Word will spread that a wi-fi network has been left open, without a password.

Word soon spreads If a free wi-fi network is detected somewhere,

It happened recently in Havana, quickly drawing a small crowd to the kerb outside who crouched under the palm trees and frantically tried to hook up their iPads and telephones.

"I just want to chat to friends abroad on email or Facebook," one man there explained, adding that official internet centres were too expensive to use often.

"This is very slow," he says, of the free guerrilla wi-fi. But until it is discovered and closed down, he shrugs, "at least it's something".

- Published31 May 2013

- Published24 January 2013

- Published5 October 2012