Chlorine: From toxic chemical to household cleaner

- Published

Few chemicals are as familiar as table salt. The white crystals are the most common food seasoning in the world and an essential part of the human diet.

Sodium chloride is chemically very stable - but split it into its constituent elements and you release the chemical equivalent of demons.

The process is brutal. Vast amounts of electricity are used to tear apart the sodium and chlorine atoms in salt molecules through the process of electrolysis. It happens at vast industrial sites known as chlor-alkali plants, the biggest of which can use as much electricity as a small country.

Which is why the price of both chlorine and sodium tend to track the price of electricity very closely.

It also explains why Industrial Chemicals Ltd's chlor-alkali plant in Thurrock, Essex, is right next to an electricity substation.

David Compton, ICL's chief chemist, shows me a huge mound of pure white salt. It comes, he tells me, from the rock salt deposits buried under Cheshire, in the north of England, a resource that was first mined by the Romans. And it's at least as pure, he says, as the salt you sprinkle on your dinner.

It is mixed with water in huge basins to make a concentrated brine, which is pumped into a big industrial barn that contains what looks like a giant chemistry set.

A series of huge tanks are connected by a web of pipes painted in different colours, all leading back to a big black tank. This is the business end of the process, the electrolyser.

It exploits an equivalence between chemistry and electricity that was first codified by Michael Faraday. Sodium and chlorine are both highly reactive - bring them into contact with each other and an electron passes between them, gluing them together to become salt. Reverse the process - by creating an enormous electrical current in the opposite direction - and you can split them apart again.

Inside the electrolyser, the brine is fed into a series of cells each separated by a membrane. Chlorine gas is produced at one electrode, and hydrogen gas - split off from the water molecules in the brine - at the other, leaving behind a solution of sodium hydroxide, also known as caustic soda.

Chlorine is named after the Greek word for "green"

Until fairly recently the process used mercury as one of the electrodes. This produced chlorine-free sodium hydroxide, but released tiny traces of mercury, which is very toxic, into the environment. So mercury cells are gradually being phased out around the world.

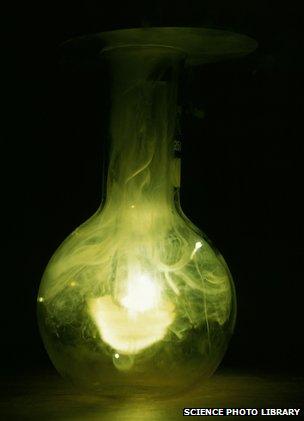

Inside ICL's laboratory, Andrea Sella, professor of chemistry at University College London, hands me a fragile-looking glass balloon. It is an evil-looking greenish-yellow colour.

"That's chlorine," says Professor Sella, with a wicked grin, "one of the most ferociously aggressive materials out there."

I grasp the bulb of lethal gas more carefully.

Andrea describes chlorine as aggressive because it is very reactive. That makes it extremely useful, but also very dangerous. It takes its name from its sickly colour - chloros is the Greek word for green.

As all chemists know, you need to be very careful with chlorine. Its reactivity makes it very toxic. If you inhale chlorine, it reacts with the water in your lungs, converting it into powerful acids. The effects can be horrific, as the World War One poet, Wilfred Owen, witnessed first-hand.

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

In his poem Dulce et Decorum Est, Owen describes the effects of the deadly chlorine gas used by both the German and British armies during World War I. It was particularly effective as a chemical weapon because it is heavier than air and, on still days, would collect in the trenches.

Gas-masked men of the British Machine Gun Corps during the first battle of the Somme

"Drowning" very accurately describes what happened to soldiers who were exposed to the gas. Their bodies responded to the irritation caused by the acid by filling their lungs with liquid. Many died from suffocation.

But while chlorine may have been put to some dastardly uses over the centuries, its reactivity has also been incredibly useful to humanity. It means chlorine is relatively easy to incorporate into other materials and often makes compounds more stable.

"That's because," says Andrea with relish, "chlorine hangs on like grim death to the atoms it bonds with."

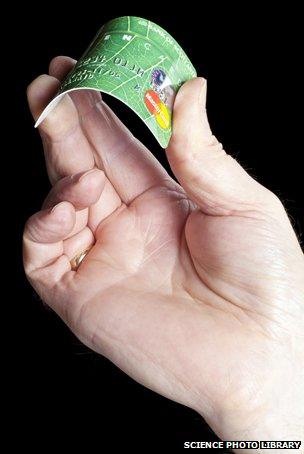

One of the best examples is polyvinylchloride, or PVC, which consumes a third of chlorine. This incredibly versatile and durable plastic celebrated its centenary last year. PVC crops up everywhere - packaging, signage, old-fashioned vinyl records, the leatherette effect of many car seats.

But it is the construction industry that is by far the biggest end-user of this plastic. Over 70% of PVC ends up in everything from drainpipes to vinyl floors, roofing products to double-glazed window-frames.

"We call it the construction polymer," says Mike Smith, chlorine market expert at the consultancy IHS.

"Chlorine also goes into construction in other forms," he adds. "Polyurethane, which is a great insulation material."

And that has the odd consequence that the demand for chlorine rises and falls in line with property booms and busts.

And because the supply of sodium is inextricably tied to that of chlorine, it has an even odder consequence. A collapse in the housing market - as Spain suffered in recent years - can make it more expensive to manufacture staple products like soap and paper, which rely on sodium.

But PVC is just one of chlorine's many industrial applications. Chlorine is one of the most versatile and widely used industrial chemicals.

"It is a real workhorse," says Mike Smith, adding that much of the chemical industry would be impossible without it.

Something like 15,000 different chlorine compounds are used in industry, external, including the vast majority of pharmaceuticals and agricultural chemicals.

Often chlorine is used during the production process and doesn't actually turn up in the final product. That's true of the production of two vital elements.

From a battered cardboard box Andrea produces a cylinder 15cm long and 3cm wide, encrusted with crystals of a beautiful silver-coloured metal. It is, he tells me, titanium.

Titanium is the basis of much of the paint industry. It is used in hi-tech alloys for aircraft and bicycles as well as in dental implants and chlorine is an indispensable part of the purification process.

Similarly the incredibly high-purity silicon essential for the production of computer chips and solar panels is only possible thanks to a process that uses chlorine.

But it was chlorine's cleansing power that led to the first commercial applications of the element. Its efficacy as a disinfectant was discovered thanks to an early 19th Century effort to clean up the gut factories of Paris.

The "boyauderies" processed animal intestines to make, among other things, strings for musical instruments. A French chemist and pharmacist called Antoine-Germain Labarraque discovered that newly-discovered chlorinated bleaching solutions not only got rid of the smell of putrefaction but actually slowed down the putrefaction process itself.

Within a few decades chlorine compounds were being used to disinfect everything from hospitals to cattle sheds as well as to treat infected wounds in patients. Chlorine is credited with deodorising the Latin Quarter of Paris, until then infamous for its terrible stench.

The early advocates of chlorine did not know how chlorine worked, they just knew that it helped clear the "miasmas" thought to spread contagion.

It would be half a century before the microbes that chlorine destroys would be identified.

Chlorine is used around the world to treat water to ensure it is safe to drink.

It is the basis of many disinfectants and a key ingredient of the bleach you use to clean surfaces in your home and to purge any microbes from your toilet bowl.

It is also used to keep swimming pools free of bacteria, hence the distinctive smell.

But here's something you probably didn't know, and if you are a regular swimmer, may not wish to know. That smell isn't chlorine, at least not the element. It is actually a chlorine compound called chloramine, which is created when chlorine combines with organic substances in the water.

So what are those organic substances? We are talking about sweat and urine.

So if you've ever noticed that the "chlorine" smell is stronger when the pool is full of kids, well now you know why.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external

- Published8 November 2013

- Published18 November 2013

- Published23 November 2013