Will firing squads make a comeback in the US?

- Published

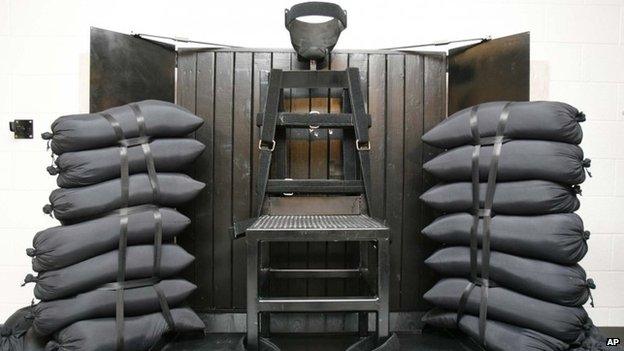

The seldom-used firing squad chamber in Utah State Prison

As the drugs used in lethal injections become scarce amid an EU embargo, some US politicians are suggesting alternative methods to execute criminals. Could they turn to an option seldom used since the end of the Civil War - the firing squad?

Death by firing squad is rare in the United States - the last execution using this method was just four years ago in Utah. Since then, more than 150 people have been put to death by lethal injection.

Convicted murderer Ronnie Lee Gardner chose the firing squad as his method of execution.

On 17 June 2010 his arms, legs and head were strapped to a metal chair and four bullets - from five sharpshooters, one whose gun was loaded with blanks - ripped through a target pinned over his heart.

It was a swift execution, but critics called it barbaric, external.

But a botched lethal injection in Oklahoma last month has brought back talk of firing squads.

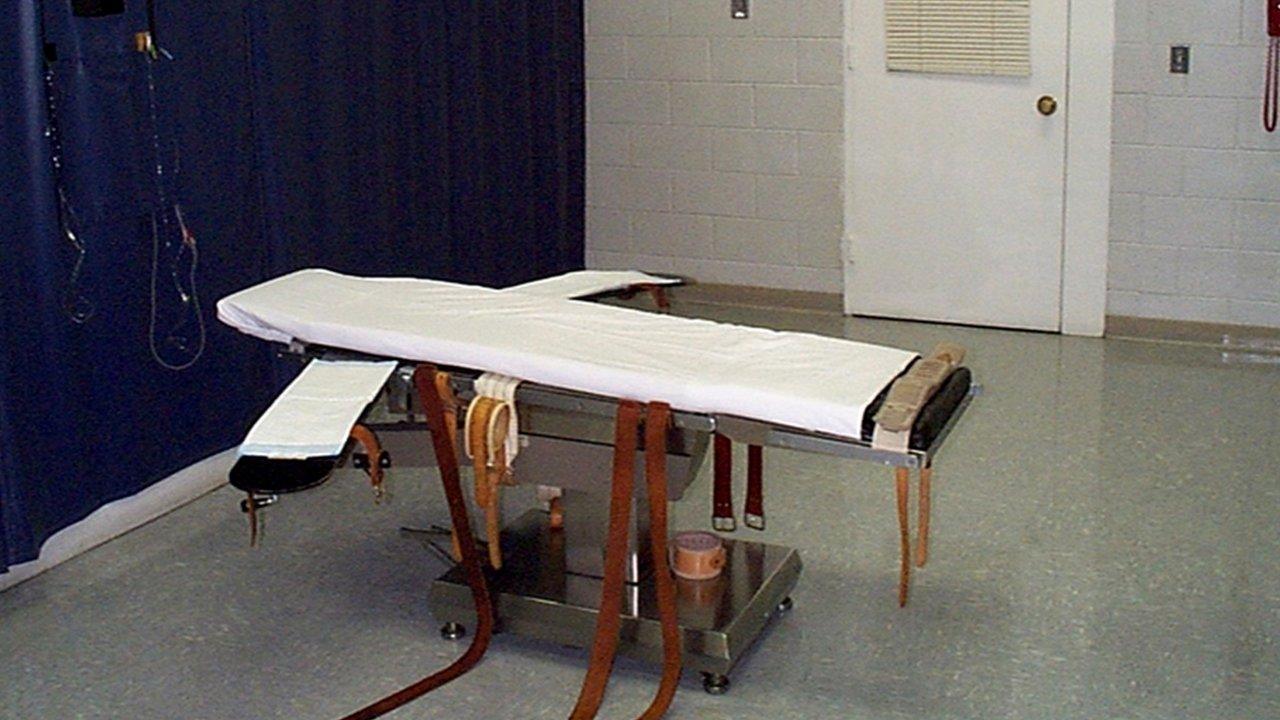

Convicted rapist and murderer Clayton Lockett was strapped to a gurney. The first drug in the three-drug lethal injection cocktail was supposed to sedate him, but spectators were stunned when Lockett raised his head and started moaning and writhing.

Lockett died of a heart attack 43 minutes after officials stopped administering the drugs.

Proponents of capital punishment say Lockett got what he deserved and suffered less than his victims. But opponents say it was clearly a case of "cruel and unusual" punishment, which is proscribed by the US constitution.

The EU has implemented strict controls on exports of certain drugs to assure they are not used in executions in the US and elsewhere. This has caused a shortage of the drugs previously used in executions. States have turned to less-precise compounding pharmacies to create new drug cocktails, the details about which are closely guarded secrets in some states.

Anti-death penalty activists who argue these drugs could cause a botched execution point to cases like Dennis McGuire, an Ohio inmate who took 25 minutes to die, and another who said he felt his body "burning" as the drugs coursed through his veins.

Now some lawmakers are proposing a return to other methods of execution as a way to continue the death penalty.

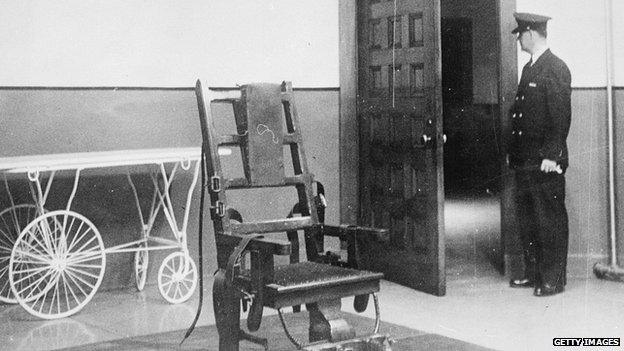

Virginia legislators have tried to reinstate the electric chair - above, a chair photographed in 1951

"I realize this may sound harsh," Oklahoma Representative Mike Christian told local reporters after Lockett's death, "but as a father and former lawman, I really don't care if it's by lethal injection, by the electric chair, firing squad, hanging, the guillotine or being fed to the lions."

In Oklahoma it is legal to use firing squads as a back-up method of execution, but only should lethal injections be declared unconstitutional by the state or federal courts. Executions in that state are currently on hold as officials evaluate what went wrong in Lockett's case.

In Missouri a bill is being considered to allow firing squads.

"This isn't an attempt to time-warp back into the 1850s or the wild, wild West or anything like that," Missouri state Representative Rick Brattin told reporters earlier this year. "It's just that I foresee a problem, and I'm trying to come up with a solution that will be the most humane yet most economical for our state."

A similar bill recently was rejected by Wyoming's state legislators. The gas chamber is available in Wyoming as a back-up method, though the state does not have any gas chambers. Virginia legislators tried to reinstate the electric chair should lethal injection drugs be unavailable, but the bill stalled in the Senate.

There have only been three civilian firing-squad deaths in the United States since the end of the Civil War - all of them in Utah. The state outlawed that method in 2004, but it remains an option to a handful of people remaining on death row who were sentenced before the ban became law.

After a lethal injection in Oklahoma went bad, officials shut a curtain to block spectators' view

Richard Dieter, the executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center, says talk of firing squads and electric chairs is more political theatre than real policy suggestion.

"These are threats. The core is saying, 'If you interfere, if you make us reveal the sources of drugs, or make us obtain drugs from other places, then we may have to go back to other means,'" Dieter says. "It's a warning shot."

Dieter thinks it is unlikely states will return to firing squads or other methods of executions.

"If they did the public would be outraged - there would be smoke and blood and smells and people would be sick watching it," Dieter says.

Franklin Zimring, a criminal justice scholar at the University of California-Berkeley, believes states would struggle to staff firing squads.

"It carries connotations of enormous power, getting lots of people to shoot you. We have a hell of a time getting one or two people to press a button [to administer the drugs], so getting eight of them to shoot at the same time? It becomes a matter of state secrecy who done it," he says.

"Very few families want to raise their first born to be an executioner."

The next execution in the US is scheduled for 21 May in Missouri.

- Published15 November 2013

- Published8 August 2012

- Published4 April 2014